Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Volume 63(2); 2025 > Article

-

Review

Advancements in dengue vaccines: A historical overview and pro-spects for following next-generation candidates - Kai Yan1, Lingjing Mao2,3, Jiaming Lan2,*, Zhongdang Xiao1,*

-

Journal of Microbiology 2025;63(2):e2410018.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2410018

Published online: February 27, 2025

1State Key Laboratory of Bioelectronics, School of Biological Science and Medical Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, P. R. China

2CAS Key Laboratory of Molecular Virology & Immunology, Shanghai Institute of Immunity and Infection Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, P. R. China

3University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, P. R. China

- *Correspondence Jiaming Lan jmlan@ips.ac.cn Zhongdang Xiao zdxiao@seu.edu.cn

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

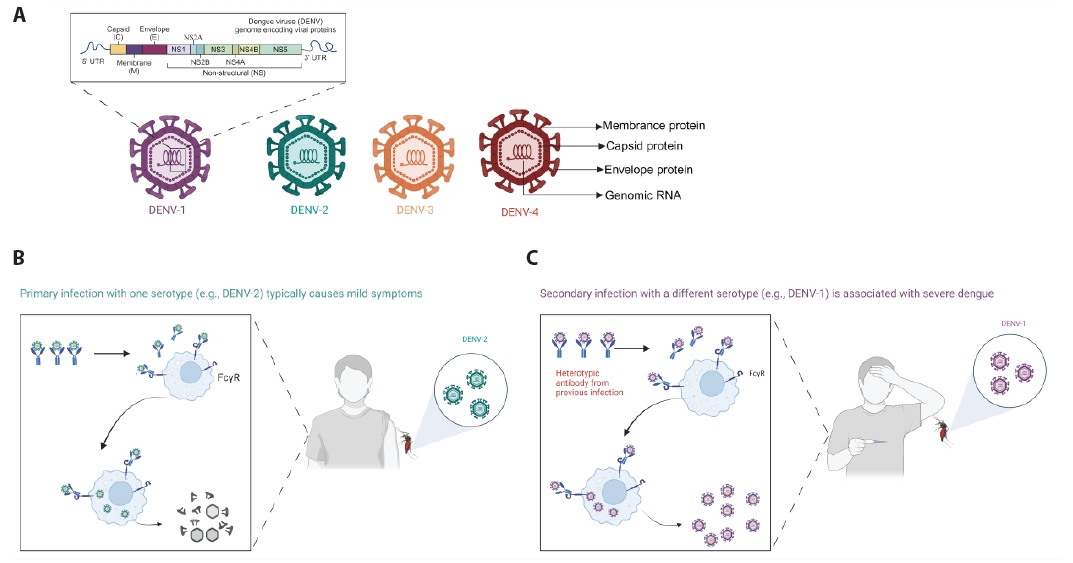

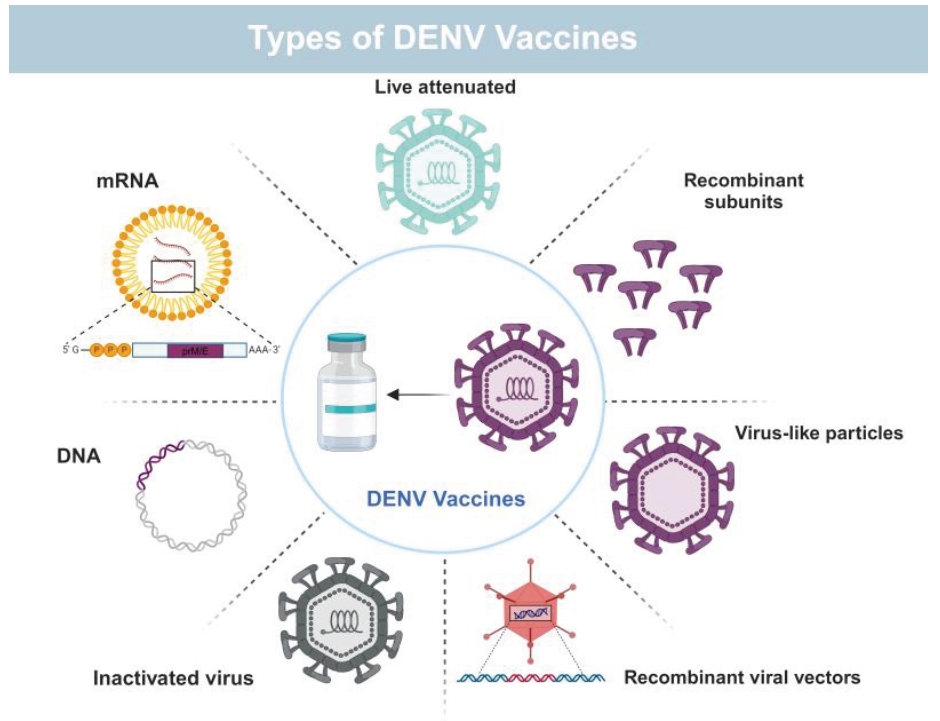

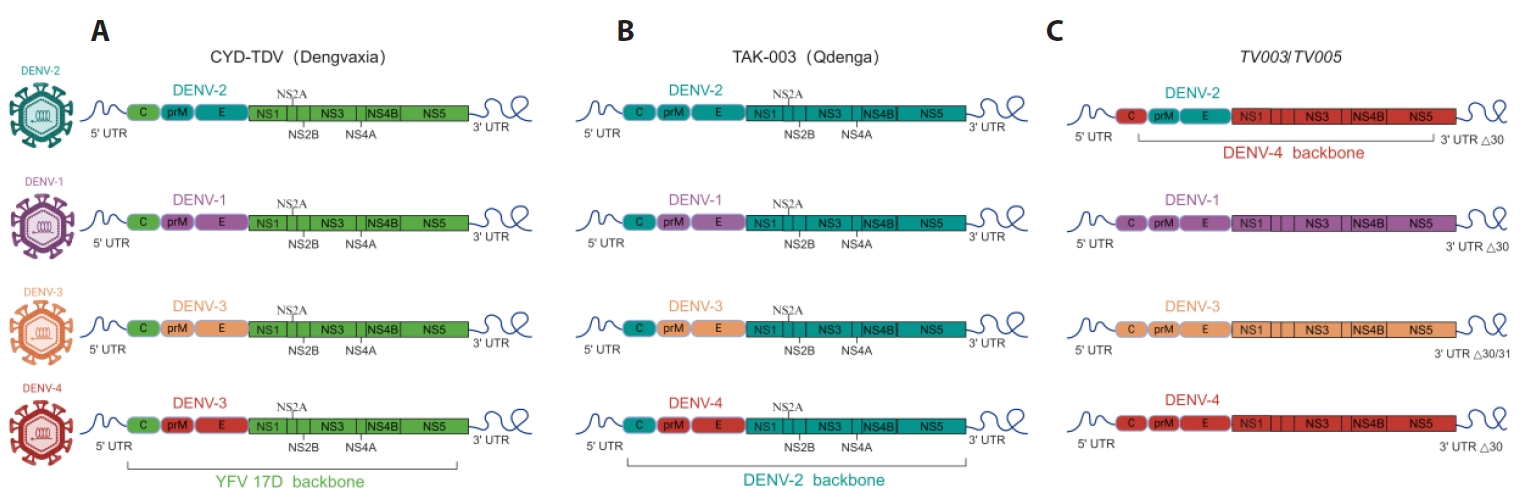

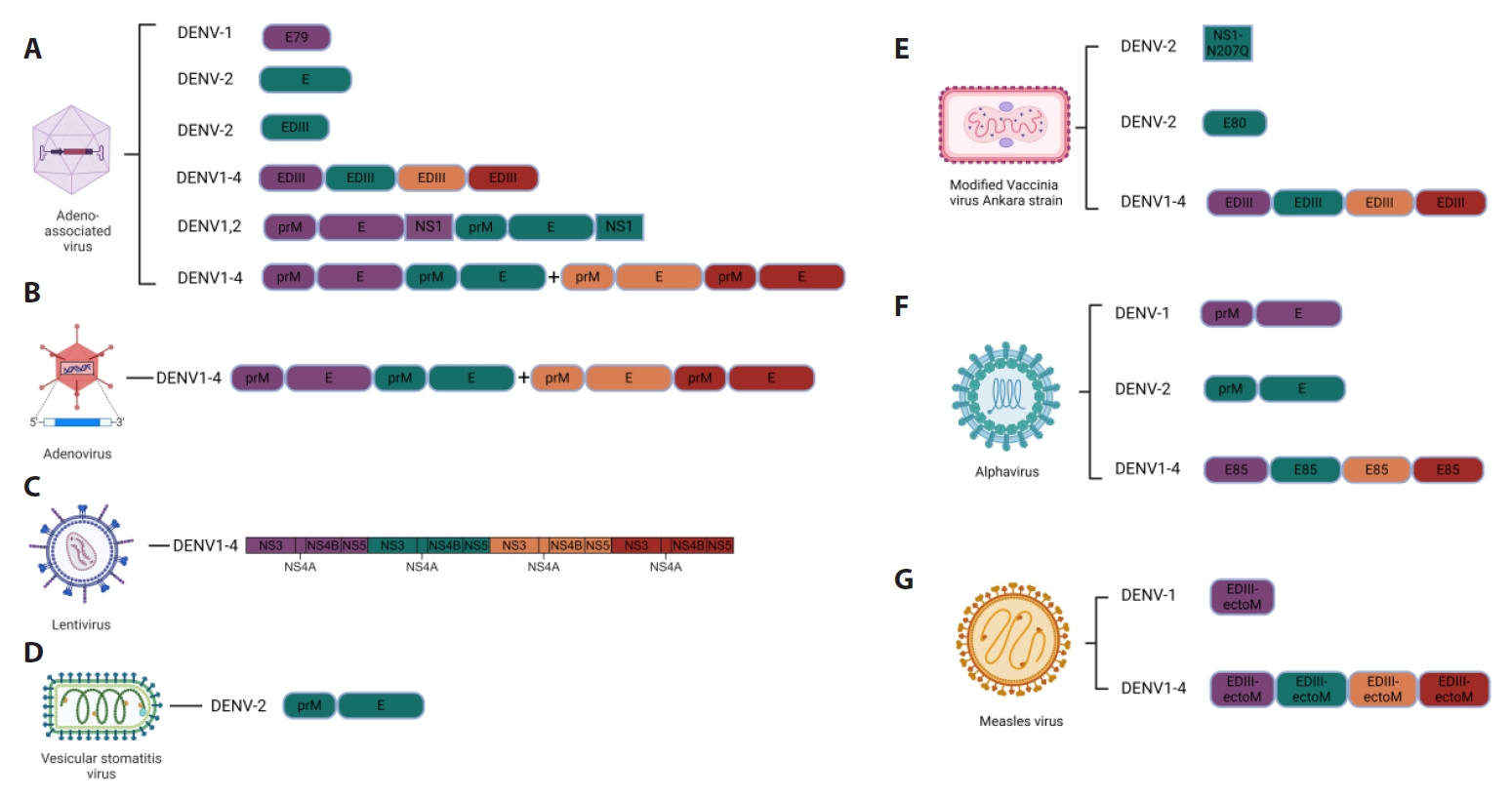

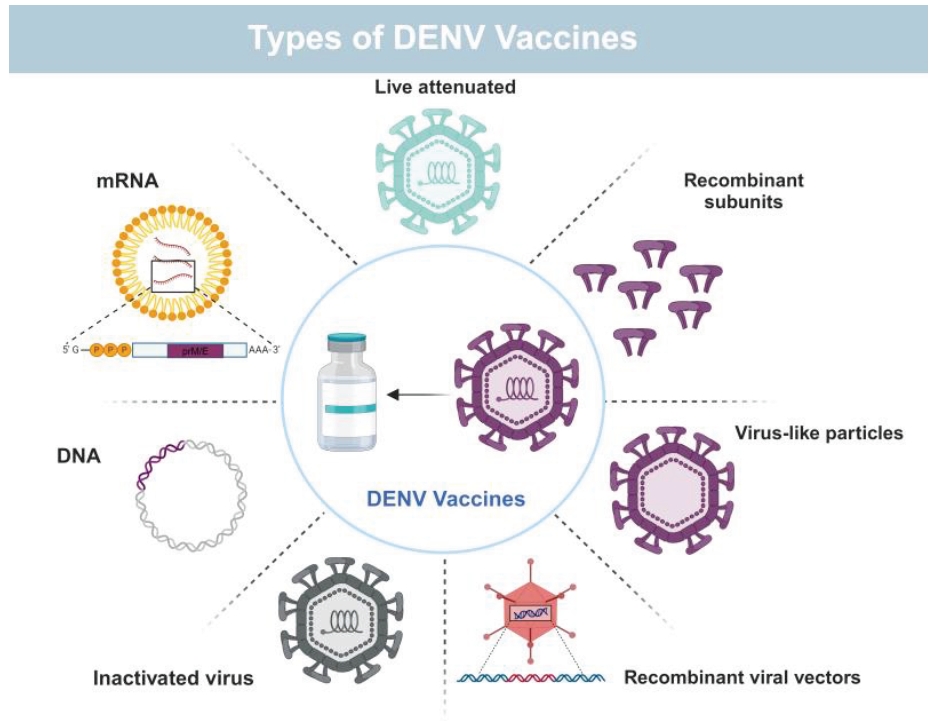

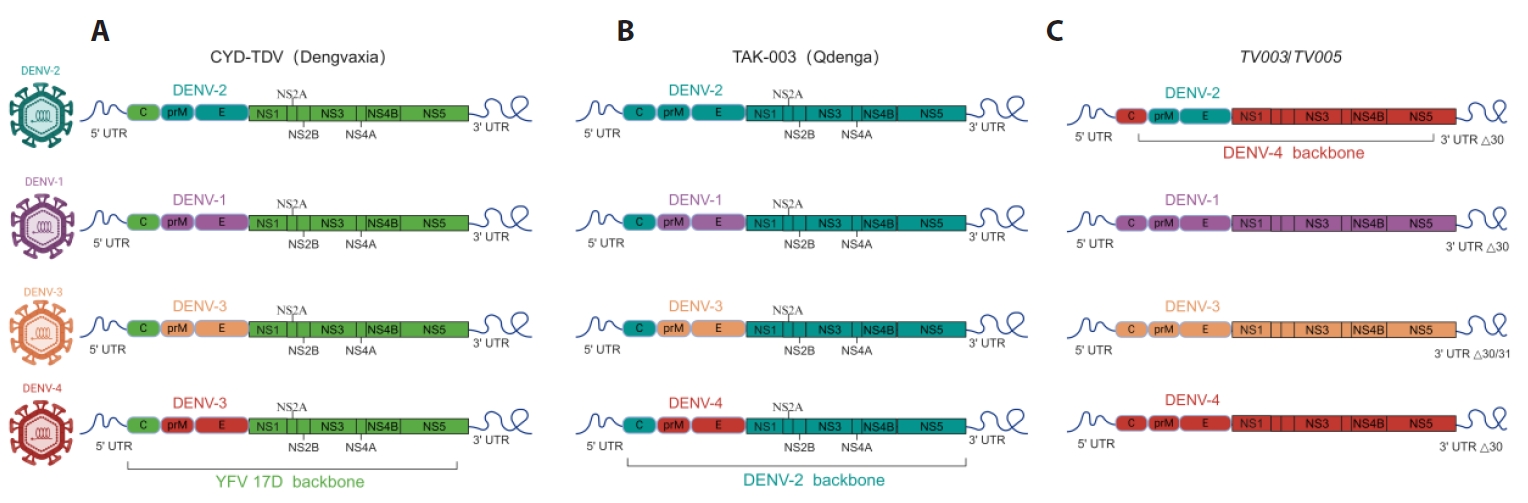

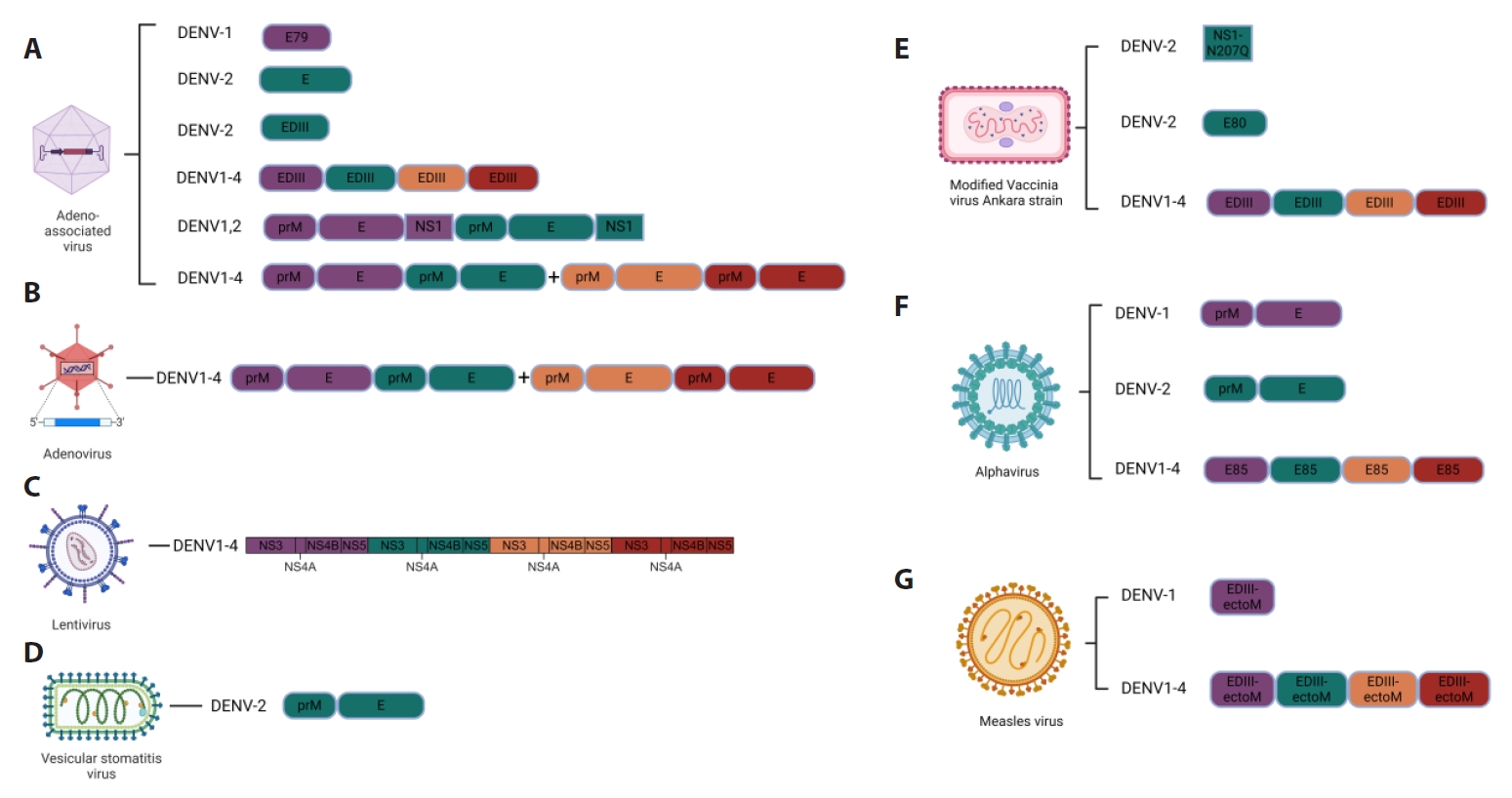

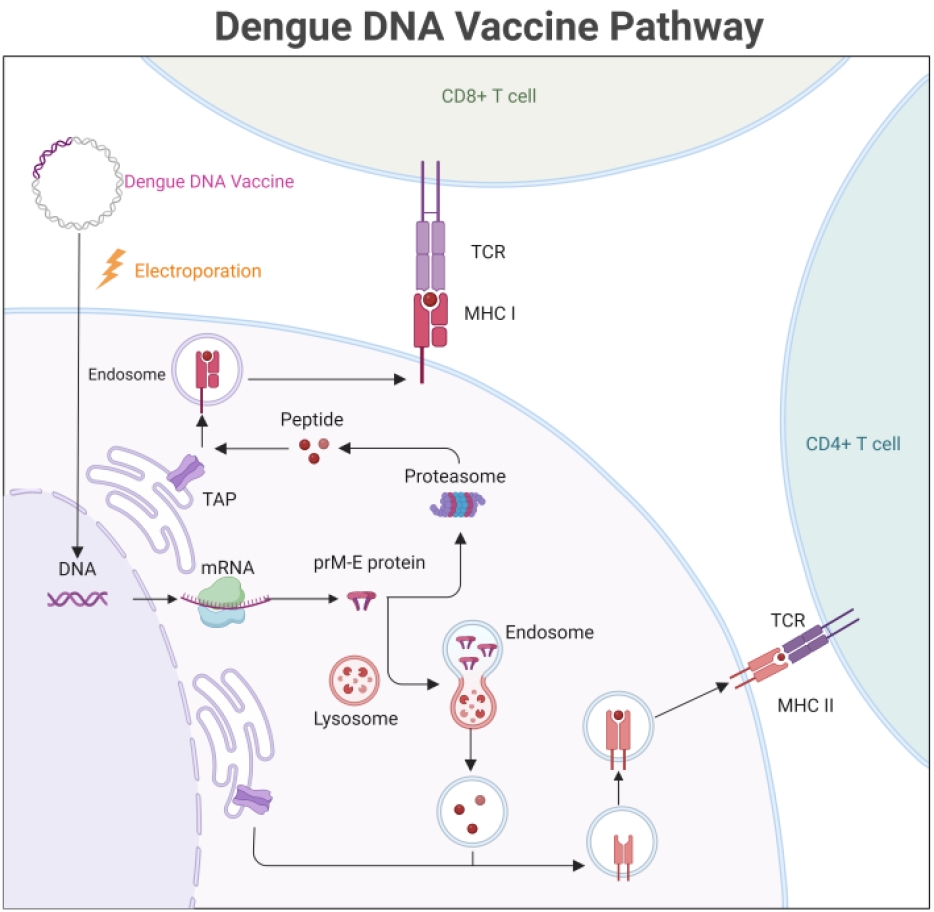

- Dengue, caused by four serotypes of dengue viruses (DENV-1 to DENV-4), is the most prevalent and widely mosquito-borne viral disease affecting humans. Dengue virus (DENV) infection has been reported in over 100 countries, and approximately half of the world's population is now at risk. The paucity of universally licensed DENV vaccines highlights the urgent need to address this public health concern. Action and attention to antibody-dependent enhancement increase the difficulty of vaccine development. With the worsening dengue fever epidemic, Dengvaxia® (CYD-TDV) and Qdenga® (TAK-003) have been approved for use in specific populations in affected areas. However, these vaccines do not provide a balanced immune response to all four DENV serotypes and the vaccination cannot cover all populations. There is still a need to develop a safe, broad-spectrum, and effective vaccine to address the increasing number of dengue cases worldwide. This review provides an overview of the existing DENV vaccines, as well as potential candidates for future studies on DENV vaccine development, and discusses the challenges and possible solutions in the field.

Introduction

Vaccines against DENV Infection

Conclusions and Future Directions

Acknowledgments

All figures were created with BioRender.com.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by Shanghai Science and technology Innovation action plan, grant number 23141902400, by Shanghai “Belt and Road” Joint Laboratory Project, grant number 22490750200.

Author Contributions

KY: writing original draft preparation. KY, LJM, JML and ZDX: writing, review and editing. JML: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

| Serotype | Inactivation method | Adjuvant | Animal models/Status | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | Formalin | Alum | Phase I: NCT01502735 | Friberg et al. (2020), Martinez et al. (2015) |

| DENV1-4 | Formalin | Alum, AS01E, AS03B | Phase I:NCT01666652,NCT01702857 | Diaz et al. (2018, 2020), Friberg et al. (2022), Schmidt et al. (2017) |

| DENV1-4 | Formalin | AS03B | Phase I/II: NCT02421367 | Lin et al. (2020b) |

