Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Volume 64(1); 2026 > Article

-

Review

Obesity, skin disorders, and the microbiota: Unraveling a complex web - Yu Ri Woo, Hei Sung Kim*

-

Journal of Microbiology 2026;64(1):e2508007.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2508007

Published online: January 31, 2026

Department of Dermatology, Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul 06649, Republic of Korea

- *Correspondence Hei Sung Kim hazelkimhoho@gmail.com

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,217 Views

- 57 Download

- ABSTRACT

- Introduction

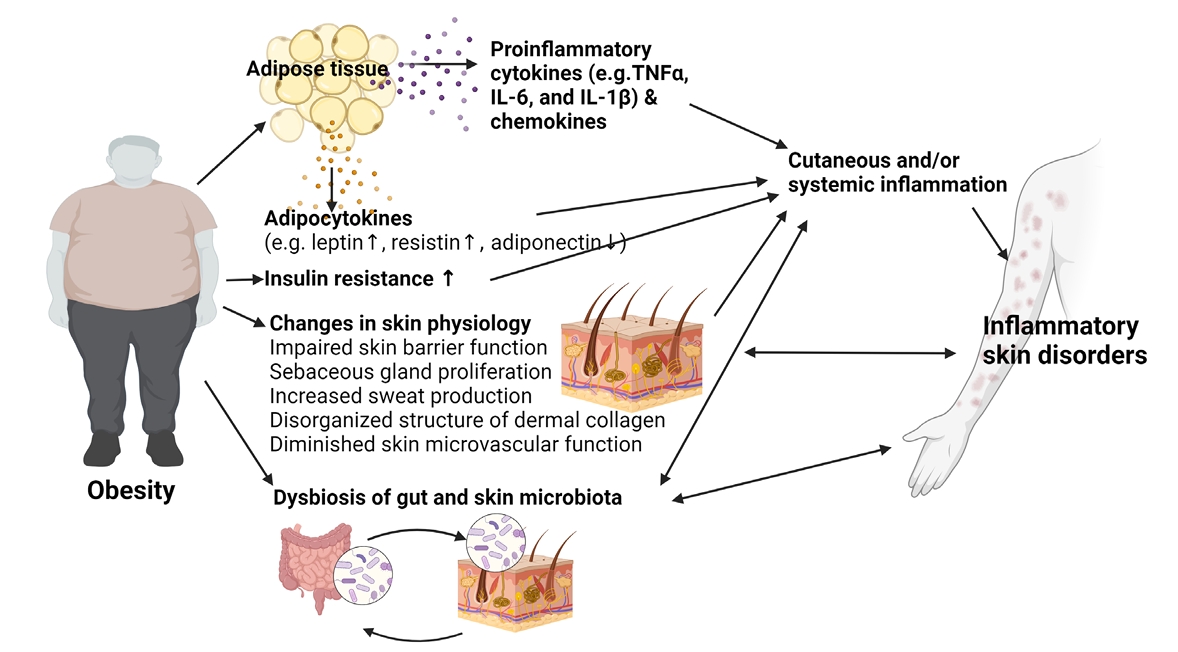

- Changes in Skin Physiology in Obese Patients

- Obesity and Inflammatory Skin Disorders

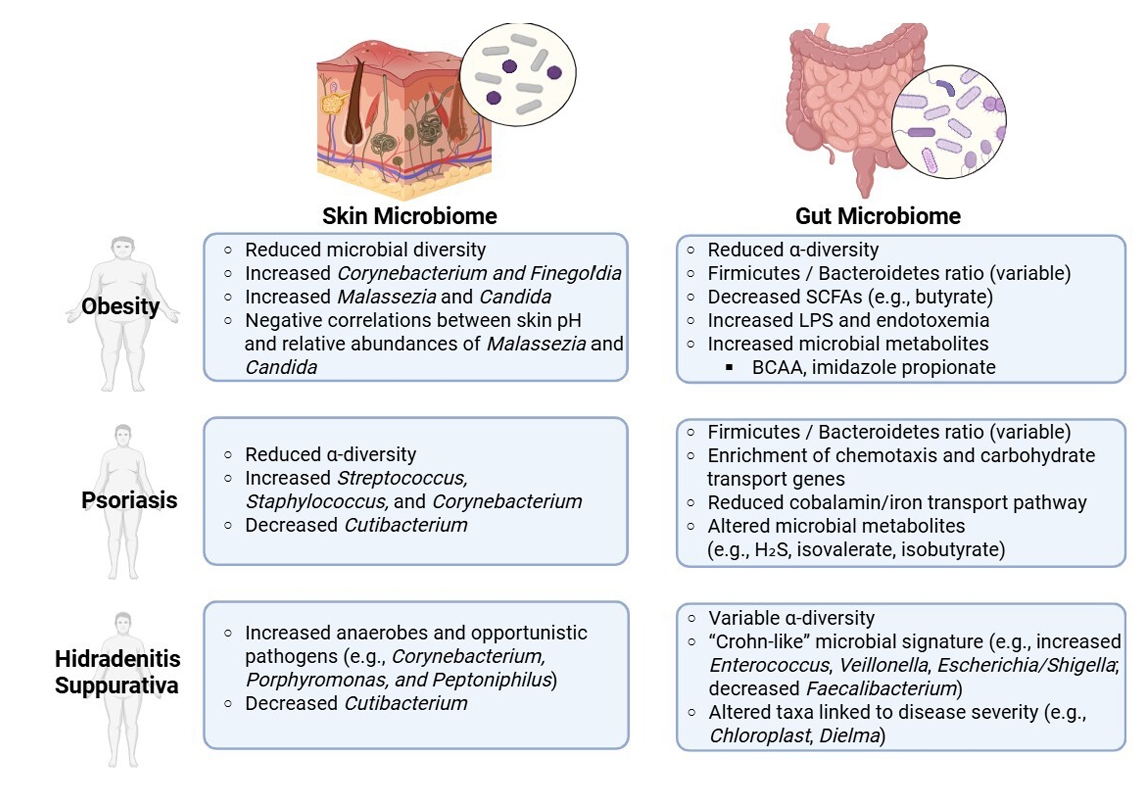

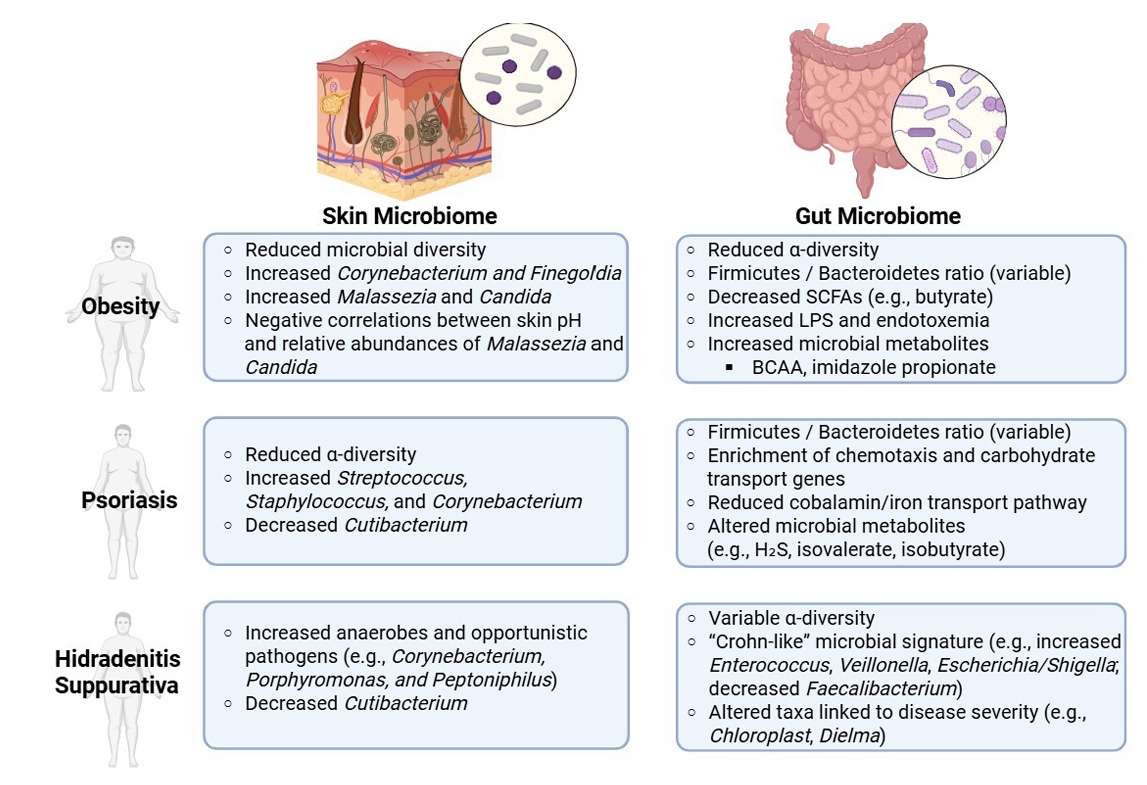

- Altered Skin Microbiota in Inflammatory Skin Disorders

- Altered Gut Microbiota in Obesity

- Altered Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Skin Disorders

- Therapeutic Approaches and Future Directions

- Limitations and Confounding Factors

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

ABSTRACT

- Obesity is increasingly recognized as a systemic pro-inflammatory condition that influences not only metabolic and cardiovascular health but also the development and exacerbation of cutaneous inflammatory diseases. This review examines the interplay between obesity, microbial dysbiosis, and two archetypal inflammatory skin disorders—hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and psoriasis. We highlight how obesity-induced changes in immune signaling, gut permeability, and microbiota composition—both in the gut and the skin—contribute to cutaneous inflammation. Special emphasis is placed on shared pathways such as the Th17/IL-23 and IL-22 signaling axes, adipokine imbalance, and microbial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids and lipopolysaccharides. The review critically evaluates the current literature, distinguishing preclinical insights from clinical evidence, and underscores the potential of microbiota-targeted therapies and metabolic interventions as adjunctive treatment strategies. By integrating metabolic, immunologic, and microbiome data, we synthesize emerging evidence to better understand the gut–skin–obesity interplay and guide future therapeutic innovations.

