Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Volume 63(12); 2025 > Article

-

Full article

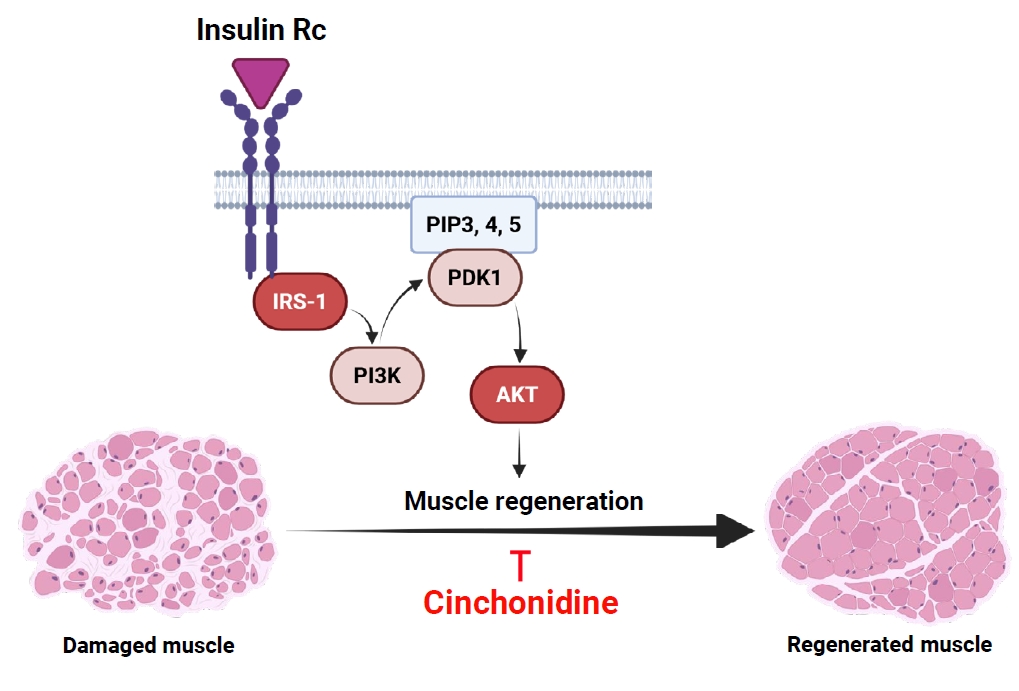

Cinchonidine induces muscle weakness by inhibiting insulin-mediated IRS-1-AKT signaling pathway - Mi Ran Byun1, Sang Hoon Joo1, Young-Suk Jung2,*, Joon-Seok Choi1,*

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2511017

Published online: December 17, 2025

1Department of Pharmacy, Daegu Catholic University, Gyeongsan 38430, Republic of Korea

2Department of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Research Institute for Drug Development, Pusan National University, Busan 46241, Republic of Korea

- *Correspondence Young-Suk Jung youngjung@pusan.ac.kr Joon-Seok Choi joonschoi@cu.ac.kr