| DENV1-4 | Formalin | Alum | Phase I: NCT02239614 | Lin et al. (2020a) |

| Serotype | Antigen | Expression system | Adjuvant | Animal models/Status | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV1-4 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | ISCOMATRIX™ adjuvant | Indian rhesus macaques | Govindarajan et al. (2015) |

| DENV-1 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | Alhydrogel™ | Phase I: NCT00936429 | Manoff et al. (2015) |

| DENV1-4 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | ISCOMATRIX™, Alhydrogel™ | Phase I: NCT01477580 | Manoff et al. (2019) |

| DENV1-4 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | Alhydrogel™ | Phase I: NCT02450838 | Durbin et al. (2020) |

| DENV-1 | DIII-P64k | E. coli | Freund's adjuvant | Macaca fascicularis, Rhesus monkeys | Bernardo et al. (2008) |

| DENV-2 | DIII-P64k | E. coli | Freund's adjuvant | Macaca fascicularis | Hermida et al. (2006) |

| DENV1-4 | DIII-C | E. coli | Aluminum hydroxide | American green monkeys | Suzarte et al. (2014, 2015) |

| DENV2 | DIII-C+ ODNs (m2216, poly IC and 39M) | E. coli | Aluminum hydroxide | Vervet monkeys | Gil et al. (2015) |

| DENV1-4 | cEDIII | E. coli | Aluminum hydroxide | Macaca cyclopis | Chen et al. (2013) |

| Serotype | Antigen | Expression system | Animal models | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | C-prM-E | P. pastoris | Rabbits | Sugrue et al. (1997) |

| DENV-1 | prM-E | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | Tang et al. (2012) |

| DENV1,2,3,4 | E ectodomain | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | Khetarpal et al. (2017), Mani et al. (2013), Poddar et al. (2016), Tripathi et al. (2015) |

| DENV1-2 | E | P. pastoris | BALB/c and AG129 mice | Shukla et al. (2017) |

| DENV-2 | HBcAg-EDIII-2 | E. coli | BALB/c mice | Arora et al. (2012) |

| DENV-2 | HBcAg-EDIII-2 | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | Arora et al. (2013) |

| DENV1-4 | E | P. pastoris | BALB/c and AG129 mice | Rajpoot et al. (2018) |

| DENV1-4 | EDIII-HBV S | P. pastoris | BALB/c, AG129, C57BL-6, C3H, Macaques | Ramasamy et al. (2018) |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | Liu et al. (2014) |

| DENV1-4 | prM-EF108A | FreeStyle 293F cells | BALB/c mice,NIH Swiss outbred mice | Urakami et al. (2017) |

| DENV1-4 | prM-EF108A | FreeStyle 293F cells | Cynomolgus monkeys,Common marmosets,AG129 mice | Thoresen et al. (2024) |

| DENV1-4 | C-prM-E | silkworm | BALB/c mice | Utomo et al. (2022) |

| DENV-2 | prM-E | Mosquito cells | BALB/c mice,Cynomolgus macaques | Suphatrakul et al. (2015) |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E | 293T | BALB/c mice | Zhang et al. (2011) |

| DENV-2 | C-prM-E+NS2B-NS3 | Expi293TM cells | BALB/c mice | Boigard et al. (2018) |

| DENV-1 | C-prM-E+ΔNS5 NSP | Nicotiana benthamiana | BALB/c mice | Ponndorf et al. (2021) |

| Serotype | Antigen | Delivery mode | Animal models/Status | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV1-4 | prM-E | EP,i.d. | Macaca fascicularis monkeys | Williams et al. (2019) |

| DENV-1 | prM-E | Phase I: NCT00290147 | Beckett et al. (2011) | |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E+Vaxfectin® | i.m. | Indian rhesus monkeys | Porter et al. (2012) |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E+Vaxfectin® | Phase I: NCT01502358 | Danko et al. (2018) |