Introduction

Changes in Skin Physiology in Obese Patients

Obesity and Inflammatory Skin Disorders

Altered Skin Microbiota in Inflammatory Skin Disorders

Altered Gut Microbiota in Obesity

Altered Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Skin Disorders

Therapeutic Approaches and Future Directions

Limitations and Confounding Factors

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government, grant number: 2023R1A2C1007759, “Grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Korea, grant number: RS-2023-KH-136575 & RS-2025-02217860, Grant of Translational R&D Project through Institute for Bio-Medical convergence, Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea (H.S.K.).

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Ethical Statements

This article is a review of previously published studies and does not involve any new studies of human participants or animals conducted by the authors. Therefore, ethical approval and informed consent are not required.

| Author | Sample size | Methods | Key findings | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy individuals | ||||

| Brandwein et al. (2019) | 822 skin samples | 16S rRNA V4 sequencing | Skin microbiome beta diversity and relative abundance of Corynebacterium positively correlated with BMI. | BMI self-reported; cross-sectional design; no control for comorbidities; Specific skin area could not be identified |

| Rood et al. (2018) | 31 obese and 27 normal-weight pregnant women | 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequencing | In the mid-abdomen and Pfannenstiel area, obese individuals had higher levels of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, and lower levels of Actinobacteria compared to controls. | Small sample size; pregnant women only (reduced generalizability); potential confounders (pregnancy-related factors, surgical prep. antibiotics) not fully controlled |