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,011 Views

- 22 Download

ABSTRACT

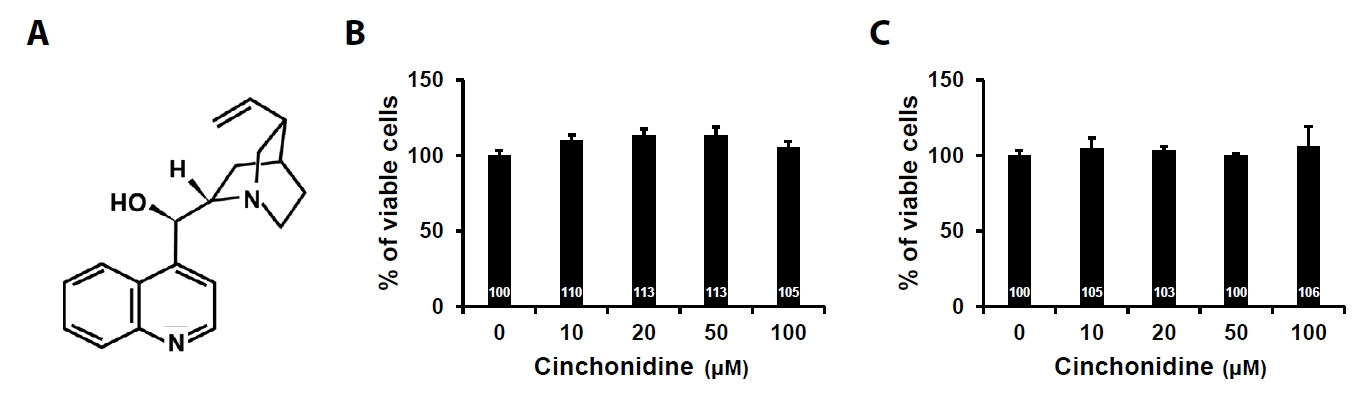

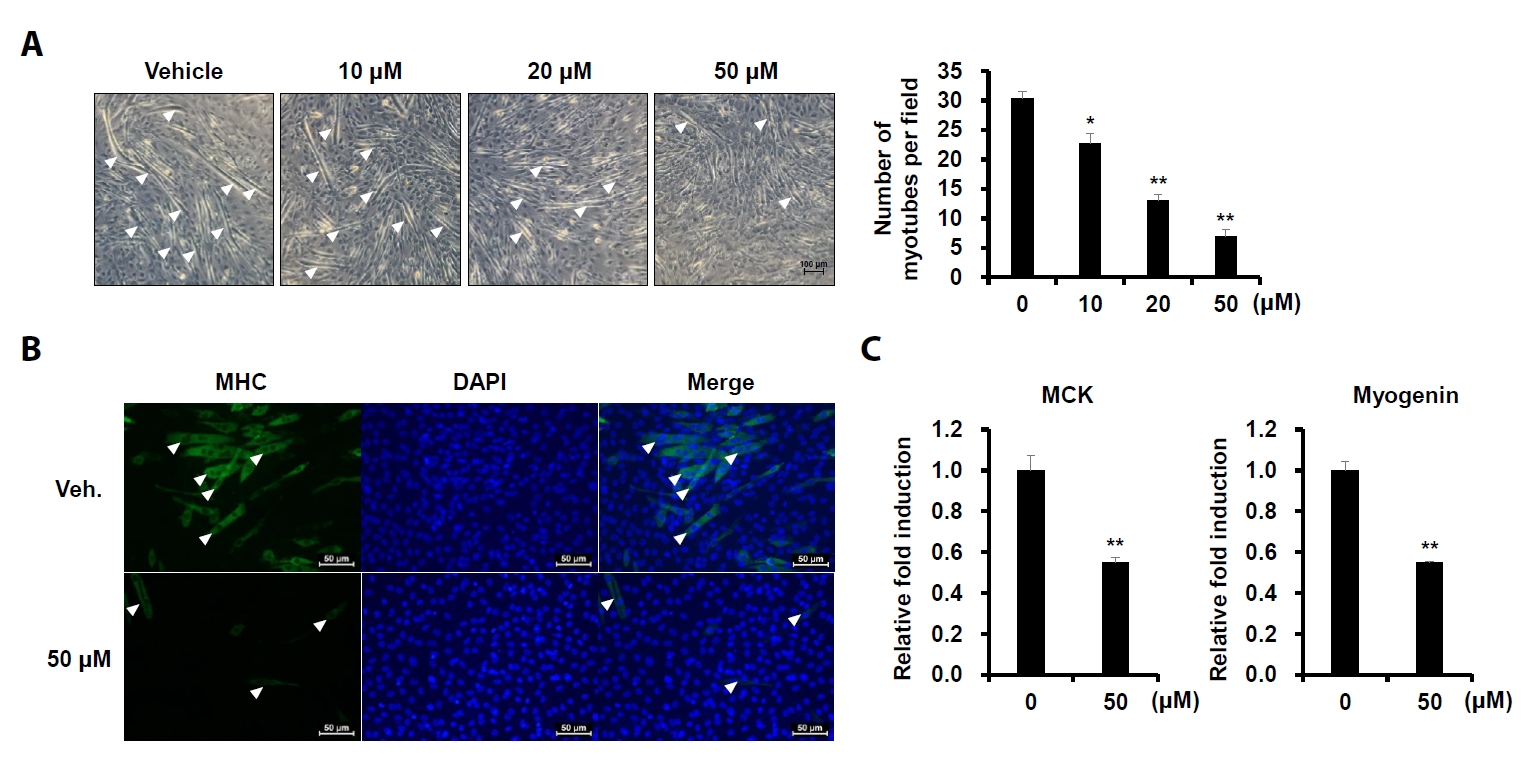

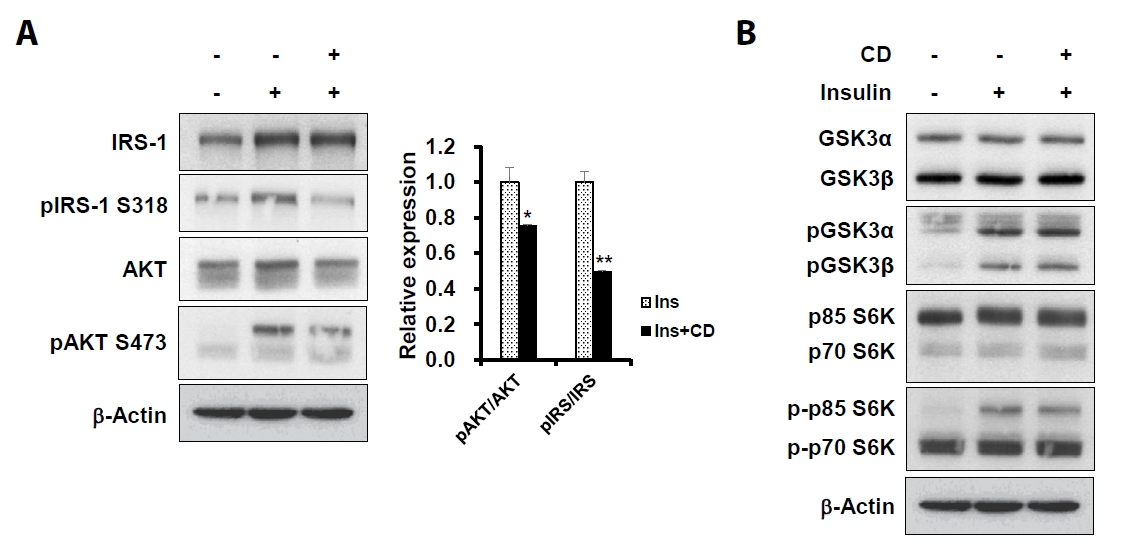

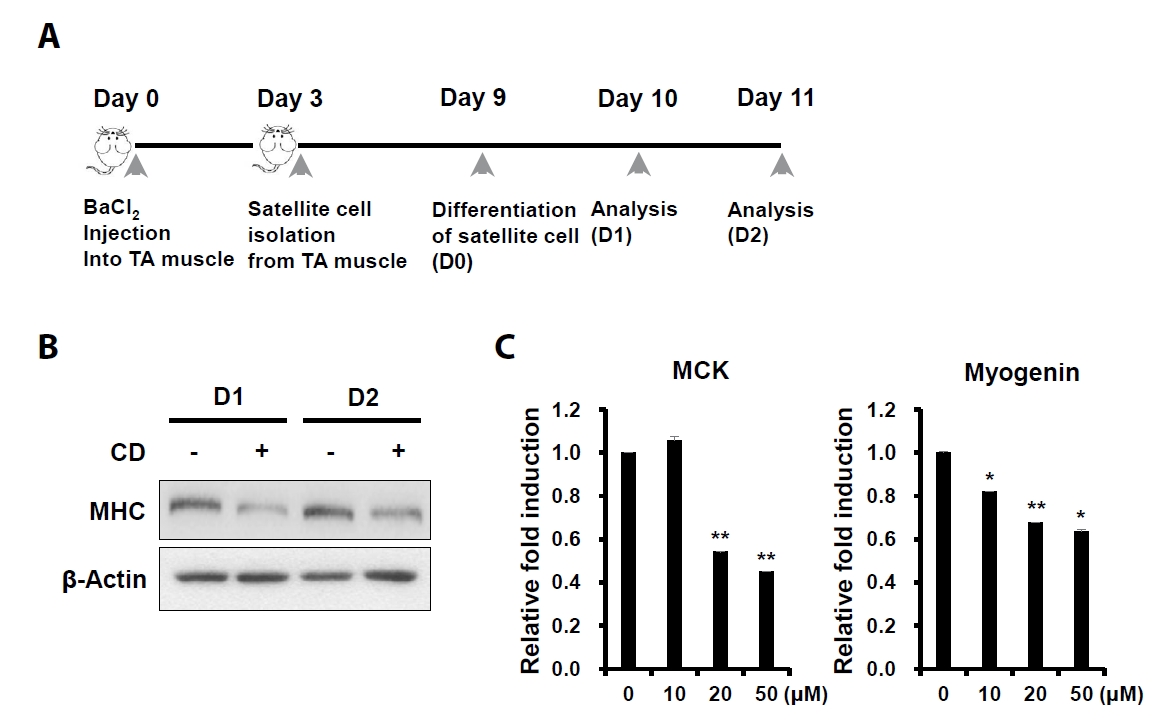

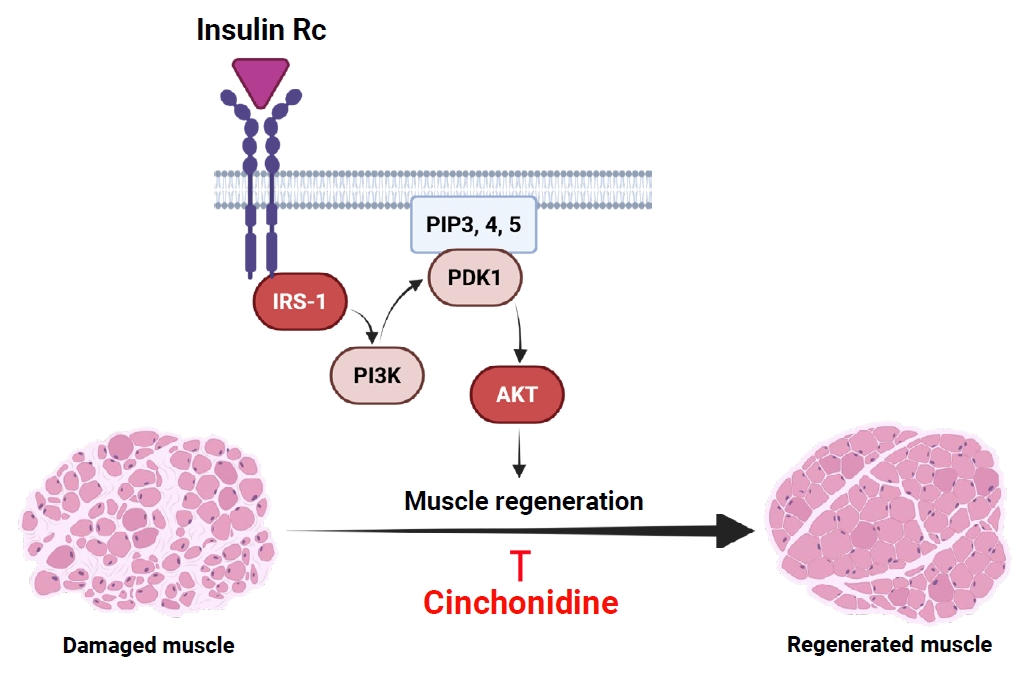

- Sarcopenia is an age-related condition marked by a reduction in muscle mass and strength, and it is associated with impaired muscle regeneration and differentiation. While diseases like cardiovascular and chronic liver disease can induce sarcopenia, there is limited evidence regarding the specific diseases and mechanisms responsible for its development. In skeletal muscle, the loss of muscle mass is accompanied by a decrease in myofilament proteins and the inhibition of muscle differentiation in satellite cells. Bioactive compounds obtained from natural products have been traditionally used as therapeutics for diverse conditions. In this report, we investigated the effect of cinchonidine (CD) extracted from Cinchona tree on muscle differentiation of mouse satellite cells, and myoblast cell lines. CD significantly inhibited muscle differentiation by suppressing myotube formation and gene expression of myogenesis markers. In addition, CD reduced muscle differentiation by blocking phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) during insulin-induced signal transduction. Therefore, the results show that CD, an antimalarial agent, inhibited muscle differentiation through the suppression of IRS-1 phosphorylation, suggesting that sarcopenia can be induced by CD.