- Aguiar M, Stollenwerk N, Halstead SB. 2016. The impact of the newly licensed dengue vaccine in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 10(12): e0005179. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Akter R, Tasneem F, Das S, Soma MA, Georgakopoulos-Soares I, et al. 2024. Approaches of dengue control: vaccine strategies and future aspects [review]. Front Immunol. 15: 1362780.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Ali M, Pandey RK, Khatoon N, Narula A, Mishra A, et al. 2017. Exploring dengue genome to construct a multi-epitope based subunit vaccine by utilizing immunoinformatics approach to battle against dengue infection. Sci Rep. 7(1): 9232.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Alvarez DE, De Lella Ezcurra AL, Fucito S, Gamarnik AV. 2005. Role of RNA structures present at the 3'UTR of dengue virus on translation, RNA synthesis, and viral replication. Virology. 339(2): 200–212. ArticlePubMed

- Alves R, Pereira LR, Fabris DLN, Salvador FS, Santos RA, et al. 2016. Production of a recombinant dengue virus 2 NS5 protein and potential use as a vaccine antigen. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 23(6): 460–469. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Amorim JH, Alves RP, Boscardin SB, Ferreira LC. 2014. The dengue virus non-structural 1 protein: risks and benefits. Virus Res. 181: 53–60. ArticlePubMed

- Amorim JH, Diniz MO, Cariri FA, Rodrigues JF, Bizerra RS, et al. 2012. Protective immunity to DENV2 after immunization with a recombinant NS1 protein using a genetically detoxified heat-labile toxin as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 30(5): 837–845. ArticlePubMed

- Arora U, Tyagi P, Swaminathan S, Khanna N. 2012. Chimeric Hepatitis B core antigen virus-like particles displaying the envelope domain III of dengue virus type 2. J Nanobiotechnol. 10(1): 30.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Arora U, Tyagi P, Swaminathan S, Khanna N. 2013. Virus-like particles displaying envelope domain III of dengue virus type 2 induce virus-specific antibody response in mice. Vaccine. 31(6): 873–878. ArticlePubMed

- Austin SK, Dowd KA, Shrestha B, Nelson CA, Edeling MA, et al. 2012. Structural basis of differential neutralization of DENV-1 genotypes by an antibody that recognizes a cryptic epitope. PLoS Pathog. 8(10): e1002930. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Avirutnan P, Punyadee N, Noisakran S, Komoltri C, Thiemmeca S, et al. 2006. Vascular leakage in severe dengue virus infections: a potential role for the nonstructural viral protein NS1 and complement. J Infect Dis. 193(8): 1078–1088. ArticlePubMed

- Babu JP, Pattnaik P, Gupta N, Shrivastava A, Khan M, et al. 2008. Immunogenicity of a recombinant envelope domain III protein of dengue virus type-4 with various adjuvants in mice. Vaccine. 26(36): 4655–4663. ArticlePubMed

- Bal J, Luong NN, Park J, Song KD, Jang YS, et al. 2018. Comparative immunogenicity of preparations of yeast-derived dengue oral vaccine candidate. Microb Cell Fact. 17(1): 24.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Basheer A, Jamal SB, Alzahrani B, Faheem M. 2023. Development of a tetravalent subunit vaccine against dengue virus through a vaccinomics approach. Front Immunol. 14: 1273838.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Batra G, Raut R, Dahiya S, Kamran N, Swaminathan S, et al. 2010. Pichia pastoris-expressed dengue virus type 2 envelope domain III elicits virus-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol Methods. 167(1): 10–16. ArticlePubMed

- Beatty PR, Puerta-Guardo H, Killingbeck SS, Glasner DR, Hopkins K, et al. 2015. Dengue virus NS1 triggers endothelial permeability and vascular leak that is prevented by NS1 vaccination. Sci Transl Med. 7(304): 304ra141.ArticlePubMed

- Beckett CG, Tjaden J, Burgess T, Danko JR, Tamminga C, et al. 2011. Evaluation of a prototype dengue-1 DNA vaccine in a Phase 1 clinical trial. Vaccine. 29(5): 960–968. ArticlePubMed

- Bernardo L, Fleitas O, Pavón A, Hermida L, Guillén G, et al. 2009. Antibodies induced by dengue virus type 1 and 2 envelope domain III recom-binant proteins in monkeys neutralize strains with different genotypes. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 16(12): 1829–1831. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Bernardo L, Izquierdo A, Alvarez M, Rosario D, Prado I, et al. 2008. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a recombinant fusion protein containing the domain III of the dengue 1 envelope protein in non-human primates. Antiviral Res. 80(2): 194–199. ArticlePubMed

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, et al. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 496(7446): 504–507. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Biswal S, Borja-Tabora C, Martinez Vargas L, Velásquez H, Theresa Alera M, et al. 2020. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children aged 4-16 years: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 395(10234): 1423–1433. PubMed

- Biswal S, Reynales H, Saez-Llorens X, Lopez P, Borja-Tabora C, et al. 2019. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 381(21): 2009–2019. ArticlePubMed

- Block OK, Rodrigo WW, Quinn M, Jin X, Rose RC, et al. 2010. A tetravalent recombinant dengue domain III protein vaccine stimulates neutralizing and enhancing antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 28(51): 8085–8094. ArticlePubMed

- Boigard H, Cimica V, Galarza JM. 2018. Dengue-2 virus-like particle (VLP) based vaccine elicits the highest titers of neutralizing antibodies when produced at reduced temperature. Vaccine. 36(50): 7728–7736. ArticlePubMed

- Bos S, Gadea G, Despres P. 2018. Dengue: a growing threat requiring vaccine development for disease prevention. Pathog Glob Health. 112(6): 294–305. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S, Messina JP, Brownstein JS, et al. 2018. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 6(8): e1760.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Brandler S, Lucas-Hourani M, Moris A, Frenkiel MP, Combredet C, et al. 2007. Pediatric measles vaccine expressing a dengue antigen induces durable serotype-specific neutralizing antibodies to dengue virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 1(3): e96. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Brandler S, Ruffie C, Najburg V, Frenkiel MP, Bedouelle H, et al. 2010. Pediatric measles vaccine expressing a dengue tetravalent antigen elic-its neutralizing antibodies against all four dengue viruses. Vaccine. 28(41): 6730–6739. ArticlePubMed

- Brewoo JN, Kinney RM, Powell TD, Arguello JJ, Silengo SJ, et al. 2012. Immunogenicity and efficacy of chimeric dengue vaccine (DENVax) formulations in interferon-deficient AG129 mice. Vaccine. 30(8): 1513–1520. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Callaway E. 2020. The mosquito strategy that could eliminate dengue. Nature. Retrieved 27 August 2020 from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02492-1.

- Capeding MR, Tran NH, Hadinegoro SR, Ismail HI, Chotpitayasunondh T, et al. 2014. Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children in Asia: a phase 3, randomised, observer-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 384(9951): 1358–1365. ArticlePubMed

- Chen L, Ewing D, Subramanian H, Block K, Rayner J, et al. 2007a. A heterologous DNA prime-Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particle boost dengue vaccine regimen affords complete protection from virus challenge in cynomolgus macaques. J Virol. 81(21): 11634–11639. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Chen HW, Liu SJ, Li YS, Liu HH, Tsai JP, et al. 2013. A consensus envelope protein domain III can induce neutralizing antibody responses against serotype 2 of dengue virus in non-human primates. Arch Virol. 158(7): 1523–1531. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Chen S, Yu M, Jiang T, Deng Y, Qin C, et al. 2007b. Induction of tetravalent protective immunity against four dengue serotypes by the tandem domain III of the envelope protein. DNA Cell Biol. 26(6): 361–367. Article

- Chen H, Zheng X, Wang R, Gao N, Sheng Z, et al. 2016. Immunization with electroporation enhances the protective effect of a DNA vaccine candidate expressing prME antigen against dengue virus serotype 2 infection. Clin Immunol. 171: 41–49. ArticlePubMed

- Chiang CY, Liu SJ, Tsai JP, Li YS, Chen MY, et al. 2011. A novel single-dose dengue subunit vaccine induces memory immune responses. PLoS One. 6(8): e23319. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Danko JR, Kochel T, Teneza-Mora N, Luke TC, Raviprakash K, et al. 2018. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent dengue DNA vaccine administered with a cationic lipid-based adjuvant in a phase 1 clinical trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 98(3): 849–856. ArticlePubMedPMC

- De Paula SO, Lima DM, de Oliveira França RF, Gomes-Ruiz AC, da Fonseca BAL. 2008. A DNA vaccine candidate expressing dengue-3 virus prM and E proteins elicits neutralizing antibodies and protects mice against lethal challenge. Arch Virol. 153(12): 2215–2223. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Deng SQ, Yang X, Wei Y, Chen JT, Wang XJ, et al. 2020. A review on dengue vaccine development. Vaccines. 8(1): 63.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Dengue vaccine recommendations. Retrieved June 28, 2024 from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/dengue/hcp/recommendations.html

- Dengue vaccine: WHO position paper, September 2018 - Recommendations. 2019. Vaccine. 37(35): 4848–4849. ArticlePubMed

- Dias RS, Teixeira MD, Xisto MF, Prates JWO, Silva JDD, et al. 2021. DENV-3 precursor membrane (prM) glycoprotein enhances E protein immunogenicity and confers protection against DENV-2 infections in a murine model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 17(5): 1271–1277. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Diaz C, Koren M, Lin L, Martinez LJ, Eckels KH, et al. 2020. Safety and immunogenicity of different formulations of a tetravalent dengue purified inactivated vaccine in healthy adults from Puerto Rico: Final results after 3 years of follow-up from a randomized, placebo-controlled phase I study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 102(5): 951–954. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Diaz C, Lin L, Martinez LJ, Eckels KH, Campos M, et al. 2018. Phase I randomized study of a tetravalent dengue purified inactivated vaccine in healthy adults from Puerto Rico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 98(5): 1435–1443. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Donmez BB. 2023. Half of world population at risk of dengue virus: WHO mosquito-borne virus causes 40,000 to 70,000 deaths per year, according to WHO estimates. AA. Retrieved 21.07.2023 - Update: 22.07.2023 from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/health/half-of-world-population-at-risk-of-dengue-virus-who/2951296

- Durbin AP, Kirkpatrick BD, Pierce KK, Elwood D, Larsson CJ, et al. 2013. A single dose of any of four different live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccines is safe and immunogenic in flavivirus-naive adults: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 207(6): 957–965. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Durbin AP, Pierce KK, Kirkpatrick BD, Grier P, Sabundayo BP, et al. 2020. Immunogenicity and safety of a tetravalent recombinant subunit dengue vaccine in adults previously vaccinated with a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine: Results of a phase-I randomized clinical trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 103(2): 855–863. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Etemad B, Batra G, Raut R, Dahiya S, Khanam S, et al. 2008. An envelope domain III-based chimeric antigen produced in Pichia pastoris elicits neutralizing antibodies against all four dengue virus serotypes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 79(3): 353–363. ArticlePubMed

- Fadaka AO, Sibuyi NRS, Martin DR, Goboza M, Klein A, et al. 2021. Immunoinformatics design of a novel epitope-based vaccine candidate against dengue virus. Sci Rep. 11(1): 19707.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Falconar AK. 1999. Identification of an epitope on the dengue virus membrane (M) protein defined by cross-protective monoclonal antibodies: Design of an improved epitope sequence based on common determinants present in both envelope (E and M) proteins. Arch Virol. 144(12): 2313–2330. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Fan YC, Chen JM, Chen YY, Hsu WL, Chang GJ, et al. 2024. Low-temperature culture enhances production of flavivirus virus-like particles in mammalian cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 108(1): 242.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Fang E, Liu X, Li M, Zhang Z, Song L, et al. 2022. Advances in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7(1): 94.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Feng K, Zheng X, Wang R, Gao N, Fan D, et al. 2020. Long-term protection elicited by a DNA vaccine candidate expressing the prM-E antigen of dengue virus serotype 3 in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 10: 87.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Forrat R, Dayan GH, DiazGranados CA, Bonaparte M, Laot T, et al. 2021. Analysis of hospitalized and severe dengue cases over the 6 years of follow-up of the tetravalent dengue vaccine (CYD-TDV) efficacy trials in Asia and Latin America. Clin Infect Dis. 73(6): 1003–1012. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Friberg H, Gargulak M, Kong A, Lin L, Martinez LJ, et al. 2022. Characterization of B-cell and T-cell responses to a tetravalent dengue purified inactivated vaccine in healthy adults. NPJ Vaccines. 7(1): 132.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Friberg H, Martinez LJ, Lin L, Blaylock JM, De La Barrera RA, et al. 2020. Cell-mediated immunity generated in response to a purified inactivated vaccine for dengue virus type 1. mSphere. 5(1): e00671–19. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Fuchs J, Chu H, O'Day P, Pyles R, Bourne N, et al. 2014. Investigating the efficacy of monovalent and tetravalent dengue vaccine formulations against DENV-4 challenge in AG129 mice. Vaccine. 32(48): 6537–6543. ArticlePubMedPMC

- García-Machorro J, López-González M, Barrios-Rojas O, Fernández-Pomares C, Sandoval-Montes C, et al. 2013. DENV-2 subunit proteins fused to CR2 receptor-binding domain (P28)-induces specific and neutralizing antibodies to the dengue virus in mice. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 9(11): 2326–2335. ArticlePubMedPMC

- George SL, Wong MA, Dube TJ, Boroughs KL, Stovall JL, et al. 2015. Safety and immunogenicity of a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine candidate in flavivirus-naive adults: A randomized, double-blinded phase 1 clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 212(7): 1032–1041. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Gil L, Cobas K, Lazo L, Marcos E, Hernández L, et al. 2016. A tetravalent formulation based on recombinant nucleocapsid-like particles from dengue viruses induces a functional immune response in mice and monkeys. J Immunol. 197(9): 3597–3606. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Gil L, Marcos E, Izquierdo A, Lazo L, Valdés I, et al. 2015. The protein DIIIC-2, aggregated with a specific oligodeoxynucleotide and adjuvanted in alum, protects mice and monkeys against DENV-2. Immunol Cell Biol. 93(1): 57–66. ArticlePubMedLink

- Glasner DR, Puerta-Guardo H, Beatty PR, Harris E. 2018. The good, the bad, and the shocking: The multiple roles of dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 in protection and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Virol. 5(1): 227–253. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Govindarajan D, Meschino S, Guan L, Clements DE, ter Meulen JH, et al. 2015. Preclinical development of a dengue tetravalent recombinant subunit vaccine: Immunogenicity and protective efficacy in nonhuman primates. Vaccine. 33(33): 4105–4116. ArticlePubMed