| Vongsa et al. (2019) | 20 women with high BMI (≥ 30), 20 with normal BMI | 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequencing | Women with normal BMI showed Lactobacillus-dominant flora; those with high BMI had more Finegoldia and Corynebacterium, particularly in the vulvar region. No significant differences were noted in abdominal skin. | Limited to female subjects; region-specific sampling (vulvar/abdominal), potential confounders (ethnicity, diet, hygiene practices, and hormonal variation) were not fully adjusted. |

| Walker et al. (2020) | 10 obese (BMI 35–50) postmenopausal women, 10 normal-weight (BMI 18.5–26.9) women | 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequencing | Minimal differences in overall skin microbiome composition between groups (mid lower abdomen). | Very small cohort; postmenopausal women only (reduced generalizability); potential confounders (ethnicity, diet, hygiene products, sexual activity, antibiotic history and hormonal variation) not fully adjusted. |

| Ma et al. (2024) | 198 healthy Chinese women | 16S rRNA V3-V4 sequencing | Higher BMI associated with impaired skin barrier (increased TEWL, decreased pH), increased bacterial and fungal diversity. Overweight group had elevated Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, Malassezia, Candida abundance. Significant correlations observed between skin physiology and microbial composition. | Single anatomical site (face); cross-sectional design |

| HS | ||||

| Haskin et al. (2016) | 632 HS patients | Bacterial culture of purulent drainage | The odds of detecting Firmicutes were 3.1 times higher in obese HS patients than in non-obese counterparts. | Culture-based (bias against unculturable bacteria); lack of control; potential confounders (antibiotic exposure and comorbidities) are not systematically controlled. |

| Author | Study design | Sample size | Intervention | Key findings | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis: Liraglutide | |||||

| Buysschaert et al. (2014) | Prospective cohort | 7 patients with type 2 DM and psoriasis | 18 weeks of exenatide (5 μg BID) or liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) | Mean PASI decreased from 12.0 to 9.2 | Very small, uncontrolled case-series; Treatment & co-therapy heterogeneity; short follow-up |

| Ahern et al. (2013) | Prospective cohort | 7 patients with type 2 DM and psoriasis | 10 weeks of liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) | Median PASI decreased from 4.8 to 3.0; DLQI from 6.0 to 2.0 | Small open-label study without controls; low baseline disease activity; confounding by metabolic changes and co-therapies |

| Faurschou et al. (2015) | RCT | 20 psoriasis patients | 8 weeks of liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) vs. placebo | No significant difference in PASI and DLQI between groups | Small sample size and short treatment duration; no significant PASI/DLQI benefit over placebo |

| Xu et al. (2019) | Prospective cohort | 7 patients with type 2 DM and psoriasis | 12 weeks of liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) | Mean PASI dropped from 15.7 to 2.2; DLQI from 21.6 to 4.1 | Very small, uncontrolled study; short follow-up; potential confounders for metabolic and treatment regimens for diabetes |

| Lin et al. (2022) | RCT | 25 psoriasis patients with type 2 DM | 12 weeks of liraglutide vs. placebo | Significant PASI improvement in treatment vs. control group | Small, single-center, open-label trial; short follow-up; confounding by metabolic effects |

| Psoriasis: Pioglitazone | |||||

| Singh and Bhansali et al. (2016) | RCT | 60 psoriasis patients with MS | 12 weeks of pioglitazone vs. metformin vs. placebo | Significant improvement in PASI, PGA, and ESI with pioglitazone and metformin | Single center, open label study; short treatment window |

| Ghiasi et al. (2019) | RCT | 60 psoriasis patients with MS | 10 weeks of phototherapy + pioglitazone vs. phototherapy + placebo | Greater PASI reduction in pioglitazone group | Single center study; short treatment window; fixed-dose design |

| Lajevardi et al. (2015) | RCT | 44 psoriasis patients | 16 weeks of MTX + pioglitazone vs. MTX alone | PASI75 achieved in 63.6% (combo) vs. 9.1% (MTX alone) | Assessor-blinded only; single center trial with small sample size; male-predominant cohort |

| HS: Liraglutide | |||||

| Nicolau et al. (2023) | Prospective cohort | 14 HS patients with obesity | 12 weeks of liraglutide (3 mg) | Significant reductions in BMI, Hurley stage, and DLQI | Small sample size; short follow-up duration; lack of a control or placebo group |

- Abulnaja K. 2009. Changes in the hormone and lipid profile of obese adolescent Saudi females with acne vulgaris. Braz J Med Biol Res. 42: 501–505.ArticlePubMed

- Adams J, Ganio MS, Burchfield JM, Matthews AC, Werner RN, et al. 2015. Effects of obesity on body temperature in otherwise-healthy females when controlling hydration and heat production during exercise in the heat. Eur J Appl Physiol. 115: 167–176.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Ahern T, Tobin AM, Corrigan M, Hogan A, Sweeney C, et al. 2013. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue therapy for psoriasis patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 27: 1440–1443.ArticlePubMed

- Aron-Wisnewsky J, Warmbrunn MV, Nieuwdorp M, Clément K. 2021. Metabolism and metabolic disorders and the microbiome: the intestinal microbiota associated with obesity, lipid metabolism, and metabolic health-pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Gastroenterology. 160: 573–599.ArticlePubMed

- Asadi A, Shadab Mehr N, Mohamadi MH, Shokri F, Heidary M, et al. 2022. Obesity and gut-microbiota-brain axis: a narrative review. J Clin Lab Anal. 36: e24420.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Boer J. 2016. Resolution of hidradenitis suppurativa after weight loss by dietary measures, especially on frictional locations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 30: 895–896.ArticlePubMedLink

- Brandwein M, Katz I, Katz A, Kohen R. 2019. Beyond the gut: skin microbiome compositional changes are associated with BMI. Hum Microbiome J. 13: 100063.Article

- Buysschaert M, Baeck M, Preumont V, Marot L, Hendrickx E, et al. 2014. Improvement of psoriasis during glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue therapy in type 2 diabetes is associated with decreasing dermal γδ T-cell number: a prospective case-series study. Br J Dermatol. 171: 155–161.ArticlePubMed

- Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, et al. 2007. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 56: 1761–1772.ArticlePubMed

- Carrascosa J, Rocamora V, Fernandez-Torres R, Jimenez-Puya R, Moreno J, et al. 2014. Obesity and psoriasis: inflammatory nature of obesity, relationship between psoriasis and obesity, and therapeutic implications. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 105: 31–44.ArticlePubMed

- Chang G, Chen B, Zhang L. 2022. Efficacy of GLP-1rA, liraglutide, in plaque psoriasis treatment with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort and before-after studies. J Dermatol Treat. 33: 1299–1305.Article

- Chang G, Wang J, Song J, Zhang Z, Zhang L. 2020. Efficacy and safety of pioglitazone for treatment of plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Dermatol Treat. 31: 680–686.Article

- Chang HW, Yan D, Singh R, Liu J, Lu X, et al. 2018. Alteration of the cutaneous microbiome in psoriasis and potential role in Th17 polarization. Microbiome. 6: 154.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Chen YJ, Ho HJ, Tseng CH, Lai ZL, Shieh JJ, et al. 2018. Intestinal microbiota profiling and predicted metabolic dysregulation in psoriasis patients. Exp Dermatol. 27: 1336–1343.ArticlePubMedLink

- Cheng Z, Zhang L, Yang L, Chu H. 2022. The critical role of gut microbiota in obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13: 1025706.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Collard M, Grbic N, Mumber H, Wyant WA, Shen L, et al. 2025. Gut microbiome in adult and pediatric patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatology. 161: 770–773.ArticlePubMed

- Coppola S, Avagliano C, Calignano A, Berni Canani R. 2021. The protective role of butyrate against obesity and obesity-related diseases. Molecules. 26: 682.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Cronin P, McCarthy S, Hurley C, Ghosh TS, Cooney JC, et al. 2023. Comparative diet-gut microbiome analysis in Crohn’s disease and Hidradenitis suppurativa. Front Microbiol. 14: 1289374.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Danielsson G, Eklof B, Grandinetti A, L. Kistner R. 2002. The influence of obesity on chronic venous disease. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 36: 271–276.ArticlePubMedLink

- Darlenski R, Mihaylova V, Handjieva-Darlenska T. 2022. The link between obesity and the skin. Front Nutr. 9: 855573.ArticlePubMedPMC

- de Jongh RT, Serné EH, IJzerman RG, De Vries G, Stehouwer CD. 2004. Impaired microvascular function in obesity: implications for obesity-associated microangiopathy, hypertension, and insulin resistance. Circulation. 109: 2529–2535.ArticlePubMed

- De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Goncalves D, Vinera J, Zitoun C, et al. 2014. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell. 156: 84–96.ArticlePubMed

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, Dopazo H, Penas-Steinhardt A. 2020. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new Psoriasis-Microbiome Index. Sci Rep. 10: 12754.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Deplewski D, Rosenfield RL. 1999. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors have different effects on sebaceous cell growth and differentiation. Endocrinology. 140: 4089–4094.ArticlePubMed

- do Nascimento AP, Monte-Alto-Costa A. 2011. Both obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats present delayed cutaneous wound healing. Br J Nutr. 106: 603–611.ArticlePubMed

- Dokoshi T, Chen Y, Cavagnero KJ, Rahman G, Hakim D, et al. 2024. Dermal injury drives a skin to gut axis that disrupts the intestinal microbiome and intestinal immune homeostasis in mice. Nature Communications. 15: 3009.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Dong Z, Tan Z, Chen Z. 2021. Association of BMI and lipid profiles with axillary osmidrosis: a retrospective case-control study. J Dermatol Treat. 32: 654–657.Article

- Duncan SH, Lobley G, Holtrop G, Ince J, Johnstone A, et al. 2008. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes. 32: 1720–1724.ArticlePDF

- Enser M, Avery N. 1984. Mechanical and chemical properties of the skin and its collagen from lean and obese-hyperglycaemic (ob/ob) mice. Diabetologia. 27: 44–49.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Faurschou A, Gyldenløve M, Rohde U, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, et al. 2015. Lack of effect of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide on psoriasis in glucose-tolerant patients – a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 29: 555–559.ArticlePubMedLink

- Fletcher JM, Moran B, Petrasca A, Smith CM. 2020. IL-17 in inflammatory skin diseases psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Immunol. 201: 121–134.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, et al. 2013. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 504: 446–450.ArticlePubMed

- Ghiasi M, Ebrahimi S, Lajevardi V, Taraz M, Azizpour A. 2019. Efficacy and safety of pioglitazone plus phototherapy versus phototherapy in patients with plaque type psoriasis: a Double Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. J Dermatol Treat. 30: 664–667.Article

- González-López MA, Vilanova I, Ocejo-Viñals G, Arlegui R, Navarro I, et al. 2020. Circulating levels of adiponectin, leptin, resistin and visfatin in non-diabetics patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol Res. 312: 595–600.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Guet-Revillet H, Jais JP, Ungeheuer MN, Coignard-Biehler H, Duchatelet S, et al. 2017. The microbiological landscape of anaerobic infections in hidradenitis suppurativa: a prospective metagenomic study. Clin Infect Dis. 65: 282–291.ArticlePubMed

- Haskin A, Fischer AH, Okoye GA. 2016. Prevalence of firmicutes in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa in obese patients. JAMA dermatol. 152: 1276–1278.ArticlePubMed

- Hirt PA, Castillo DE, Yosipovitch G, Keri JE. 2019. Skin changes in the obese patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 81: 1037–1057.ArticlePubMed

- Huang L, Gao R, Yu N, Zhu Y, Ding Y, et al. 2019. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota was closely associated with psoriasis. Sci China Life Sci. 62: 807–815.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Izquierdo AG, Crujeiras AB, Casanueva FF, Carreira MC. 2019. Leptin, obesity, and leptin resistance: where are we 25 years later? Nutrients. 11: 2704.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Jung YR, Lee JH, Sohn KC, Lee Y, Seo YJ, et al. 2017. Adiponectin signaling regulates lipid production in human sebocytes. PLoS One. 12: e0169824.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kam S, Collard M, Lam J, Alani RM. 2021. Gut microbiome perturbations in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a case series. J Invest Dermatol. 141: 225–228.ArticlePubMed