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from Daegu Catholic University (20251185) in 2025. Also, Fig. 6 was created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Statements

All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Pusan National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (PNU-2023-0377).

- Abmayr SM, Pavlath GK. 2012. Myoblast fusion: lessons from flies and mice. Development. 139: 641–656. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Araki E, Lipes MA, Patti ME, Bruning JC, Haag B 3rd, et al. 1994. Alternative pathway of insulin signalling in mice with targeted disruption of the IRS-1 gene. Nature. 372: 186–190. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Basrani ST, Gavandi TC, Patil SB, Kadam NS, Yadav DV, et al. 2024. Hydroxychloroquine an antimalarial drug, exhibits potent antifungal efficacy against Candida albicans through multitargeting. J Microbiol. 62: 381–391. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Bentzinger CF, Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. 2012. Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 4: a008342.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Bielecka-Dabrowa A, Ebner N, Dos Santos MR, Ishida J, Hasenfuss G, et al. 2020. Cachexia, muscle wasting, and frailty in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Heart Fail. 22: 2314–2326. ArticlePubMedLink

- Birbrair A, Delbono O. 2015. Pericytes are essential for skeletal muscle formation. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 11: 547–548. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Bozzetti F. 2020. Chemotherapy-induced sarcopenia. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 21: 7.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Buckingham M. 2006. Myogenic progenitor cells and skeletal myogenesis in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 16: 525–532. ArticlePubMed

- Copps KD, Hancer NJ, Opare-Ado L, Qiu W, Walsh C, et al. 2010. Irs1 serine 307 promotes insulin sensitivity in mice. Cell Metab. 11: 84–92. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Curcio F, Ferro G, Basile C, Liguori I, Parrella P, et al. 2016. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: a multifactorial approach. Exp Gerontol. 85: 1–8. ArticlePubMed

- Degens H, Alway SE. 2006. Control of muscle size during disuse, disease, and aging. Int J Sports Med. 27: 94–99. ArticlePubMed

- Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Bardesono F, Freiburger M, Milano E, et al. 2022. Is sarcopenia associated with osteoporosis? A cross-sectional study of 262 women with hip fracture. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 58: 638–645. ArticlePubMedPMC

- He N, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Zhang S, Ye H. 2021. Relationship between sarcopenia and cardiovascular diseases in the elderly: an overview. Front Cardiovasc Med. 8: 743710.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Huo F, Liu Q, Liu H. 2022. Contribution of muscle satellite cells to sarcopenia. Front Physiol. 13: 892749.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Jo YJ, Lee HI, Kim N, Hwang D, Lee J, et al. 2021. Cinchonine inhibits osteoclast differentiation by regulating TAK1 and AKT, and promotes osteogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 236: 1854–1865. ArticlePubMedLink

- Jung SA, Choi M, Kim S, Yu R, Park T. 2012. Cinchonine prevents high-fat-diet-induced obesity through downregulation of adipogenesis and adipose inflammation. PPAR Res. 2012: 541204.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Kadi F, Ponsot E. 2010. The biology of satellite cells and telomeres in human skeletal muscle: effects of aging and physical activity. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 20: 39–48. Article

- Kadi F, Schjerling P, Andersen LL, Charifi N, Madsen JL, et al. 2004. The effects of heavy resistance training and detraining on satellite cells in human skeletal muscles. J Physiol. 558: 1005–1012. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Karim MR, Iqbal S, Mohammad S, Kim JH, Ling L, et al. 2024. Upgrading isoquercitrin concentration via submerge fermentation of mulberry fruit extract with edible probiotics to suppress gene targets for controlling kidney cancer and inflammation. J Microbiol. 62: 919–927. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Kuzuya M. 2024. Drug-related sarcopenia as a secondary sarcopenia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 24: 195–203. ArticlePubMed

- Marabita M, Baraldo M, Solagna F, Ceelen JJM, Sartori R, et al. 2016. S6K1 is required for increasing skeletal muscle force during hypertrophy. Cell Rep. 17: 501–513. ArticlePubMed

- Massimino E, Izzo A, Riccardi G, Della Pepa G. 2021. The impact of glucose-lowering drugs on sarcopenia in type 2 diabetes: current evidence and underlying mechanisms. Cells. 10: 1958.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Mesinovic J, Scott D. 2019. Sarcopenia and diabetes mellitus: evidence for a bi-directional relationship. Eur Geriatr Med. 10: 677–680. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Mesinovic J, Zengin A, De Courten B, Ebeling PR, Scott D. 2019. Sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional relationship. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 12: 1057–1072. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Miki H, Yamauchi T, Suzuki R, Komeda K, Tsuchida A, et al. 2001. Essential role of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and IRS-2 in adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 21: 2521–2532. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Mithal A, Bonjour JP, Boonen S, Burckhardt P, Degens H, et al. 2013. Impact of nutrition on muscle mass, strength, and performance in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 24: 1555–1566. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Pan Y, Xu J. 2022. Association between muscle mass, bone mineral density and osteoporosis in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 13: 351–358. ArticlePubMedLink