- Guirakhoo F, Arroyo J, Pugachev KV, Miller C, Zhang ZX, et al. 2001. Construction, safety, and immunogenicity in nonhuman primates of a chimeric yellow fever-dengue virus tetravalent vaccine. J Virol. 75(16): 7290–7304. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Guirakhoo F, Kitchener S, Morrison D, Forrat R, McCarthy K, et al. 2006. Live attenuated chimeric yellow fever dengue type 2 (ChimeriVax-DEN2) vaccine: Phase I clinical trial for safety and immunogenicity: Effect of yellow fever pre-immunity in induction of cross neutralizing antibody responses to all 4 dengue serotypes. Hum Vaccin. 2(2): 60–67. PubMed

- Guirakhoo F, Weltzin R, Chambers TJ, Zhang ZX, Soike K, et al. 2000. Recombinant chimeric yellow fever-dengue type 2 virus is immunogenic and protective in nonhuman primates. J Virol. 74(12): 5477–5485. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Guy B, Briand O, Lang J, Saville M, Jackson N. 2015. Development of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine: One more step forward. Vaccine. 33(50): 7100–7111. ArticlePubMed

- Guy B, Noriega F, Ochiai RL, L’azou M, Delore V, et al. 2017. A recombinant live attenuated tetravalent vaccine for the prevention of dengue. Expert Rev Vaccines. 16(7): 671–684. Article

- Guy B, Saville M, Lang J. 2010. Development of Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 6(9): 10.4161.hv.6.9.12739. Article

- Guzman MG, Gubler DJ, Izquierdo A, Martinez E, Halstead SB. 2016. Dengue infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2(1): 1–25. ArticlePDF

- Guzman MG, Harris E. 2015. Dengue. Lancet. 385(9966): 453–465. ArticlePubMed

- Hadinegoro SR, Arredondo-García JL, Capeding MR, Deseda C, Chotpitayasunondh T, et al. 2015. Efficacy and long-term safety of a dengue vaccine in regions of endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 373(13): 1195–1206. ArticlePubMed

- Halstead SB. 2017. Dengvaxia sensitizes seronegatives to vaccine enhanced disease regardless of age. Vaccine. 35(47): 6355–6358. ArticlePubMed

- Halstead SB. 2024. Delivering safe dengue vaccines. Lancet Glob Health. 12(8): e1229–e1230. ArticlePubMed

- Halstead SB, Katzelnick LC, Russell PK, Markoff L, Aguiar M, et al. 2020. Ethics of a partially effective dengue vaccine: Lessons from the Philippines. Vaccine. 38(35): 5572–5576. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Halstead SB, Nimmannitya S, Cohen SN. 1970. Observations related to pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. IV. Relation of disease severity to antibody response and virus recovered. Yale J Biol Med. 42(5): 311–328. PubMedPMC

- Halstead SB, O'Rourke EJ. 1977. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody. J Exp Med. 146(1): 201–217. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Harahap-Carrillo IS, Ceballos-Olvera I, Valle JR-d. 2015. Immunogenic subviral particles displaying domain III of dengue 2 envelope protein vectored by measles virus. Vaccines. 3(3): 503–518. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Hasan SS, Sevvana M, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2018. Structural biology of Zika virus and other flaviviruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 25(1): 13–20. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Hashem AM, Sohrab SS, El-Kafrawy SA, El-Ela SA, Abd-Alla AMM, et al. 2018. First complete genome sequence of circulating dengue virus serotype 3 in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. New Microbes New Infect. 21: 9–11. ArticlePubMedPMC

- He L, Sun W, Yang L, Liu W, Li J. 2022. A multiple-target mRNA-LNP vaccine induces protective immunity against experimental multi-serotype DENV in mice. Virol. Sin. 37(5): 746–757. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Henriques HR, Rampazo EV, Gonçalves AJS, Vicentin ECM, Amorim JH, et al. 2013. Targeting the non-structural protein 1 from dengue virus to a dendritic cell population confers protective immunity to lethal virus challenge. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 7(7): e2330. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Hermida L, Bernardo L, Martín J, Alvarez M, Prado I, et al. 2006. A recombinant fusion protein containing the domain III of the dengue-2 envelope protein is immunogenic and protective in nonhuman primates. Vaccine. 24(16): 3165–3171. ArticlePubMed

- Hermida L, Rodríguez R, Lazo L, Bernardo L, Silva R, et al. 2004a. A fragment of the envelope protein from dengue-1 virus, fused in two different sites of the meningococcal P64k protein carrier, induces a functional immune response in mice. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 39(1): 107–114. Article

- Hermida L, Rodríguez R, Lazo L, Silva R, Zulueta A, et al. 2004b. A dengue-2 envelope fragment inserted within the structure of the P64k meningococcal protein carrier enables a functional immune response against the virus in mice. J Virol Methods. 115(1): 41–49. Article

- Holman DH, Wang D, Raviprakash K, Raja NU, Luo M, et al. 2007. Two complex, adenovirus-based vaccines that together induce immune responses to all four dengue virus serotypes. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 14(2): 182–189. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Hou J, Ye W, Chen J. 2022. Current development and challenges of tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccines. Front Immunol. 13: 811243.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Hussain M, Idrees M, Afzal S. 2015. Development of global consensus of dengue virus envelope glycoprotein for epitopes based vaccine design. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 11(1): 84–97. ArticlePubMed

- Huy NX, Kim MY. 2017. Overexpression and oral immunogenicity of a dengue antigen transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 131(3): 567–577. ArticlePDF

- Increasing risk of mosquito-borne diseases in EU/EEA following spread of Aedes species. 2023 Jun 22. Retrieved 22 Jun 2023 from https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/increasing-risk-mosquito-borne-diseases-eueea-following-spread-aedes-species

- Izquierdo A, García A, Lazo L, Gil L, Marcos E, et al. 2014. A tetravalent dengue vaccine containing a mix of domain III-P64k and domain III-capsid proteins induces a protective response in mice. Arch Virol. 159(10): 2597–2604. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Jaiswal S, Khanna N, Swaminathan S. 2003. Replication-defective adenoviral vaccine vector for the induction of immune responses to dengue virus type 2. J Virol. 77(23): 12907–12913. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Kallás EG, Cintra MAT, Moreira JA, Patiño EG, Braga PE, et al. 2024. Live, attenuated, tetravalent butantan-dengue vaccine in children and adults. N Engl J Med. 390(5): 397–408. PubMed

- Kallas EG, Precioso AR, Palacios R, Thomé B, Braga PE, et al. 2020. Safety and immunogenicity of the tetravalent, live-attenuated dengue vaccine Butantan-DV in adults in Brazil: a two-step, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 20(7): 839–850. ArticlePubMed

- Kanai R, Kar K, Anthony K, Gould LH, Ledizet M, et al. 2006. Crystal structure of west nile virus envelope glycoprotein reveals viral surface epitopes. J Virol. 80(22): 11000–11008. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Kang C, Keller TH, Luo D. 2017. Zika virus protease: An antiviral drug target. Trends Microbiol. 25(10): 797–808. ArticlePubMed

- Kao YS, Yu CY, Huang HJ, Tien SM, Wang WY, et al. 2019. Combination of modified NS1 and NS3 as a novel vaccine strategy against Dengue virus infection. J Immunol. 203(7): 1909–1917. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Kariyawasam R, Lachman M, Mansuri S, Chakrabarti S, Boggild AK. 2023. A dengue vaccine whirlwind update. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 10: 20499361231167274.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Khalil SM, Tonkin DR, Mattocks MD, Snead AT, Johnston RE, et al. 2014. A tetravalent alphavirus-vector based dengue vaccine provides effective immunity in an early life mouse model. Vaccine. 32(32): 4068–4074. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Khan KH. 2013. DNA vaccines: Roles against diseases [Review]. GERMS. 3(1): 26–35. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Khanam S, Khanna N, Swaminathan S. 2006. Induction of neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses by dengue virus type 2 envelope domain III encoded by plasmid and adenoviral vectors. Vaccine. 24(42-43): 6513–6525. ArticlePubMed

- Khanam S, Pilankatta R, Khanna N, Swaminathan S. 2009. An adenovirus type 5 (AdV5) vector encoding an envelope domain III-based tetravalent antigen elicits immune responses against all four dengue viruses in the presence of prior AdV5 immunity. Vaccine. 27(43): 6011–6021. ArticlePubMed

- Khetarpal N, Shukla R, Rajpoot RK, Poddar A, Pal M, et al. 2017. Recombinant Dengue virus 4 envelope glycoprotein virus-like particles derived from Pichia pastoris are capable of eliciting homotypic domain III-directed neutralizing antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 96(1): 126–134. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kim BY, Kim MY. 2019. Evaluation of the oral immunogenicity of M cell-targeted tetravalent EDIII antigen for development of plant-based edible vaccine against dengue infection. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult (PCTOC). 137(1): 1–10. ArticlePDF

- Kim MY, Van Dolleweerd C, Copland A, Paul MJ, Hofmann S, et al. 2017. Molecular engineering and plant expression of an immunoglobulin heavy chain scaffold for delivery of a dengue vaccine candidate. Plant Biotechnol J. 15(12): 1590–1601. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Kirkpatrick BD, Durbin AP, Pierce KK, Carmolli MP, Tibery CM, et al. 2015. Robust and balanced immune responses to all 4 dengue virus serotypes following administration of a single dose of a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine to healthy, flavivirus-naive adults. J Infect Dis. 212(5): 702–710. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kirkpatrick BD, Whitehead SS, Pierce KK, Tibery CM, Grier PL, et al. 2016. The live attenuated dengue vaccine TV003 elicits complete protection against dengue in a human challenge model. Sci Transl Med. 8(330): 330ra336.Article

- Kuno G, Chang GJ. 2007. Full-length sequencing and genomic characterization of Bagaza, Kedougou, and Zika viruses. Arch Virol. 152(4): 687–696. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Lauretti F, Chattopadhyay A, de Oliveira França RF, Castro-Jorge L, Rose J, et al. 2016. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based dengue-2 vaccine candidate induces humoral response and protects mice against lethal infection. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 12(9): 2327–2333.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lazo L, Izquierdo A, Suzarte E, Gil L, Valdés I, et al. 2014. Evaluation in mice of the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tetravalent subunit vaccine candidate against dengue virus. Microbiol Immunol. 58(4): 219–226. ArticlePubMed

- Lazo L, Zulueta A, Hermida L, Blanco A, Sánchez J, et al. 2009. Dengue-4 envelope domain III fused twice within the meningococcal P64k protein carrier induces partial protection in mice. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 52(4): 265–271. ArticlePubMed

- Leng CH, Liu SJ, Tsai JP, Li YS, Chen MY, et al. 2009. A novel dengue vaccine candidate that induces cross-neutralizing antibodies and memory immunity. Microbes Infect. 11(2): 288–295. ArticlePubMed

- Li X, Cao H, Wang Q, Di B, Wang M, et al. 2012. Novel AAV-based genetic vaccines encoding truncated dengue virus envelope proteins elicit humoral immune responses in mice. Microbes Infect. 14(11): 1000–1007. ArticlePubMed

- Lima DM, de Paula SO, França RF, Palma PV, Morais FR, et al. 2011. A DNA vaccine candidate encoding the structural prM/E proteins elicits a strong immune response and protects mice against dengue-4 virus infection. Vaccine. 29(4): 831–838. ArticlePubMed

- Lin L, Koren MA, Paolino KM, Eckels KH, De La Barrera R, et al. 2020a. Immunogenicity of a live-attenuated dengue vaccine using a heterologous prime-boost strategy in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 223(10): 1707–1716. ArticlePDF

- Lin L, Lyke KE, Koren M, Jarman RG, Eckels KH, et al. 2020b. Safety and immunogenicity of an AS03(B)-adjuvanted inactivated tetravalent dengue virus vaccine administered on varying schedules to healthy U.S. adults: A phase 1/2 randomized study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 103(1): 132–141. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lindow JC, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierce KK, Carmolli MP, et al. 2013. Vaccination of volunteers with low-dose, live-attenuated, dengue viruses leads to serotype-specific immunologic and virologic profiles. Vaccine. 31(33): 3347–3352. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Liu Y, Zhou J, Yu Z, Fang D, Fu C, et al. 2014. Tetravalent recombinant dengue virus-like particles as potential vaccine candidates: Immunological properties. BMC Microbiol. 14: 233.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Lok SM, Kostyuchenko V, Nybakken GE, Holdaway HA, Battisti AJ, et al. 2008. Binding of a neutralizing antibody to dengue virus alters the arrangement of surface glycoproteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 15(3): 312–317. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Londono-Renteria B, Troupin A, Colpitts TM. 2016. Arbovirosis and potential transmission blocking vaccines. Parasit Vectors. 9(1): 516.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Lu H, Xu XF, Gao N, Fan DY, Wang J, et al. 2013. Preliminary evaluation of DNA vaccine candidates encoding dengue-2 prM/E and NS1: their immunity and protective efficacy in mice. Mol Immunol. 54(2): 109–114. ArticlePubMed

- Lühn K, Simmons CP, Moran E, Dung NTP, Chau TNB, et al. 2007. Increased frequencies of CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in acute dengue infection. J Exp Med. 204(5): 979–985. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Lundstrom K. 2020. Application of viral vectors for vaccine development with a special emphasis on COVID-19. Viruses. 12(11): Article

- Luplerdlop N, Missé D, Bray D, Deleuze V, Gonzalez JP, et al. 2006. Dengue-virus-infected dendritic cells trigger vascular leakage through metalloproteinase overproduction. EMBO Rep. 7(11): 1176–1181. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Mallapaty S. 2022. Dengue vaccine poised for roll-out but safety concerns linger. Nature. 611(7936): 434–435. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Mani S, Tripathi L, Raut R, Tyagi P, Arora U, et al. 2013. Pichia pastoris-expressed dengue 2 envelope forms virus-like particles without pre-membrane protein and induces high titer neutralizing antibodies. PLoS One. 8(5): e64595. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Manoff SB, George SL, Bett AJ, Yelmene ML, Dhanasekaran G, et al. 2015. Preclinical and clinical development of a dengue recombinant subunit vaccine. Vaccine. 33(50): 7126–7134. ArticlePubMed