- Kataru RP, Park HJ, Baik JE, Li C, Shin J, et al. 2020. Regulation of lymphatic function in obesity. Front Physiol. 11: 459.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kern PA, Di Gregorio GB, Lu T, Rassouli N, Ranganathan G. 2003. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor-α expression. Diabetes. 52: 1779–1785.ArticlePubMed

- Koh A, Molinaro A, Ståhlman M, Khan MT, Schmidt C, et al. 2018. Microbially produced imidazole propionate impairs insulin signaling through mTORC1. Cell. 175: 947–961.ArticlePubMed

- Koliada A, Syzenko G, Moseiko V, Budovska L, Puchkov K, et al. 2017. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol. 17: 120.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Krajewski PK, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC. 2023. Adipokines as an important link between hidradenitis suppurativa and obesity: a narrative review. Br J Dermatol. 188: 320–327.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Kromann C, IBlER KS, Kristiansen V, Jemec GB. 2014. The influence of body weight on the prevalence and severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 94: 553–557.ArticlePubMed

- Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Sotiriadis D, Goulis DG. 2018. Serum leptin, resistin, and adiponectin concentrations in psoriasis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Dermatology. 233: 378–389.ArticleLink

- Lajevardi V, Hallaji Z, Daklan S, Abedini R, Goodarzi A, et al. 2015. The efficacy of methotrexate plus pioglitazone vs. methotrexate alone in the management of patients with plaque‐type psoriasis: a single‐blinded randomized controlled trial. Int J Dermatol. 54: 95–101.ArticlePubMedLink

- Larouche J, Sheoran S, Maruyama K, Martino MM. 2018. Immune regulation of skin wound healing: mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Adv Wound Care. 7: 209–231.Article

- Lelonek E, Krajewski PK, Szepietowski JC. 2025. Gut microbiome correlations in hidradenitis suppurativa patients. J Clin Med. 14: 5074.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. 2006. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 444: 1022–1023.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Li N, Han X, Ruan M, Huang F, Yang L, et al. 2024. Prebiotic inulin controls Th17 cells mediated central nervous system autoimmunity through modulating the gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids. Gut Microbes. 16: 2402547.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lin L, Xu X, Yu Y, Ye H, He X, et al. 2022. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide therapy for psoriasis patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized-controlled trial. J Dermatol Treat. 33: 1428–1434.Article

- Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano JM Jr, Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. 2013. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci Transl Med. 5: 178ra41.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Liu C, Liu X, Li X. 2024. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and hidradenitis suppurativa: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Microbiol. 15: 1302822.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lv Y, Bian H, Jing Y, Zhou J. 2025. IL-17A inhibitors modulate skin microbiome in psoriasis: implications for microbial homeostasis. J Transl Med. 23: 817.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Ma L, Zhang H, Jia Q, Bai T, Yang S, et al. 2024. Facial physiological characteristics and skin microbiomes changes are associated with body mass index (BMI). Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 513–528.ArticleLink

- Malara A, Hughes R, Jennings L, Sweeney C, Lynch M, et al. 2018. Adipokines are dysregulated in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 178: 792–793.ArticlePubMedLink

- Matsumoto M, Ibuki A, Minematsu T, Sugama J, Horii M, et al. 2014. Structural changes in dermal collagen and oxidative stress levels in the skin of J apanese overweight males. Int J Cosmet Sci. 36: 477–484.ArticlePubMed

- McCarthy S, Barrett M, Kirthi S, Pellanda P, Vlckova K, et al. 2022. Altered skin and gut microbiome in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 142: 459–468.e15.ArticlePubMed

- Mintoff D, Agius R, Benhadou F, Das A, Frew JW, et al. 2023. Obesity and hidradenitis suppurativa: targeting meta-inflammation for therapeutic gain. Clin Exp Dermatol. 48: 984–990.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Mishra SP, Wang B, Jain S, Ding J, Rejeski J, et al. 2023. A mechanism by which gut microbiota elevates permeability and inflammation in obese/diabetic mice and human gut. Gut. 72: 1848–1865.ArticlePubMed

- Naik HB, Jo JH, Paul M, Kong HH. 2020. Skin microbiota perturbations are distinct and disease severity-dependent in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 140: 922.ArticlePubMed

- Natividad JM, Agus A, Planchais J, Lamas B, Jarry AC, et al. 2018. Impaired aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand production by the gut microbiota is a key factor in metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 28: 737–749.e4.ArticlePubMed

- Navarro-López V, Martínez-Andrés A, Ramírez-Boscá A, Ruzafa-Costas B, Núñez-Delegido E, et al. 2019. Efficacy and safety of oral administration of a mixture of probiotic strains in patients with psoriasis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 99: 1078–1084.ArticlePubMed

- Nicolau J, Nadal A, Sanchís P, Pujol A, Masmiquel L, et al. 2023. Liraglutide for the treatment of obesity among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Med Clin. 162: 118–122.Article

- Öğüt ND, Hasçelik G, Atakan N. 2022. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a case-control study and review of the literature. Derma Pract Concept. 12: e2022191.Article

- Pathak P, Xie C, Nichols RG, Ferrell JM, Boehme S, et al. 2018. Intestine farnesoid X receptor agonist and the gut microbiota activate G-protein bile acid receptor-1 signaling to improve metabolism. Hepatology. 68: 1574–1588.ArticlePubMedLink

- Pedersen HK, Gudmundsdottir V, Nielsen HB, Hyotylainen T, Nielsen T, et al. 2016. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature. 535: 376–381.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Pierpont YN, Dinh TP, Salas RE, Johnson EL, Wright TG, et al. 2014. Obesity and surgical wound healing: a current review. ISRN Obes. 2014: 638936.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, et al. 2013. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 341: 1241214.ArticlePubMed