- Pedrosa MB, Barbosa S, Vitorino R, Ferreira R, Moreira-Gonçalves D, et al. 2023. Chemotherapy-induced molecular changes in skeletal muscle. Biomedicines. 11: 905.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Relaix F, Bencze M, Borok MJ, Der Vartanian A, Gattazzo F, et al. 2021. Perspectives on skeletal muscle stem cells. Nat Commun. 12: 692.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Rosenberg IH. 1997. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 127: 990S–991S. ArticlePubMed

- Ruiz-Mesia L, Ruiz-Mesía W, Reina M, Martínez-Diaz R, de Inés C, et al. 2005. Bioactive Cinchona alkaloids from Remijia peruviana. J Agric Food Chem. 53: 1921–1926. ArticlePubMed

- Schiaffino S, Mammucari C. 2011. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: insights from genetic models. Skelet Muscle. 1: 4.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Shah BH, Nawaz Z, Virani SS, Ali IQ, Saeed SA, et al. 1998. The inhibitory effect of cinchonine on human platelet aggregation due to blockade of calcium influx. Biochem Pharmacol. 56: 955–960. ArticlePubMed

- Sun XJ, Rothenberg P, Kahn CR, Backer JM, Araki E, et al. 1991. Structure of the insulin receptor substrate IRS-1 defines a unique signal transduction protein. Nature. 352: 73–77. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Sun XJ, Wang LM, Zhang Y, Yenush L, Myers MG Jr, et al. 1995. Role of IRS-2 in insulin and cytokine signalling. Nature. 377: 173–177. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Tang D, Wang X, Wu J, Li Y, Li C, et al. 2023. Cinchonine and cinchonidine alleviate cisplatin-induced ototoxicity by regulating PI3K-AKT signaling. CNS Neurosci Ther. 30: e14403. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Van Gerrewey T, Chung HS. 2024. MAPK Cascades in plant microbiota structure and functioning. J Microbiol. 62: 231–248. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Volpi E, Nazemi R, Fujita S. 2004. Muscle tissue changes with aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 7: 405–410. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Walston JD. 2012. Sarcopenia in older adults. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 24: 623–627. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Warhurst DC. 1981. Cinchona alkaloids and malaria. Lancet. 318: 1346.Article

- Weigert C, Kron M, Kalbacher H, Pohl AK, Runge H, et al. 2008. Interplay and effects of temporal changes in the phosphorylation state of serine-302, -307, and -318 of insulin receptor substrate-1 on insulin action in skeletal muscle cells. Mol Endocrinol. 22: 2729–2740. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Wong CY, Al-Salami H, Dass CR. 2020. C2C12 cell model: its role in understanding of insulin resistance at the molecular level and pharmaceutical development at the preclinical stage. J Pharm Pharmacol. 72: 1667–1693. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Yeung SSY, Reijnierse EM, Pham VK, Trappenburg MC, Lim WK, et al. 2019. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10: 485–500. ArticlePubMedPMCLink