- Manoff SB, Sausser M, Falk Russell A, Martin J, Radley D, et al. 2019. Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational tetravalent recombinant subunit vaccine for dengue: Results of a phase I randomized clinical trial in flavivirus-naïve adults. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 15(9): 2195–2204. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Manoj S, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2004. Approaches to enhance the efficacy of DNA vaccines. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 41(1): 1–39. ArticlePubMed

- Martinez LJ, Lin L, Blaylock JM, Lyons AG, Bauer KM, et al. 2015. Safety and immunogenicity of a dengue virus serotype-1 purified-inactivated vaccine: Results of a phase 1 clinical trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 93(3): 454–460. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Maves RC, Castillo Oré RM, Porter KR, Kochel TJ. 2010. Immunogenicity of a psoralen-inactivated dengue virus type 1 vaccine candidate in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 17(2): 304–306. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Maves RC, Oré RMC, Porter KR, Kochel TJ. 2011. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a psoralen-inactivated dengue-1 virus vaccine candidate in Aotus nancymaae monkeys. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 29(15): 2691–2696. Article

- Men R, Bray M, Clark D, Chanock RM, Lai CJ. 1996. Dengue type 4 virus mutants containing deletions in the 3' noncoding region of the RNA genome: analysis of growth restriction in cell culture and altered viremia pattern and immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 70(6): 3930–3937. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Men R, Wyatt L, Tokimatsu I, Arakaki S, Shameem G, Elkins R, Chanock R, Moss B, Lai CJ. 2000. Immunization of rhesus monkeys with a recombinant of modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing a truncated envelope glycoprotein of dengue type 2 virus induced resistance to dengue type 2 virus challenge. Vaccine. 18(27): 3113–3122. ArticlePubMed

- Minor PD. 2015. Live attenuated vaccines: Historical successes and current challenges. Virology. 479-480: 379–392. ArticlePubMed

- Mintaev RR, Glazkova DV, Orlova OV, Ignatyev GM, Oksanich AS, Shipulin GA, Bogoslovskaya EV. 2023. Development of MVA-d34 tetravalent dengue vaccine: Design and immunogenicity. Vaccines (Basel). 11(4): 831.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Mondiale de la Santé O, Organization WH. 2024. WHO position paper on dengue vaccines–May 2024 = Note de synthèse: position de l’OMS sur les vaccins contre la dengue–mai 2024. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 203–224

- Mukhtar M, Wajeeha AW, Zaidi N, Bibi N. 2022. Engineering modified mRNA-based vaccine against dengue virus using computational and reverse vaccinology approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 23(22): 13911.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Nasar S, Iftikhar S, Saleem R, Nadeem MS, Ali M. 2024. The N and C-terminal deleted variant of the dengue virus NS1 protein is a potential candidate for dengue vaccine development. Sci Rep. 14(1): 18883.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Nemirov K, Authié P, Souque P, Moncoq F, Noirat A, et al. 2023. Preclinical proof of concept of a tetravalent lentiviral T-cell vaccine against dengue viruses. Front Immunol. 14: 1208041.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Nguyen NL, Kim JM, Park JA, Park SM, Jang YS, et al. 2013. Expression and purification of an immunogenic dengue virus epitope using a synthetic consensus sequence of envelope domain III and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr Purif. 88(2): 235–242. ArticlePubMed

- Nooraei S, Bahrulolum H, Hoseini ZS, Katalani C, Hajizade A, et al. 2021. Virus-like particles: preparation, immunogenicity and their roles as nanovaccines and drug nanocarriers. J Nanobiotechnol. 19(1): 59.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Normile D. 2013. Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts. Science. 342(6157): 415.ArticlePubMed

- Osorio JE, Brewoo JN, Silengo SJ, Arguello J, Moldovan IR, et al. 2011a. Efficacy of a tetravalent chimeric dengue vaccine (DENVax) in Cynomolgus macaques. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 84(6): 978–987. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Osorio JE, Huang CY, Kinney RM, Stinchcomb DT. 2011b. Development of DENVax: a chimeric dengue-2 PDK-53-based tetravalent vaccine for protection against dengue fever. Vaccine. 29(42): 7251–7260. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Osorio JE, Velez ID, Thomson C, Lopez L, Jimenez A, et al. 2014. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine (DENVax) in flavivirus-naive healthy adults in Colombia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 study. Lancet Infect Dis. 14(9): 830–838. PubMedPMC

- Patel SS, Winkle P, Faccin A, Nordio F, LeFevre I, et al. 2023. An open-label, Phase 3 trial of TAK-003, a live attenuated dengue tetravalent vaccine, in healthy US adults: immunogenicity and safety when administered during the second half of a 24-month shelf-life. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 19(2): 2254964.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Paz-Bailey G, Adams L, Wong JM, Poehling KA, Chen WH, et al. 2021. Dengue vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 70(6): 1–16. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Pinheiro JR, Camilo Dos Reis E, Souza R, Rocha ALS, Suesdek L, et al. 2021. Comparison of neutralizing dengue virus B cell epitopes and protective T cell epitopes with those in three main dengue virus vaccines. Front Immunol. 12: 715136.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Pintado Silva J, Fernandez-Sesma A. 2023. Challenges on the development of a dengue vaccine: a comprehensive review of the state of the art. J Gen Virol. 104(3): 001831.PubMedPMC

- Pinto PBA, Barros TAC, Lima LM, Pacheco AR, Assis ML, et al. 2022. Combination of E- and NS1-derived DNA vaccines: The immune response and protection elicited in mice against DENV2. Viruses. 14(7): 1452.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Poddar A, Ramasamy V, Shukla R, Rajpoot RK, Arora U, et al. 2016. Virus-like particles derived from Pichia pastoris-expressed dengue virus type 1 glycoprotein elicit homotypic virus-neutralizing envelope domain III-directed antibodies. BMC Biotechnol. 16(1): 50.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Ponndorf D, Meshcheriakova Y, Thuenemann EC, Dobon Alonso A, Overman R, et al. 2021. Plant-made dengue virus-like particles produced by co-expression of structural and non-structural proteins induce a humoral immune response in mice. Plant Biotechnol J. 19(4): 745–756. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Porter KR, Ewing D, Chen L, Wu SJ, Hayes CG, et al. 2012. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a vaxfectin-adjuvanted tetravalent dengue DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 30(2): 336–341. ArticlePubMed

- Precioso AR, Palacios R, Thomé B, Mondini G, Braga P, et al. 2015. Clinical evaluation strategies for a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine. Vaccine. 33(50): 7121–7125. ArticlePubMed

- Prompetchara E, Ketloy C, Thomas SJ, Ruxrungtham K. 2020. Dengue vaccine: Global development update. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 38(3): 178–185. PubMed

- Puerta-Guardo H, Raya-Sandino A, González-Mariscal L, Rosales VH, Ayala-Dávila J, et al. 2013. The cytokine response of U937-derived macrophages infected through antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus disrupts cell apical-junction complexes and increases vascular permeability. J Virol. 87(13): 7486–7501. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Putnak R, Barvir DA, Burrous JM, Dubois DR, D'Andrea VM, et al. 1996a. Development of a purified, inactivated, dengue-2 virus vaccine proto-type in Vero cells: Immunogenicity and protection in mice and rhesus monkeys. J Infect Dis. 174(6): 1176–1184. Article

- Putnak R, Cassidy K, Conforti N, Lee R, Sollazzo D, et al. 1996b. Immunogenic and protective response in mice immunized with a purified, inactivated, dengue-2 virus vaccine prototype made in fetal rhesus lung cells. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 55(5): 504–510. Article

- Rajpoot RK, Shukla R, Arora U, Swaminathan S, Khanna N. 2018. Dengue envelope-based 'four-in-one' virus-like particles produced using Pichia pastoris induce enhancement-lacking, domain III-directed tetravalent neutralising antibodies in mice. Sci Rep. 8(1): 8643.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Ramasamy V, Arora U, Shukla R, Poddar A, Shanmugam RK, et al. 2018. A tetravalent virus-like particle vaccine designed to display domain III of dengue envelope proteins induces multi-serotype neutralizing antibodies in mice and macaques which confer protection against antibody dependent enhancement in AG129 mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 12(1): e0006191. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Ramírez R, Falcón R, Izquierdo A, García A, Alvarez M, et al. 2014. Recombinant dengue 2 virus NS3 protein conserves structural antigenic and immunological properties relevant for dengue vaccine design. Virus Genes. 49(2): 185–195. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Raviprakash K, Luke T, Doukas J, Danko J, Porter K, et al. 2012. A dengue DNA vaccine formulated with Vaxfectin® is well tolerated, and elicits strong neutralizing antibody responses to all four dengue serotypes in New Zealand white rabbits. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 8(12): 1764–1768. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Raviprakash K, Sun P, Raviv Y, Luke T, Martin N, et al. 2013. Dengue virus photo-inactivated in presence of 1,5-iodonaphthylazide (INA) or AMT, a psoralen compound (4′-aminomethyl-trioxsalen) is highly immunogenic in mice. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 9(11): 2336–2341. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Raviprakash K, Wang D, Ewing D, Holman DH, Block K, et al. 2008. A tetravalent dengue vaccine based on a complex adenovirus vector provides significant protection in rhesus monkeys against all four serotypes of dengue virus. J Virol. 82(14): 6927–6934. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Rico-Hesse R. 2003. Microevolution and virulence of dengue viruses. Adv Virus Res. 59: 315.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Rocklöv J, Quam MB, Sudre B, German M, Kraemer MU, et al. 2016. Assessing seasonal risks for the introduction and mosquito-borne spread of Zika virus in Europe. EBioMedicine. 9: 250–256. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Putnak RJ, Coller BA, Voss G, Vaughn DW, Clements D, et al. 2005. An evaluation of dengue type-2 inactivated, recombinant subunit, and live-attenuated vaccine candidates in the rhesus macaque model. Vaccine. 23(35): 4442–4452. ArticlePubMed

- Roth C, Cantaert T, Colas C, Prot M, Casadémont I, et al. 2019. A modified mRNA vaccine targeting immunodominant NS epitopes protects against dengue virus infection in HLA class I transgenic mice. Front Immunol. 10: 1424.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Rothman AL. 2004. Dengue: defining protective versus pathologic immunity. J Clin Invest. 113(7): 946–951. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Rothman AL. 2011. Immunity to dengue virus: a tale of original antigenic sin and tropical cytokine storms. Nat Rev Immunol. 11(8): 532–543. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Sabchareon A, Wallace D, Sirivichayakul C, Limkittikul K, Chanthavanich P, et al. 2012. Protective efficacy of the recombinant, live-attenuated, CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine in Thai schoolchildren: a randomised, controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 380(9853): 1559–1567. ArticlePubMed

- Sabir MJ, Al-Saud NBS, Hassan SM. 2021. Dengue and human health: A global scenario of its occurrence, diagnosis and therapeutics. Saudi J Biol Sci. 28(9): 5074–5080. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Sangkawibha N, Rojanasuphot S, Ahandrik S, Viriyapongse S, Jatanasen S, et al. 1984. Risk factors in dengue shock syndrome: a prospective epidemiologic study in Rayong, Thailand. I. The 1980 outbreak. Am J Epidemiol. 120(5): 653–669. PubMed

- Sarker A, Dhama N, Gupta RD. 2023. Dengue virus neutralizing antibody: a review of targets, cross-reactivity, and antibody-dependent enhancement. Front Immunol. 14: 1200195.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Schmidt AC, Lin L, Martinez LJ, Ruck RC, Eckels KH, et al. 2017. Phase 1 randomized study of a tetravalent dengue purified inactivated vaccine in healthy adults in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 96(6): 1325–1337. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Sheng Z, Chen H, Feng K, Gao N, Wang R, et al. 2019. Electroporation-mediated immunization of a candidate DNA vaccine expressing dengue virus serotype 4 prM-E antigen confers long-term protection in mice. Virol Sin. 34(1): 88–96. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Shepard DS, Undurraga EA, Halasa YA, Stanaway JD. 2016. The global economic burden of dengue: a systematic analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16(8): 935–941.ArticlePubMed

- Shukla R, Rajpoot RK, Arora U, Poddar A, Swaminathan S, et al. 2017. Pichia pastoris-expressed bivalent virus-like particulate vaccine induces domain III-focused bivalent neutralizing antibodies without antibody-dependent enhancement in vivo. Front Microbiol. 8: 2644.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Shukla R, Ramasamy V, Shanmugam RK, Ahuja R, Khanna N. 2020. Antibody-dependent enhancement: A challenge for developing a safe dengue vaccine. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 10: 572681.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Simmons CP, Farrar JJ, Nguyen V, Wills B. 2012. Dengue. N Engl J Med. 366(15): 1423–1432. ArticlePubMed

- Simmons M, Burgess T, Lynch J, Putnak R. 2010. Protection against dengue virus by non-replicating and live attenuated vaccines used together in a prime boost vaccination strategy. Virology. 396(2): 280–288. ArticlePubMed

- Sirivichayakul C, Barranco-Santana EA, Esquilin-Rivera I, Oh HML, Raanan M, et al. 2015. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent dengue vaccine candidate in healthy children and adults in dengue-endemic regions: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. J Infect Dis. 213(10): 1562–1572. ArticlePubMed

- Soo KM, Khalid B, Ching SM, Chee HY. 2016. Meta-analysis of dengue severity during infection by different dengue virus serotypes in primary and secondary infections. PLoS One. 11(5): e0154760. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Sridhar S, Luedtke A, Langevin E, Zhu M, Bonaparte M, et al. 2018. Effect of dengue serostatus on dengue vaccine safety and efficacy. N Engl J Med. 379(4): 327–340. ArticlePubMed

- St John AL, Rathore APS, Raghavan B, Ng ML, Abraham SN. 2013. Contributions of mast cells and vasoactive products, leukotrienes and chymase, to dengue virus-induced vascular leakage. eLife. 2: e00481. PubMedPMC