- Ring H, Sigsgaard V, Thorsen J, Fuursted K, Fabricius S, et al. 2019. The microbiome of tunnels in hidradenitis suppurativa patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 33: 1775–1780.ArticlePubMedLink

- Ring HC, Thorsen J, Saunte DM, Lilje B, Bay L, et al. 2017. The follicular skin microbiome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa and healthy controls. JAMA dermatol. 153: 897–905.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Rood KM, Buhimschi IA, Jurcisek JA, Summerfield TL, Zhao G, et al. 2018. Skin microbiota in obese women at risk for surgical site infection after cesarean delivery. Sci Rep. 8: 8756.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Schneider AM, Cook LC, Zhan X, Banerjee K, Cong Z, et al. 2020. Loss of skin microbial diversity and alteration of bacterial metabolic function in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 140: 716–720.ArticlePubMed

- Seth D, Ehlert AN, Golden JB, Damiani G, McCormick TS, et al. 2020. Interaction of resistin and systolic blood pressure in psoriasis severity. J Invest Dermatol. 140: 1279.ArticlePubMed

- Shapiro J, Cohen NA, Shalev V, Uzan A, Koren O, et al. 2019. Psoriatic patients have a distinct structural and functional fecal microbiota compared with controls. J Dermatol. 46: 595–603.ArticlePubMedLink

- Shi B, Bangayan NJ, Curd E, Taylor PA, Gallo RL, et al. 2016. The skin microbiome is different in pediatric versus adult atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 138: 1233–1236.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Singh S, Bhansali A. 2016. Randomized placebo control study of insulin sensitizers (Metformin and Pioglitazone) in psoriasis patients with metabolic syndrome (Topical Treatment Cohort). BMC Dermatol. 16: 12.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Sivanand A, Gulliver WP, Josan CK, Alhusayen R, Fleming PJ. 2020. Weight loss and dietary interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 24: 64–72.ArticlePubMedLink

- Sugerman HJ. 2001. Effects of increased intra-abdominal pressure in severe obesity. Surg Clin North Am. 81: 1063–1075.ArticlePubMed

- Sze MA, Schloss PD. 2016. Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome. mBio. 7: e01018-16.ArticlePubMedPMCLink

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, et al. 2006. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 444: 1027–1031.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Upala S, Sanguankeo A. 2015. Effect of lifestyle weight loss intervention on disease severity in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 39: 1197–1202.ArticlePDF

- van Straalen KR, Prens EP, Gudjonsson JE. 2022. Insights into hidradenitis suppurativa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 149: 1150–1161.ArticlePubMed

- Vongsa R, Hoffman D, Shepard K, Koenig D. 2019. Comparative study of vulva and abdominal skin microbiota of healthy females with high and average BMI. BMC Microbiol. 19: 16.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Walker JM, Garcet S, Aleman JO, Mason CE, Danko D, et al. 2020. Obesity and ethnicity alter gene expression in skin. Sci Rep. 10: 14079.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Wang L, Xiao W, Zheng Y, Xiao R, Zhu G, et al. 2012. High dose lipopolysaccharide triggers polarization of mouse thymic Th17 cells in vitro in the presence of mature dendritic cells. Cell Immunol. 274: 98–108.ArticlePubMed

- Wen C, Pan Y, Gao M, Wang J, Huang K, et al. 2023. Altered gut microbiome composition in nontreated plaque psoriasis patients. Microb Pathog. 175: 105970.ArticlePubMed

- Xiao S, Zhang G, Jiang C, Liu X, Wang X, et al. 2021. Deciphering gut microbiota dysbiosis and corresponding genetic and metabolic dysregulation in psoriasis patients using metagenomics sequencing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 11: 605825.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Xu X, Lin L, Chen P, Yu Y, Chen S, et al. 2019. Treatment with liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, improves effectively the skin lesions of psoriasis patients with type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 150: 167–173.ArticlePubMed

- Yew YW, Mina T, Ng HK, Lam BCC, Riboli E, et al. 2023. Investigating causal relationships between obesity and skin barrier function in a multi-ethnic Asian general population cohort. Int J Obes. 47: 963–969.ArticlePDF

- Yoshida H, Ishii M, Akagawa M. 2019. Propionate suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis via GPR43/AMPK signaling pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 672: 108057.ArticlePubMed

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. 2007. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 56: 901–916.ArticlePubMed

- Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, De Luca A, Giovannini G, et al. 2013. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity. 39: 372–385.ArticlePubMed

- Zhao L, Zhang F, Ding X, Wu G, Lam YY, et al. 2018. Gut bacteria selectively promoted by dietary fibers alleviate type 2 diabetes. Science. 359: 1151–1156.ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