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

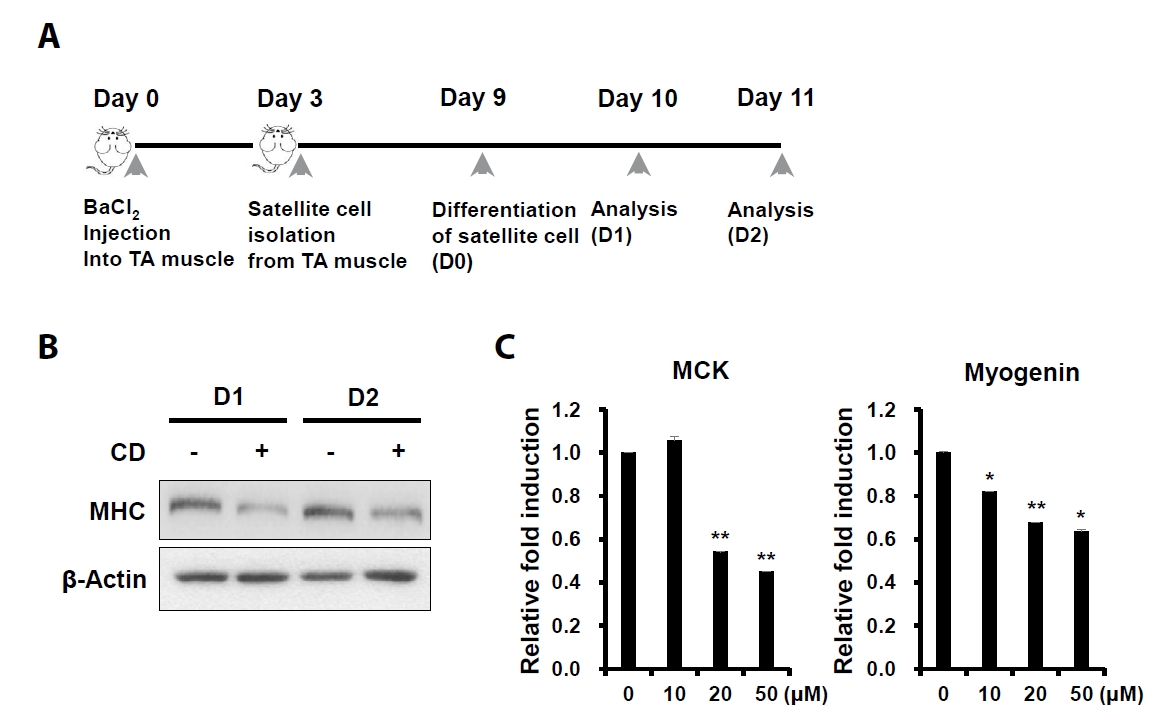