- Sugrue RJ, Fu J, Howe J, Chan YC. 1997. Expression of the dengue virus structural proteins in Pichia pastoris leads to the generation of virus-like particles. J Gen Virol. 78(Pt 8): 1861–1866. ArticlePubMed

- Sun P, Jani V, Johnson A, Cheng Y, Nagabhushana N, et al. 2021. T cell and memory B cell responses in tetravalent DNA, tetravalent inactivated and tetravalent live-attenuated prime-boost dengue vaccines in rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 39(51): 7510–7520. ArticlePubMed

- Sun J, Li M, Wang Y, Hao P, Jin X. 2017. Elaboration of tetravalent antibody responses against dengue viruses using a subunit vaccine comprised of a single consensus dengue envelope sequence. Vaccine. 35(46): 6308–6320. ArticlePubMed

- Sundaram AK, Ewing D, Blevins M, Liang Z, Sink S, et al. 2020. Comparison of purified psoralen-inactivated and formalin-inactivated dengue vaccines in mice and nonhuman primates. Vaccine. 38(17): 3313–3320. ArticlePubMed

- Suphatrakul A, Yasanga T, Keelapang P, Sriburi R, Roytrakul T, et al. 2015. Generation and preclinical immunogenicity study of dengue type 2 virus-like particles derived from stably transfected mosquito cells. Vaccine. 33(42): 5613–5622. ArticlePubMed

- Suzarte E, Gil L, Valdés I, Marcos E, Lazo L, et al. 2015. A novel tetravalent formulation combining the four aggregated domain III-capsid proteins from dengue viruses induces a functional immune response in mice and monkeys. Int Immunol. 27(8): 367–379. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Suzarte E, Marcos E, Gil L, Valdés I, Lazo L, et al. 2014. Generation and characterization of potential dengue vaccine candidates based on domain III of the envelope protein and the capsid protein of the four serotypes of dengue virus. Arch Virol. 159(7): 1629–1640. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Tang YX, Jiang LF, Zhou JM, Yin Y, Yang XM, Liu WQ, et al. 2012. Induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses by dengue virus type 1 virus-like particles prepared from Pichia pastoris. Chin Med J (Engl). 125(11): 1986–1992. PubMed

- Taslem Mourosi J, Awe A, Jain S, Batra H. 2022. Nucleic acid vaccine platform for DENGUE and ZIKA flaviviruses. Vaccines (Basel). 10(6).

- Taylor-Robinson A. 2016. A putative fifth serotype of dengue-potential implications for diagnosis, therapy, and vaccine design. Int J Clin Med Microbiol. 1(101): 1–2. Article

- TEAM W, Immunization VA, BI. 2024. Vaccines and immunization: Dengue. Retrieved 10 May 2024 from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/dengue-vaccines

- Thomas SJ. 2023. Is new dengue vaccine efficacy data a relief or cause for concern? NPJ Vaccines. 8(1): 55.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Thoresen D, Matsuda K, Urakami AM, et al. 2024. A tetravalent dengue virus-like particle vaccine induces high levels of neutralizing antibodies and reduces dengue replication in non-human primates. J Virol. 98(5): e0023924. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Tomczyk T, Orzechowska B. 2013. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) as a vaccine vector for immunization against viral infections. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 67: 1345–1358. ArticlePubMed

- Tricou V, Sáez-Llorens X, Yu D, et al. 2020. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children aged 2-17 years: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 395(10234): 1434–1443. ArticlePubMed

- Tricou V, Yu D, Reynales H, et al. 2024. Long-term efficacy and safety of a tetravalent dengue vaccine (TAK-003): 4·5-year results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 12(2): e257–e270. ArticlePubMed

- Tripathi L, Mani S, Raut R, et al. 2015. Pichia pastoris-expressed dengue 3 envelope-based virus-like particles elicit predominantly domain III-focused high titer neutralizing antibodies. Front Microbiol. 6: 1005.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Trung DT, Wills B. 2010. Systemic vascular leakage associated with dengue infections - The clinical perspective. In Rothman AL. (ed.), Dengue Virus, pp. 57–66, Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Tully D, Griffiths CL. 2021. Dengvaxia: the world’s first vaccine for prevention of secondary dengue. Therapeutic Advances in Vaccines and Immunotherapy. 9: 25151355211015839.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Urakami A, Ngwe Tun MM, Moi ML, Sakurai A, Ishikawa M, et al. 2017. An envelope-modified tetravalent dengue virus-like particle vaccine has implications for flavivirus vaccine design. J Virol. 91(23): e01181–17. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Utomo DIS, Pambudi S, Park EY. 2022. Humoral immune response induced with dengue virus-like particles serotypes 1 and 4 pro-duced in silkworm. AMB Express. 12(1): 8.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-García JL, Rivera DM, Cunha R, et al. 2015. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children in Latin America. N Engl J Med. 372(2): 113–123. ArticlePubMed

- Wang TT, Sewatanon J, Memoli MJ, Wrammert J, Bournazos SK, et al. 2017. IgG antibodies to dengue enhanced for FcγRIIIA binding determine disease severity. Science. 355(6323): 395–398. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Weiskopf D, Angelo MA, Bangs DJ, Sidney J, Paul S, et al. 2015. The human CD8+ T cell responses induced by a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine are directed against highly conserved epitopes. J Virol. 89(1): 120–128. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Weiskopf D, Angelo MA, de Azeredo EL, Sidney J, Greenbaum JA, et al. 2013. Comprehensive analysis of dengue virus-specific responses supports an HLA-linked protective role for CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110(22): E2046–2053. ArticlePubMedPMC

- White LJ, Parsons MM, Whitmore AC, Williams BM, Silva AD, et al. 2007. An immunogenic and protective alphavirus replicon particle-based dengue vaccine overcomes maternal antibody interference in weanling mice. J Virol. 81(19): 10329–10339. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- White LJ, Sariol CA, Mattocks MD, B WWMP, Yingsiwaphat V, et al. 2013. An alphavirus vector-based tetravalent dengue vaccine induces a rapid and protective immune response in macaques that differs qualitatively from immunity induced by live virus infection. J Virol. 87(6): 3409–3424. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Whitehead SS. 2016. Development of TV003/TV005, a single dose, highly immunogenic live attenuated dengue vaccine; what makes this vaccine different from the Sanofi-Pasteur CYD™ vaccine? Expert Rev Vaccines. 15(4): 509–517. ArticlePubMedPMC

- WHO. 2024 May 15. WHO prequalifies new dengue vaccine. Retrieved 15 May 2024 from https://www.who.int/zh/news/item/15-05-2024-who-prequalifies-new-dengue-vaccine

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. 2009. In Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control: New Edition. World Health Organization

- Wilken L, Stelz S, Agac A, Sutter G, Prajeeth CK, et al. 2023. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing a glycosylation mutant of dengue virus NS1 induces specific antibody and T-cell responses in mice. Vaccines (Basel). 11(4): 714.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Williams M, Ewing D, Blevins M, Sun P, Sundaram AK, et al. 2019. Enhanced immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tetravalent dengue DNA vaccine using electroporation and intradermal delivery. Vaccine. 37(32): 4444–4453. ArticlePubMed

- Wollner CJ, Richner M, Hassert MA, Pinto AK, Brien JD, et al. 2021. A dengue virus serotype 1 mRNA-LNP vaccine elicits protective immune responses. J Virol. 95(12): e02482–20. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Wu SJ, Ewing D, Sundaram AK, Chen HW, Liang Z, et al. 2022. Enhanced immunogenicity of inactivated dengue vaccines by novel polysaccha-ride-based adjuvants in mice. Microorganisms. 10(5): 1034.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Yacoub S, Wertheim H, Simmons CP, Screaton G, Wills B. 2015. Microvascular and endothelial function for risk prediction in dengue: an observational study. Lancet. 385 Suppl 1: S102.ArticlePubMed

- Zhang S, Liang M, Gu W, Li C, Miao F, Wang X, Jin C, Zhang L, Zhang F, Zhang Q, Jiang L, Li M, Li D. 2011. Vaccination with dengue virus-like particles induces humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. Virol J. 8: 333.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Zhang M, Sun J, Li M, Jin X. 2020. Modified mRNA-LNP vaccines confer protection against experimental DENV-2 infection in mice. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 18: 702–712. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Zhang ZS, Yan YS, Weng YW, Huang HL, Li SQ, He S, Zhang JM. 2007. High-level expression of recombinant dengue virus type 2 envelope domain III protein and induction of neutralizing antibodies in BALB/C mice. J Virol Methods. 143(2): 125–131. ArticlePubMed

- Zhang Y, Zhang W, Ogata S, Clements D, Strauss JH, Baker TS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2004. Conformational changes of the flavivirus E glycoprotein. Structure. 12(9): 1607–1618. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Zheng X, Chen H, Wang R, Fan D, Feng K, Gao N, An J. 2017. Effective protection induced by a monovalent DNA vaccine against dengue virus (DV) serotype 1 and a bivalent DNA vaccine against DV1 and DV2 in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 7: 175.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Zheng Q, Fan D, Gao N, Chen H, Wang J, Ming Y, Li J, An J. 2011. Evaluation of a DNA vaccine candidate expressing prM-E-NS1 antigens of dengue virus serotype 1 with or without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in immunogenicity and protection. Vaccine. 29(4): 763–771. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- E protein inhibitors and host-directed therapies in dengue virus infection: perspectives on combination and complementary antiviral strategies

Ricardo Jiménez-Camacho, Carlos Noe Farfan-Morales, José De Jesús Bravo-Silva, Magda Lizbeth Benítez-Vega, Marcos Pérez-García, Jonathan Hernández-Castillo, Carlos Daniel Cordero-Rivera, Rosa María Del Ángel

Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery.2026; 21(1): 101. CrossRef - Dengue Fever Vaccines: Progress and Challenges

Alan L. Rothman, Heather Friberg

Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology .2026; 66(1): 129. CrossRef - A Capabilities, Opportunities, and Motivations behavioral analysis of healthcare professionals concerning dengue vaccination in selected countries from Latin America and Asia Pacific

Andrew Green, Alberta Di Pasquale, Eduardo Lopez-Medina

Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - A Multivalent Dengue Fusion Protein ΔcNS1–cEDIII–ΔnNS3 Confers Cross‐Serotype Protection and Durable Immunity in Mice

Mu‐Fan Pi, Wei‐Chiao Liao, Xin‐Yan Li, Miao‐Huei Cheng, Chu‐En Tsai, Yen‐Chung Lai, Hsing‐Han Lin, Yung‐Chun Chuang, Chin‐Kai Tseng, Yee‐Shin Lin, Chih‐Peng Chang, Tzong‐Shiann Ho, Guan‐Da Syu, Trai‐Ming Yeh, Jen‑Ren Wang, Justin Jang Hann Chu, Chia‐Yi Yu

Journal of Medical Virology.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Pharmaceutical design of mRNA vaccines for endemic infectious diseases: integrating antigen discovery with platform engineering

Shuaibu Abdullahi Hudu, Abdulgafar Alayiwola Jimoh

Clinical and Experimental Vaccine Research.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Role of c-ABL in DENV-2 Infection and Actin Remodeling in Vero Cells

Grace Paola Carreño-Flórez, Alexandra Milena Cuartas-López, Ryan L. Boudreau, Miguel Vicente-Manzanares, Juan Carlos Gallego-Gómez

International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2025; 26(9): 4206. CrossRef - Crystallographic Fragment Screening of the Dengue Virus Polymerase Reveals Multiple Binding Sites for the Development of Non-nucleoside Antiflavivirals

Manisha Saini, Jasmin C. Aschenbrenner, Francesc Xavier Ruiz, Ashima Chopra, Anu V. Chandran, Peter G. Marples, Blake H. Balcomb, Daren Fearon, Frank von Delft, Eddy Arnold

Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.2025; 68(17): 18356. CrossRef - Understanding the Diversity of Dengue Serotypes: Impacts on Public Health and Disease Control

Gopinath Ramalingam, Madhumitha Patchaiyappan, M. Arundadhi, Krishnapriya Subramani, A. Dhanasezhian, Sucila Thangam Ganesan

The Journal of Medical Research.2025; 11(4): 69. CrossRef - Dengue Fever Resurgence in Iran: An Integrative Review of Causative Factors and Control Strategies

Seyed Hassan Nikookar, Saeedeh Hoseini, Omid Dehghan, Mahmoud Fazelidinan, Ahmadali Enayati

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease.2025; 10(11): 309. CrossRef - Enhancement of viral infection by antibodies and consequences

Corentin Morvan, Magloire Pandoua Nekoua, Cyril Debuysschere, Enagnon Kazali Alidjinou, Didier Hober, Sebla Bulent Kutluay

Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Microbial Volatiles from Human Skin and Floral Nectar: Insufficiently Understood Adult Feeding Cues To Improve Odor-Based Traps for Aedes Vector Control

Simon Malassigné, Claire Valiente Moro, Patricia Luis

Journal of Chemical Ecology.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - An interpretable machine learning model for dengue detection with clinical hematological data

Izaz Ahmmed Tuhin, A.K.M.Fazlul Kobir Siam, Md Mahfuzur Rahman Shanto, Md Rajib Mia, Imran Mahmud, Apurba Ghosh