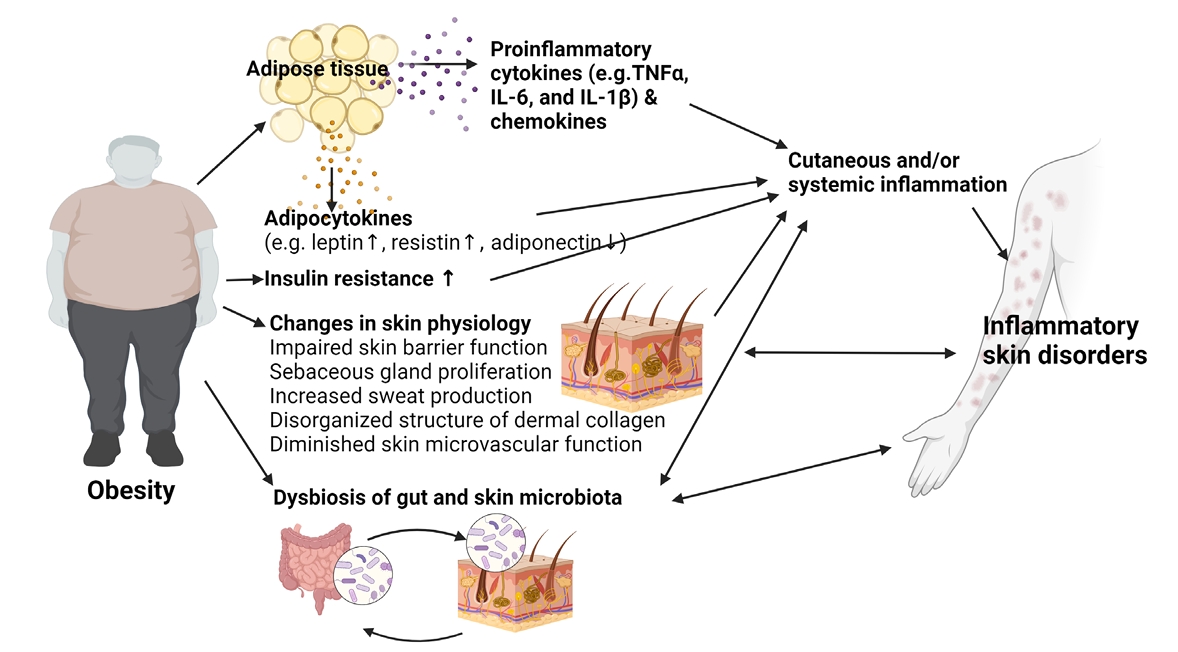

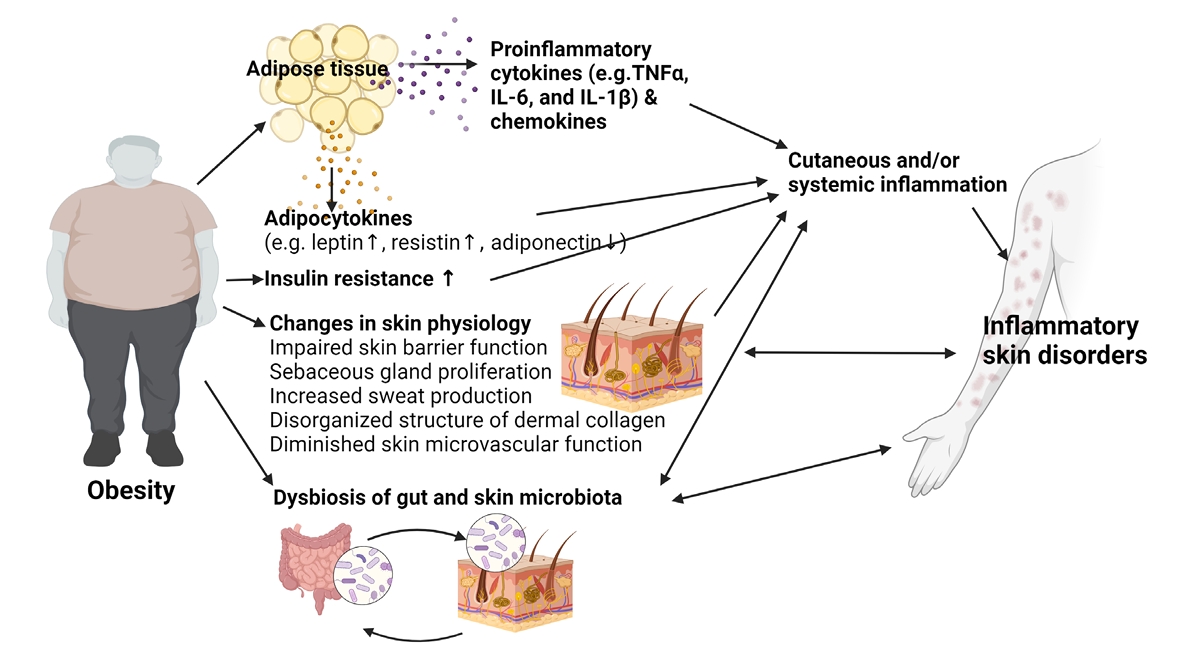

Fig. 1.