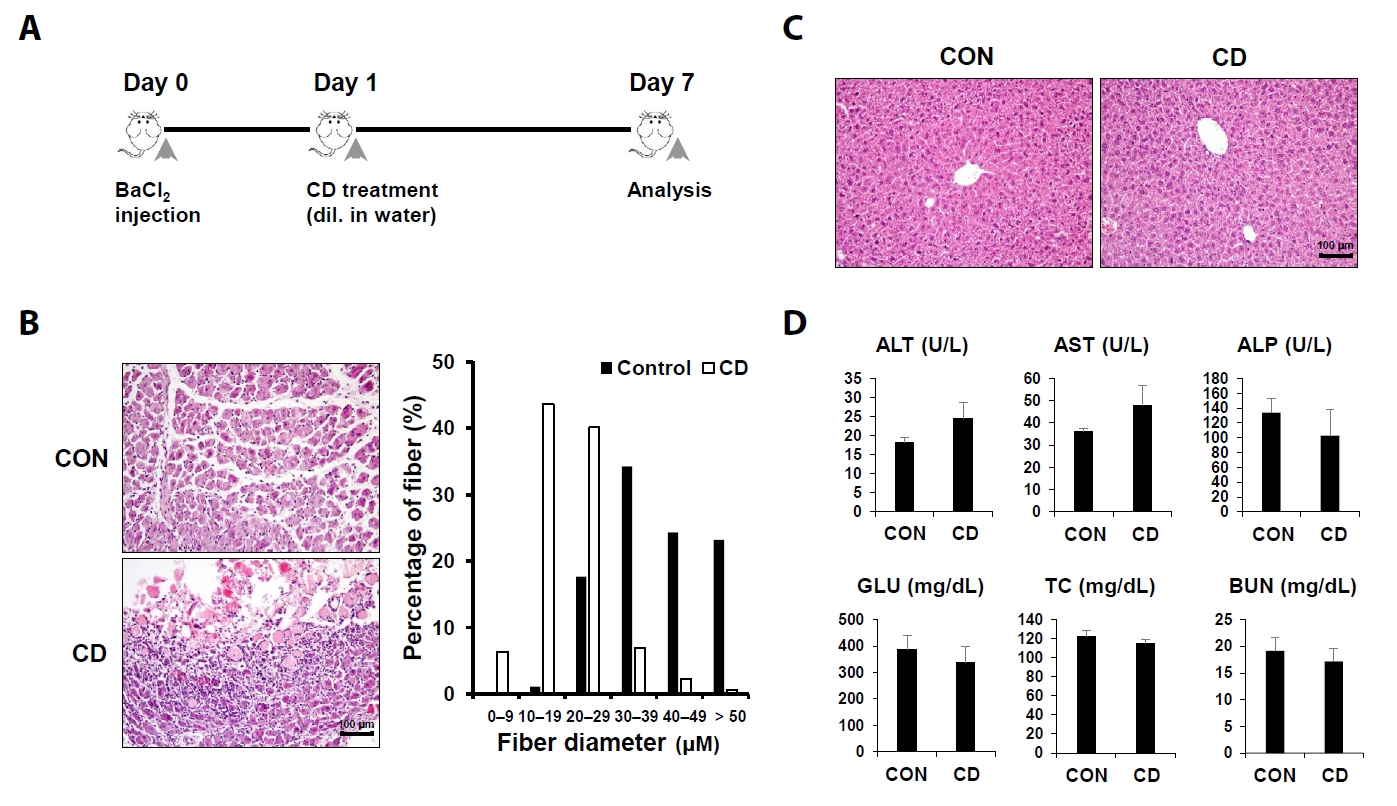

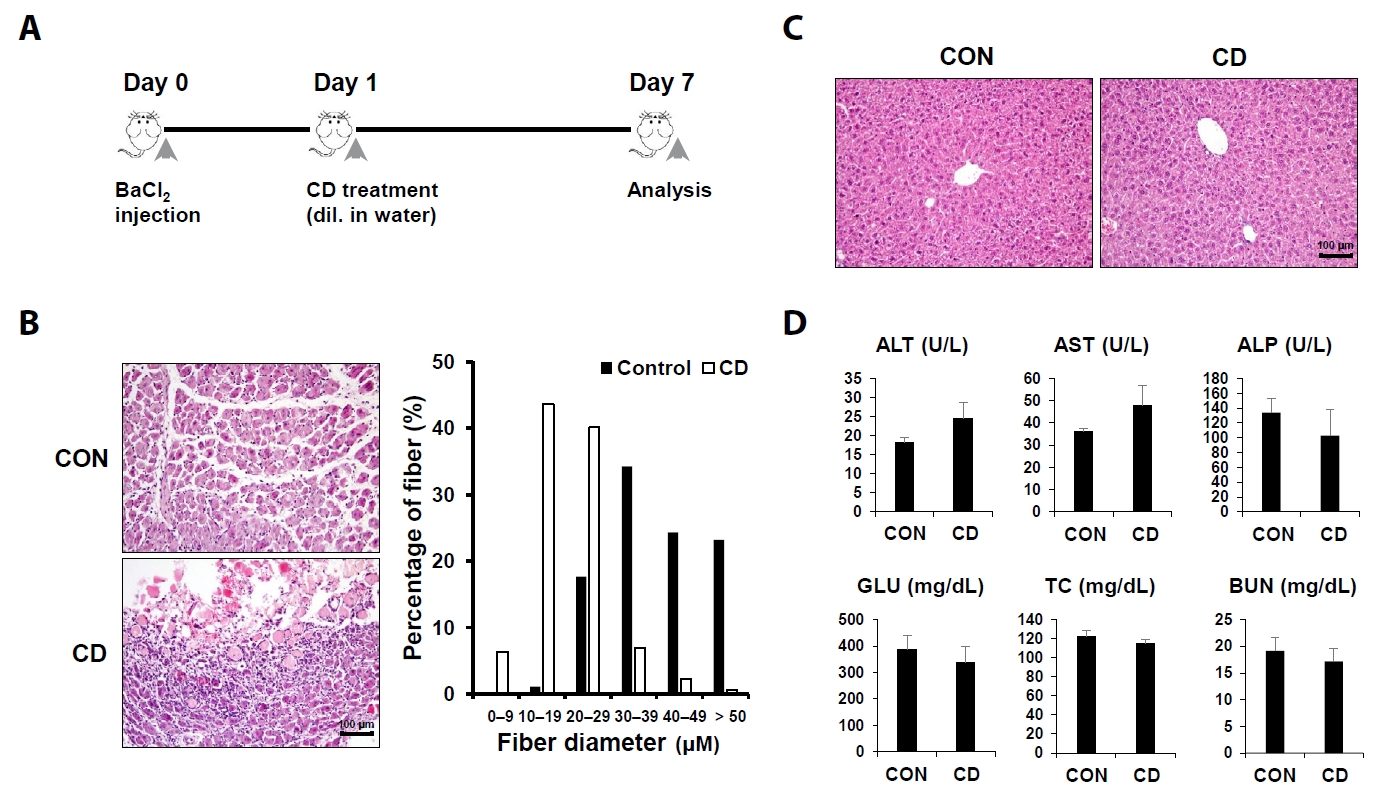

Fig. 1.