Healthcare Analytics.2025; 8: 100430. CrossRef

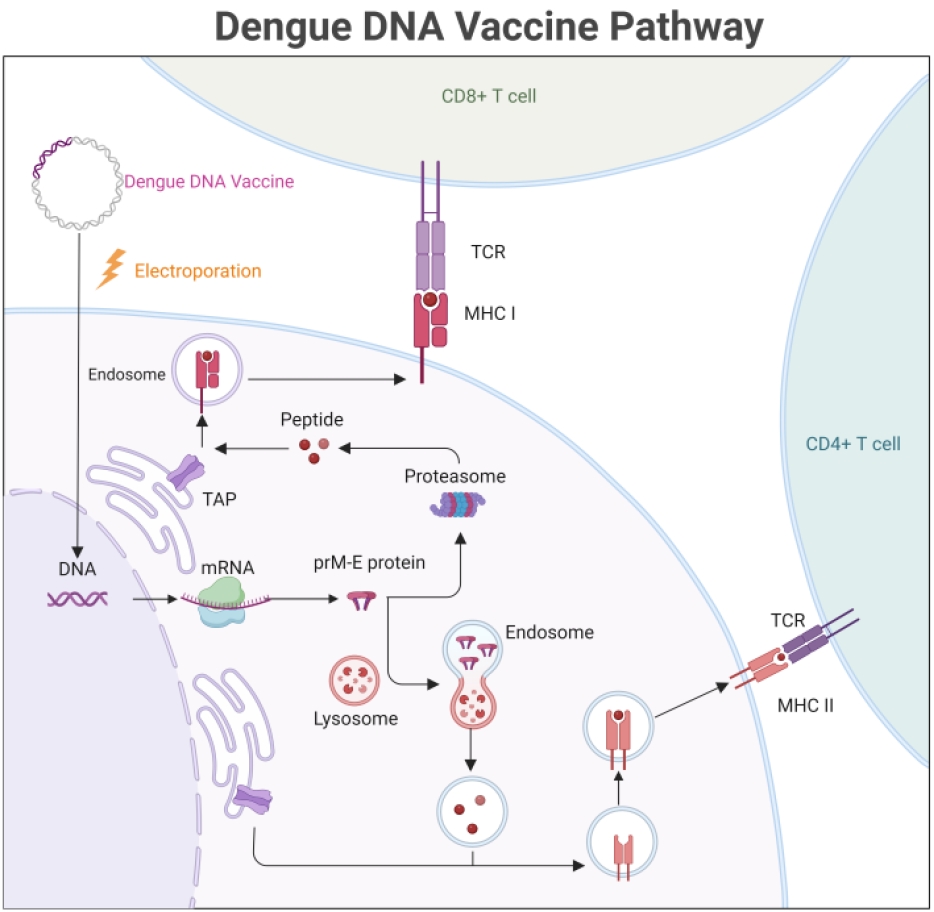

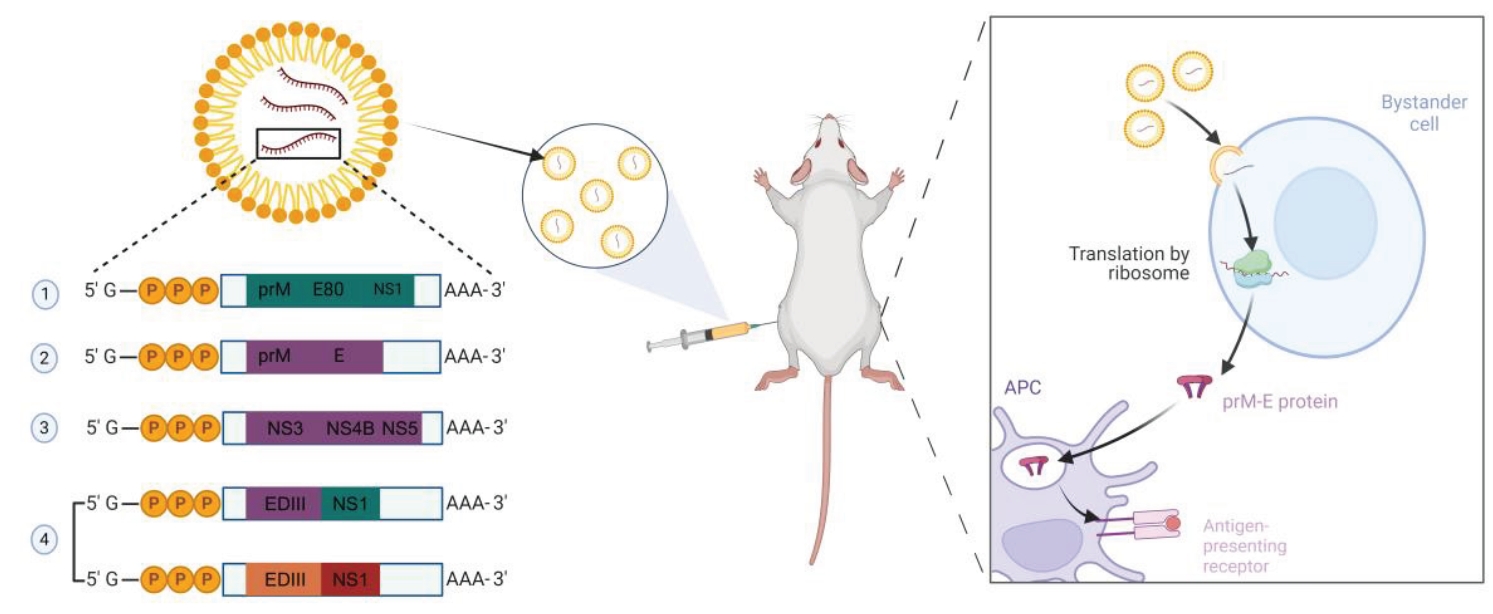

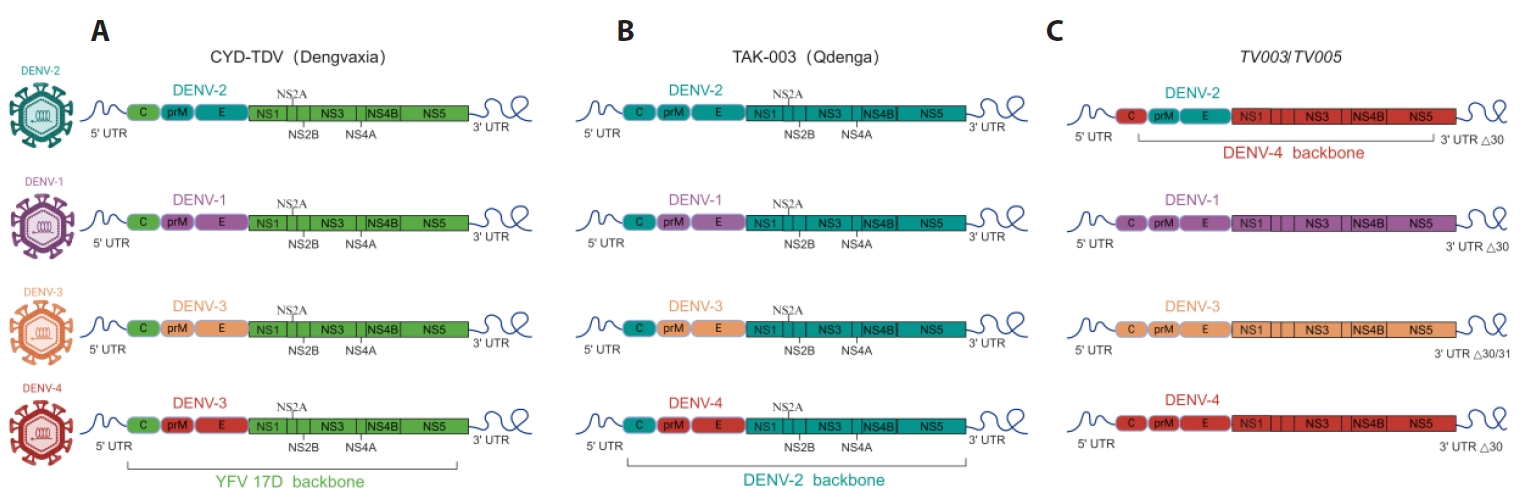

Fig. 1.

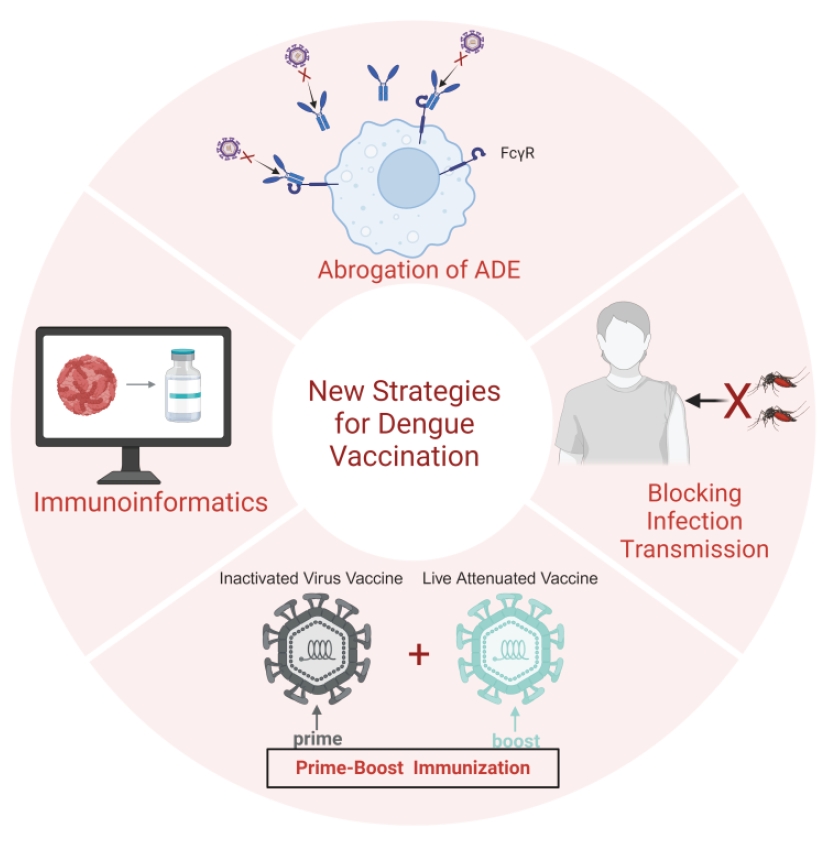

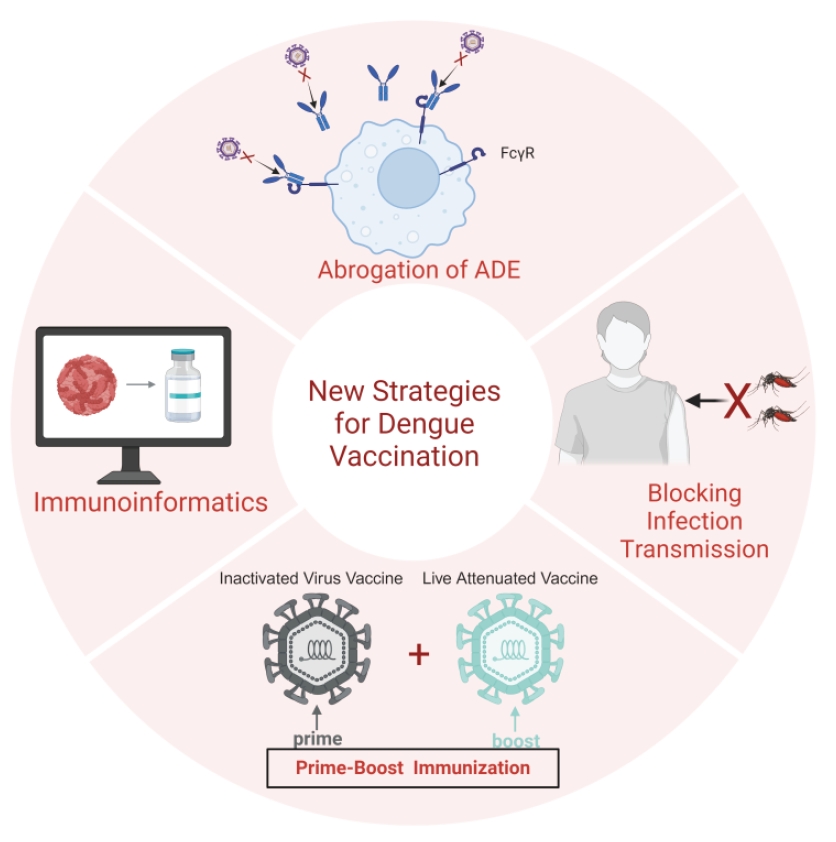

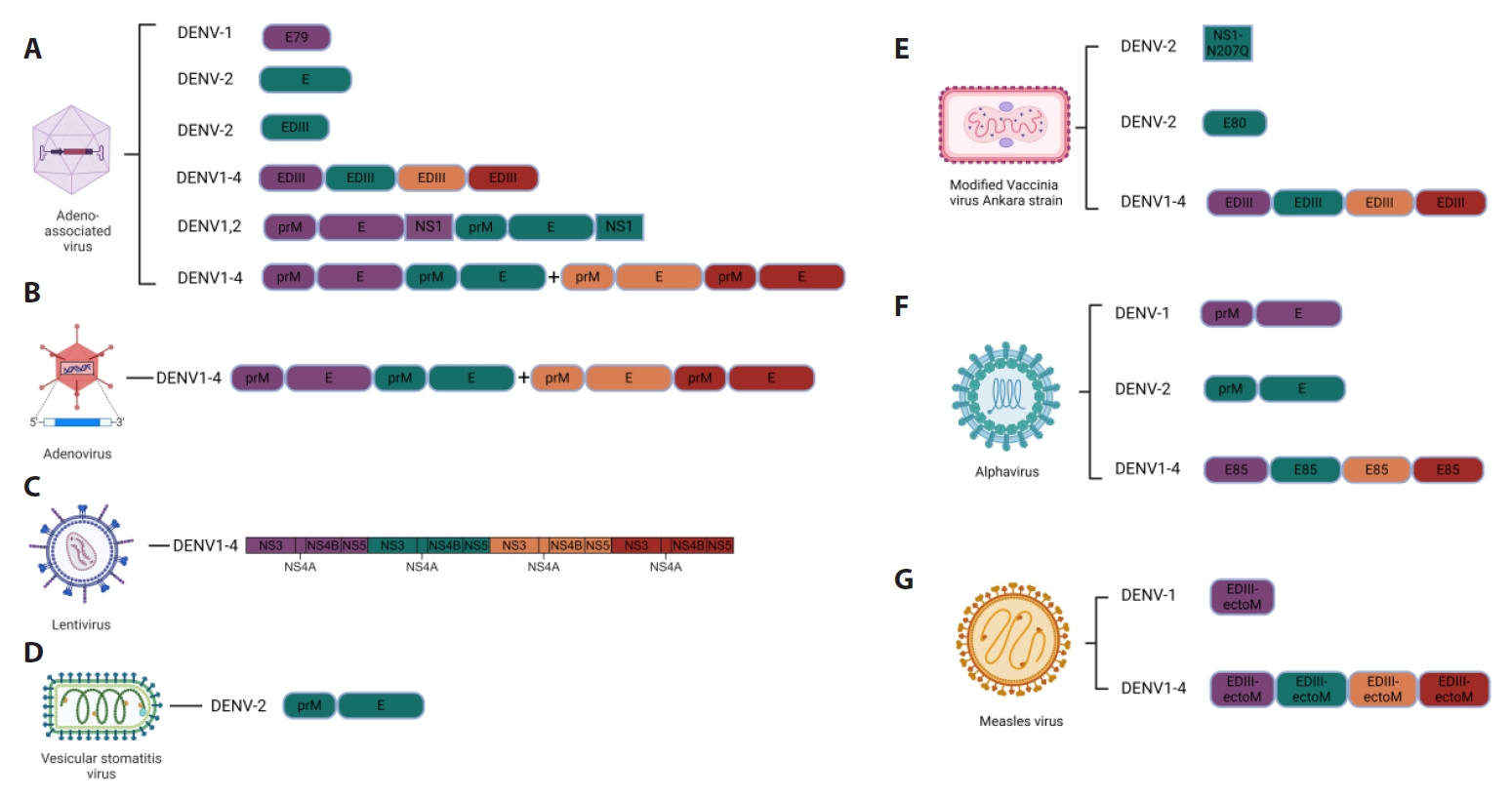

Fig. 2.