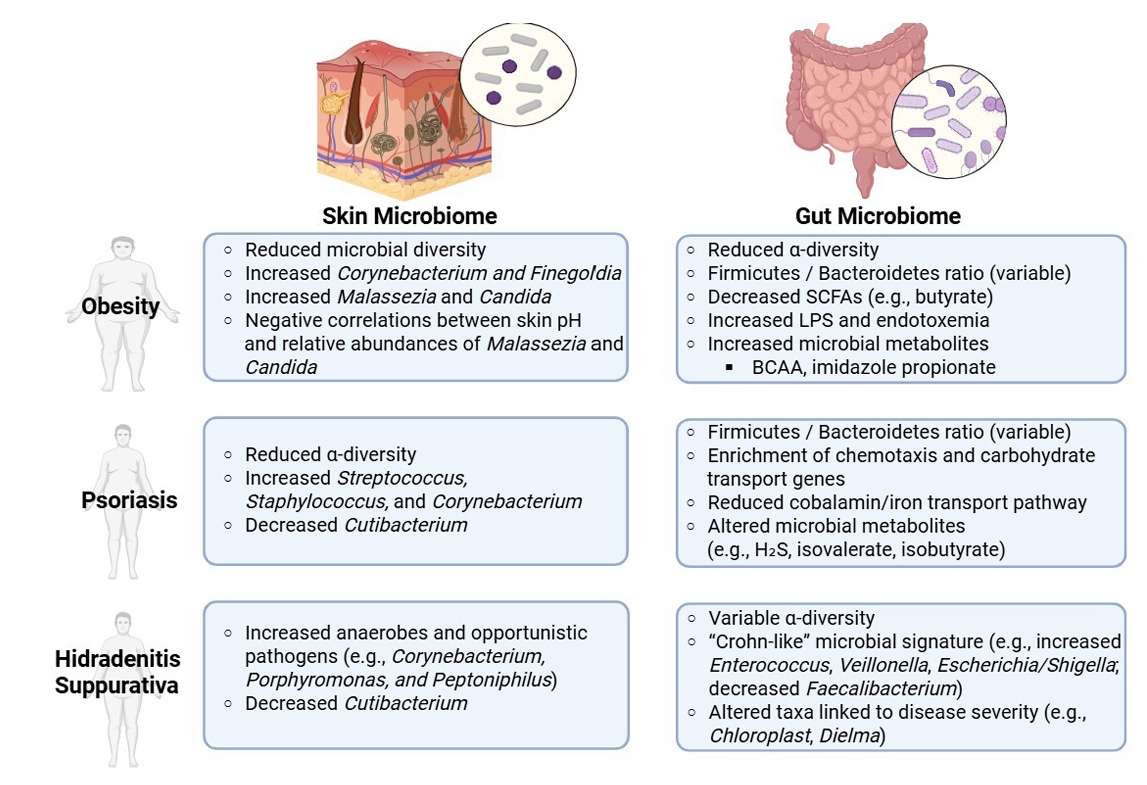

Fig. 2.

| Author | Sample size | Methods | Key findings | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy individuals | ||||

| |

822 skin samples | 16S rRNA V4 sequencing | Skin microbiome beta diversity and relative abundance of Corynebacterium positively correlated with BMI. | BMI self-reported; cross-sectional design; no control for comorbidities; Specific skin area could not be identified |

| |

31 obese and 27 normal-weight pregnant women | 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequencing | In the mid-abdomen and Pfannenstiel area, obese individuals had higher levels of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, and lower levels of Actinobacteria compared to controls. | Small sample size; pregnant women only (reduced generalizability); potential confounders (pregnancy-related factors, surgical prep. antibiotics) not fully controlled |

| |

20 women with high BMI (≥ 30), 20 with normal BMI | 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequencing | Women with normal BMI showed Lactobacillus-dominant flora; those with high BMI had more Finegoldia and Corynebacterium, particularly in the vulvar region. No significant differences were noted in abdominal skin. | Limited to female subjects; region-specific sampling (vulvar/abdominal), potential confounders (ethnicity, diet, hygiene practices, and hormonal variation) were not fully adjusted. |

| |

10 obese (BMI 35–50) postmenopausal women, 10 normal-weight (BMI 18.5–26.9) women | 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequencing | Minimal differences in overall skin microbiome composition between groups (mid lower abdomen). | Very small cohort; postmenopausal women only (reduced generalizability); potential confounders (ethnicity, diet, hygiene products, sexual activity, antibiotic history and hormonal variation) not fully adjusted. |

| |

198 healthy Chinese women | 16S rRNA V3-V4 sequencing | Higher BMI associated with impaired skin barrier (increased TEWL, decreased pH), increased bacterial and fungal diversity. Overweight group had elevated Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, Malassezia, Candida abundance. Significant correlations observed between skin physiology and microbial composition. | Single anatomical site (face); cross-sectional design |

| HS | ||||

| |

632 HS patients | Bacterial culture of purulent drainage | The odds of detecting Firmicutes were 3.1 times higher in obese HS patients than in non-obese counterparts. | Culture-based (bias against unculturable bacteria); lack of control; potential confounders (antibiotic exposure and comorbidities) are not systematically controlled. |

| Author | Study design | Sample size | Intervention | Key findings | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis: Liraglutide | |||||

| |

Prospective cohort | 7 patients with type 2 DM and psoriasis | 18 weeks of exenatide (5 μg BID) or liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) | Mean PASI decreased from 12.0 to 9.2 | Very small, uncontrolled case-series; Treatment & co-therapy heterogeneity; short follow-up |

| |

Prospective cohort | 7 patients with type 2 DM and psoriasis | 10 weeks of liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) | Median PASI decreased from 4.8 to 3.0; DLQI from 6.0 to 2.0 | Small open-label study without controls; low baseline disease activity; confounding by metabolic changes and co-therapies |

| RCT | 20 psoriasis patients | 8 weeks of liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) vs. placebo | No significant difference in PASI and DLQI between groups | Small sample size and short treatment duration; no significant PASI/DLQI benefit over placebo | |

| |

Prospective cohort | 7 patients with type 2 DM and psoriasis | 12 weeks of liraglutide (1.2 mg daily) | Mean PASI dropped from 15.7 to 2.2; DLQI from 21.6 to 4.1 | Very small, uncontrolled study; short follow-up; potential confounders for metabolic and treatment regimens for diabetes |

| |

RCT | 25 psoriasis patients with type 2 DM | 12 weeks of liraglutide vs. placebo | Significant PASI improvement in treatment vs. control group | Small, single-center, open-label trial; short follow-up; confounding by metabolic effects |

| Psoriasis: Pioglitazone | |||||

| |

RCT | 60 psoriasis patients with MS | 12 weeks of pioglitazone vs. metformin vs. placebo | Significant improvement in PASI, PGA, and ESI with pioglitazone and metformin | Single center, open label study; short treatment window |

| |

RCT | 60 psoriasis patients with MS | 10 weeks of phototherapy + pioglitazone vs. phototherapy + placebo | Greater PASI reduction in pioglitazone group | Single center study; short treatment window; fixed-dose design |

| |

RCT | 44 psoriasis patients | 16 weeks of MTX + pioglitazone vs. MTX alone | PASI75 achieved in 63.6% (combo) vs. 9.1% (MTX alone) | Assessor-blinded only; single center trial with small sample size; male-predominant cohort |

| HS: Liraglutide | |||||

| |

Prospective cohort | 14 HS patients with obesity | 12 weeks of liraglutide (3 mg) | Significant reductions in BMI, Hurley stage, and DLQI | Small sample size; short follow-up duration; lack of a control or placebo group |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; RNA, Ribonucleic acid.

Abbreviation: DLQI, dermatology life quality index; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESI, erythema, scaling, and induration; MS, metabolic syndrome; MTX, methotrexate; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; PGA, physician global assessment; RCT, randomized placebo-controlled trial.

Table 1.

Table 2.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article