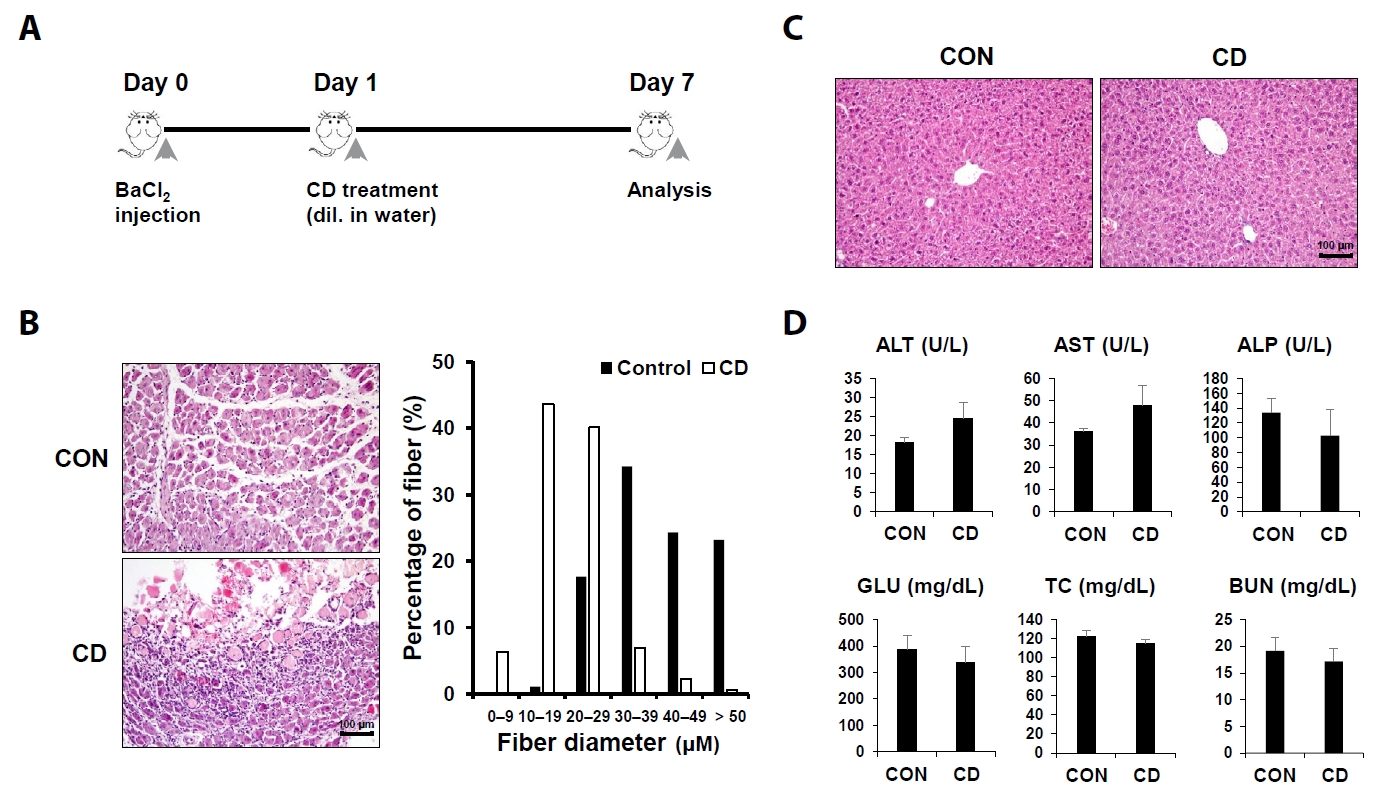

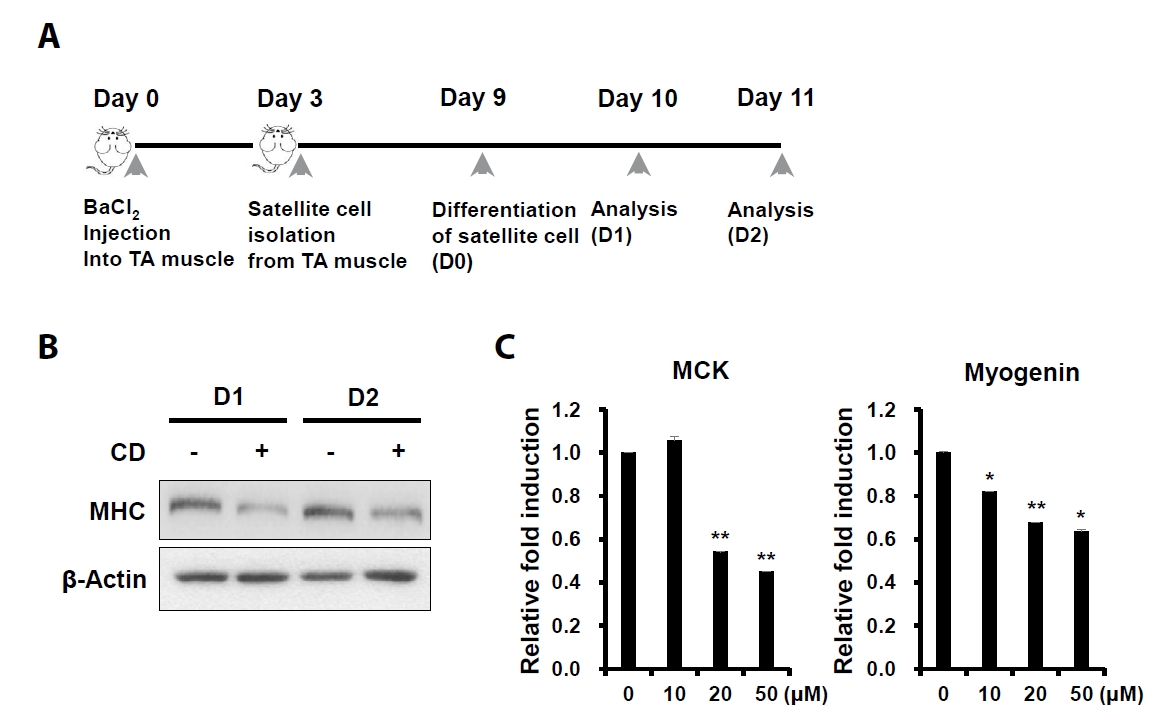

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

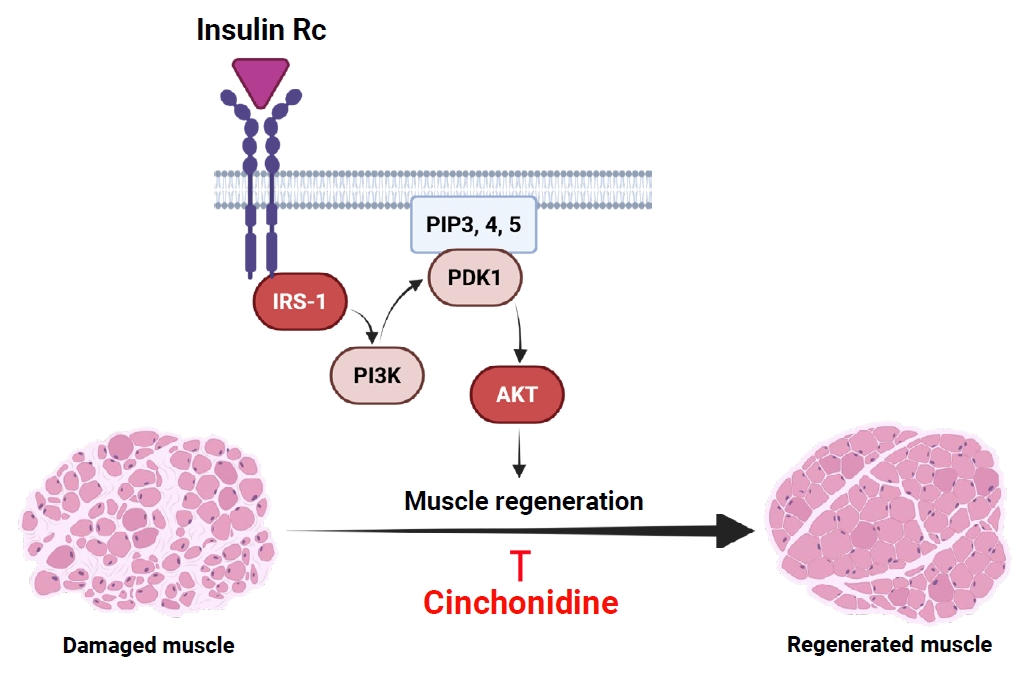

Fig. 6.

| Primer | Sequences |

|---|---|

| MCK-F | 5'-CACCTCCACAGCACAGACAG-3' |

| MCK-R | 5'-ACCTTGGCCATGTGATTGTT-3' |

| Myogenin-F | 5'-CAACCAGGAGGAGCGAGACCTCCG-3' |

| Myogenin-R | 5'-AGGCGCTGTGGGATATGCATTCACT-3' |

| GAPDH-F | 5'-GCTTGTCATCAACGGGAAG-3' |

| GAPDH-R | 5'-GATGTTAGTGGGGTCTCG-3' |

Table 1.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article