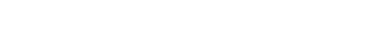

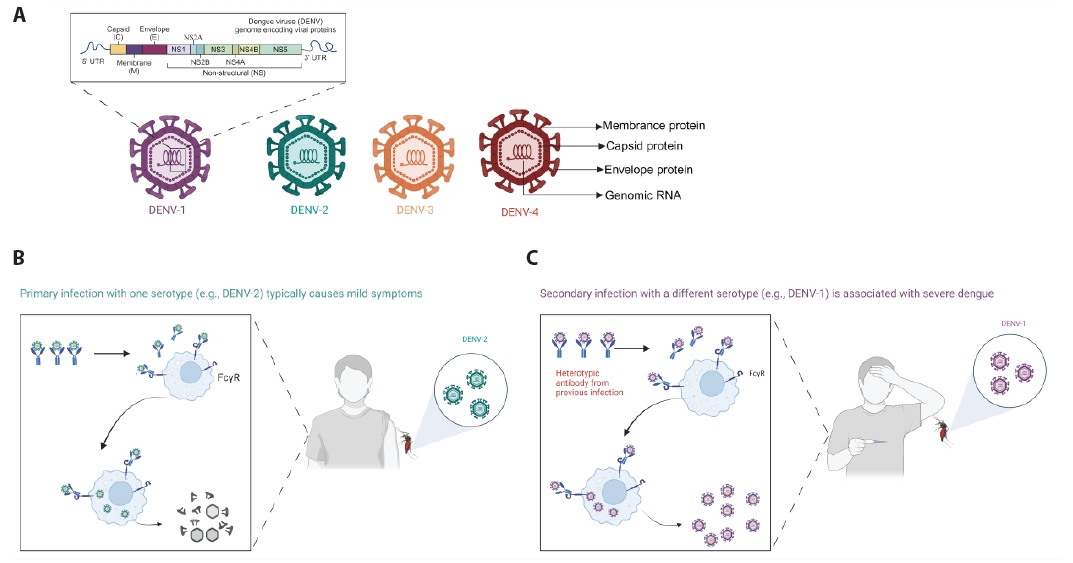

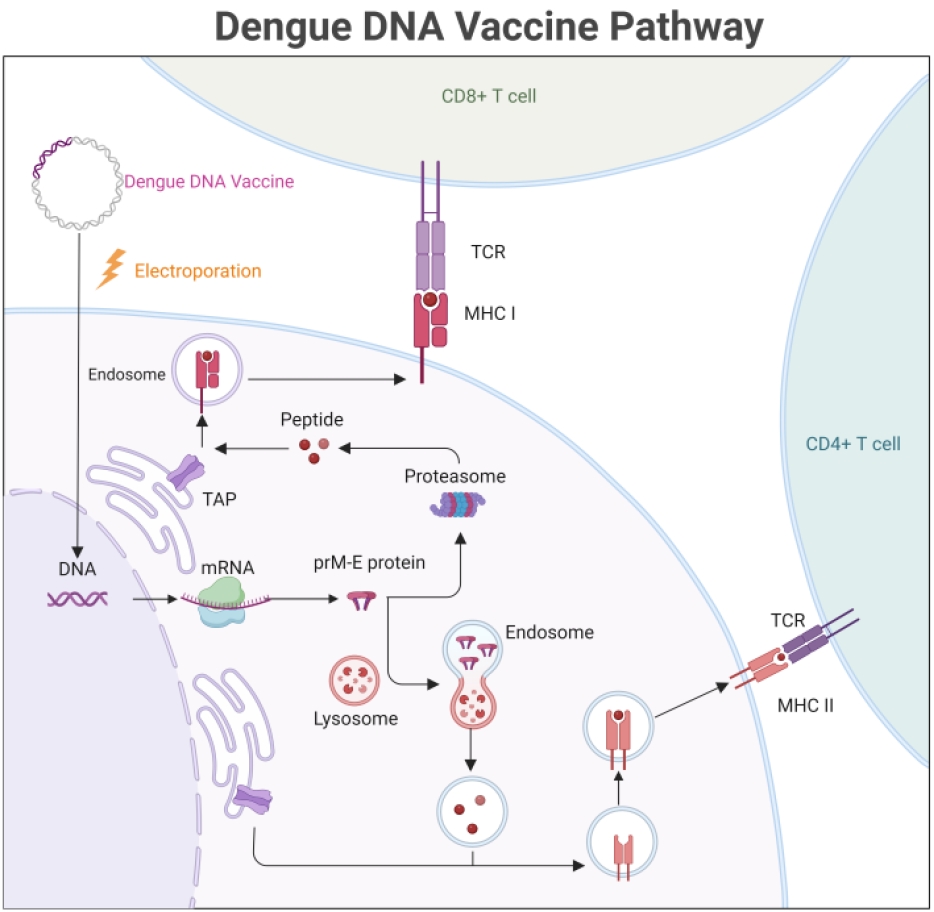

Fig. 3.

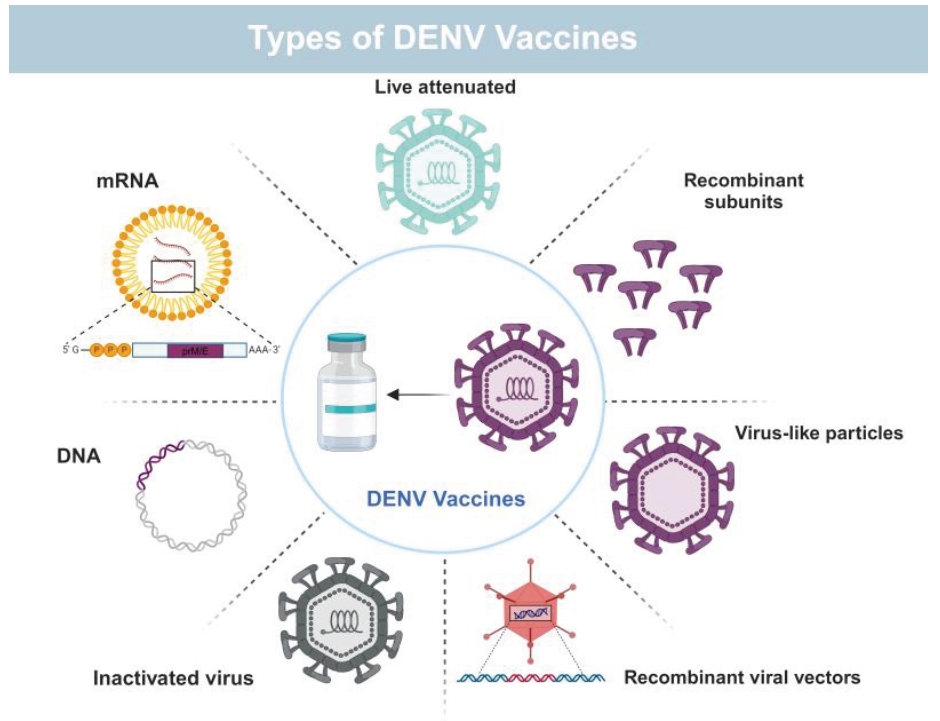

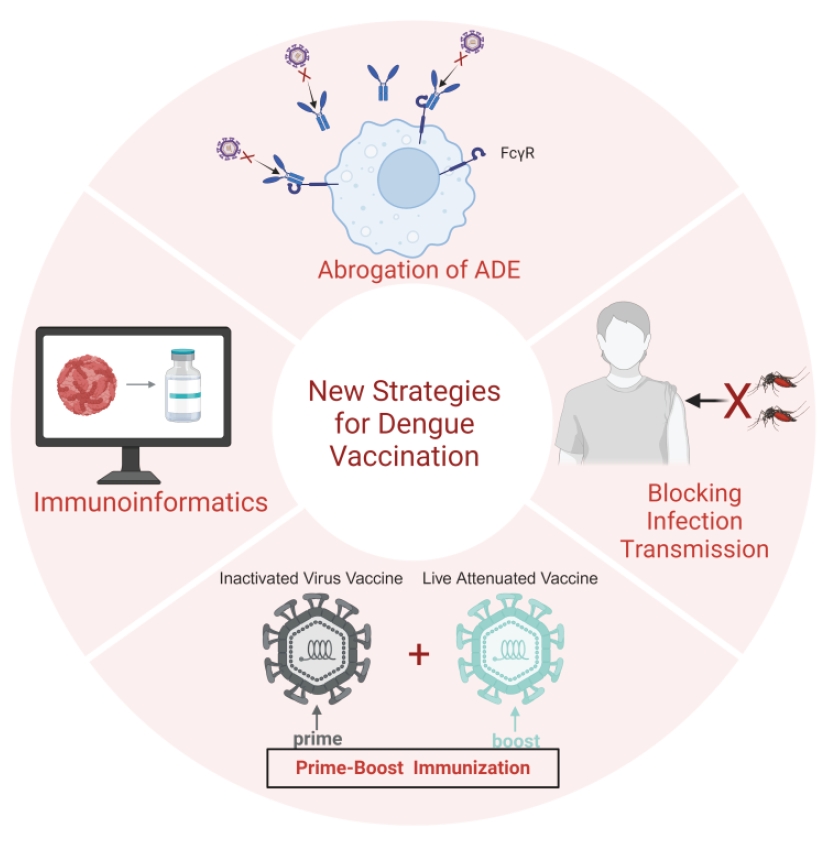

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

| Serotype | Inactivation method | Adjuvant | Animal models/Status | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | Formalin | Alum | Phase I: NCT01502735 | |

| DENV1-4 | Formalin | Alum, AS01E, AS03B | Phase I:NCT01666652,NCT01702857 | Diaz et al. ( |

| DENV1-4 | Formalin | AS03B | Phase I/II: NCT02421367 | |

| DENV1-4 | Formalin | Alum | Phase I: NCT02239614 |

| Serotype | Antigen | Expression system | Adjuvant | Animal models/Status | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV1-4 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | ISCOMATRIX™ adjuvant | Indian rhesus macaques | |

| DENV-1 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | Alhydrogel™ | Phase I: NCT00936429 | |

| DENV1-4 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | ISCOMATRIX™, Alhydrogel™ | Phase I: NCT01477580 | |

| DENV1-4 | E80 | Drosophila S2 cells | Alhydrogel™ | Phase I: NCT02450838 | |

| DENV-1 | DIII-P64k | E. coli | Freund's adjuvant | Macaca fascicularis, Rhesus monkeys | |

| DENV-2 | DIII-P64k | E. coli | Freund's adjuvant | Macaca fascicularis | |

| DENV1-4 | DIII-C | E. coli | Aluminum hydroxide | American green monkeys | Suzarte et al. ( |

| DENV2 | DIII-C+ ODNs (m2216, poly IC and 39M) | E. coli | Aluminum hydroxide | Vervet monkeys | |

| DENV1-4 | cEDIII | E. coli | Aluminum hydroxide | Macaca cyclopis |

| Serotype | Antigen | Expression system | Animal models | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | C-prM-E | P. pastoris | Rabbits | |

| DENV-1 | prM-E | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV1,2,3,4 | E ectodomain | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV1-2 | E | P. pastoris | BALB/c and AG129 mice | |

| DENV-2 | HBcAg-EDIII-2 | E. coli | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV-2 | HBcAg-EDIII-2 | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV1-4 | E | P. pastoris | BALB/c and AG129 mice | |

| DENV1-4 | EDIII-HBV S | P. pastoris | BALB/c, AG129, C57BL-6, C3H, Macaques | |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E | P. pastoris | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV1-4 | prM-EF108A | FreeStyle 293F cells | BALB/c mice,NIH Swiss outbred mice | |

| DENV1-4 | prM-EF108A | FreeStyle 293F cells | Cynomolgus monkeys,Common marmosets,AG129 mice | |

| DENV1-4 | C-prM-E | silkworm | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV-2 | prM-E | Mosquito cells | BALB/c mice,Cynomolgus macaques | |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E | 293T | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV-2 | C-prM-E+NS2B-NS3 | Expi293TM cells | BALB/c mice | |

| DENV-1 | C-prM-E+ΔNS5 NSP | Nicotiana benthamiana | BALB/c mice |

| Serotype | Antigen | Delivery mode | Animal models/Status | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV1-4 | prM-E | EP,i.d. | Macaca fascicularis monkeys | |

| DENV-1 | prM-E | Phase I: NCT00290147 | ||

| DENV1-4 | prM-E+Vaxfectin® | i.m. | Indian rhesus monkeys | |

| DENV1-4 | prM-E+Vaxfectin® | Phase I: NCT01502358 |

E.P., electroporation; i.m., intramuscular; i.d., intradermal

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

Table 4.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article