Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J. Microbiol > Volume 64(1); 2026 > Article

-

Full article

Development of tri-cistronic CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells incorporating PD-1/CD28 switch and cyclophilin A for enhanced solid tumor immunotherapy - Heon Ju Lee1,*, Seo Jin Hwang1, Eun Hee Jeong1, Mi Hee Chang1, Bu Yeon Heo1,2, Jaeyul Kwon2, Yoona Noh3, Jihoon Nah3,4

-

Journal of Microbiology 2026;64(1):e2510017.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2510017

Published online: January 31, 2026

1CARBio Therapeutics Co., Ltd., Cheongju 28160, Republic of Korea

2Translational Immunology Institute, Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 35015, Republic of Korea

3Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Republic of Korea

4Department of Biochemistry, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Republic of Korea

- *Correspondence. Heon Ju Lee leehj2014@naver.com

© The Microbiological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,085 Views

- 33 Download

ABSTRACT

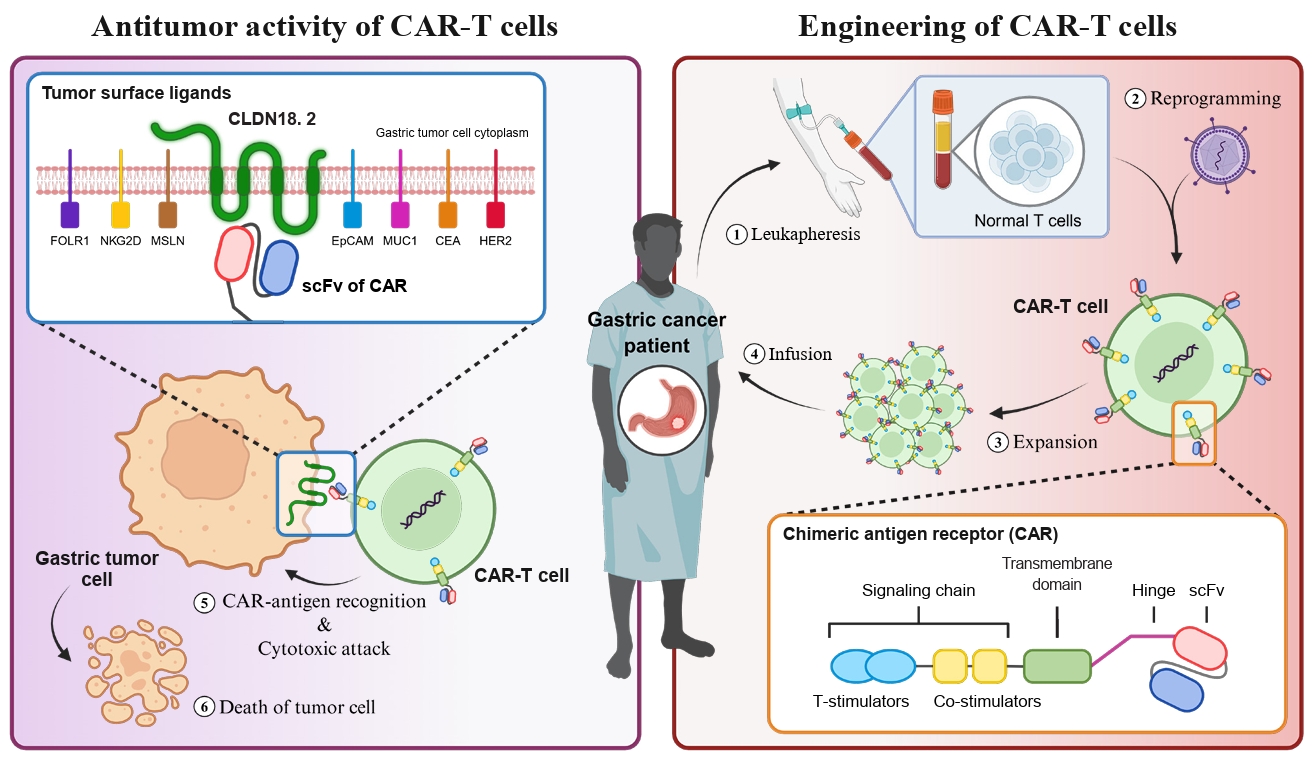

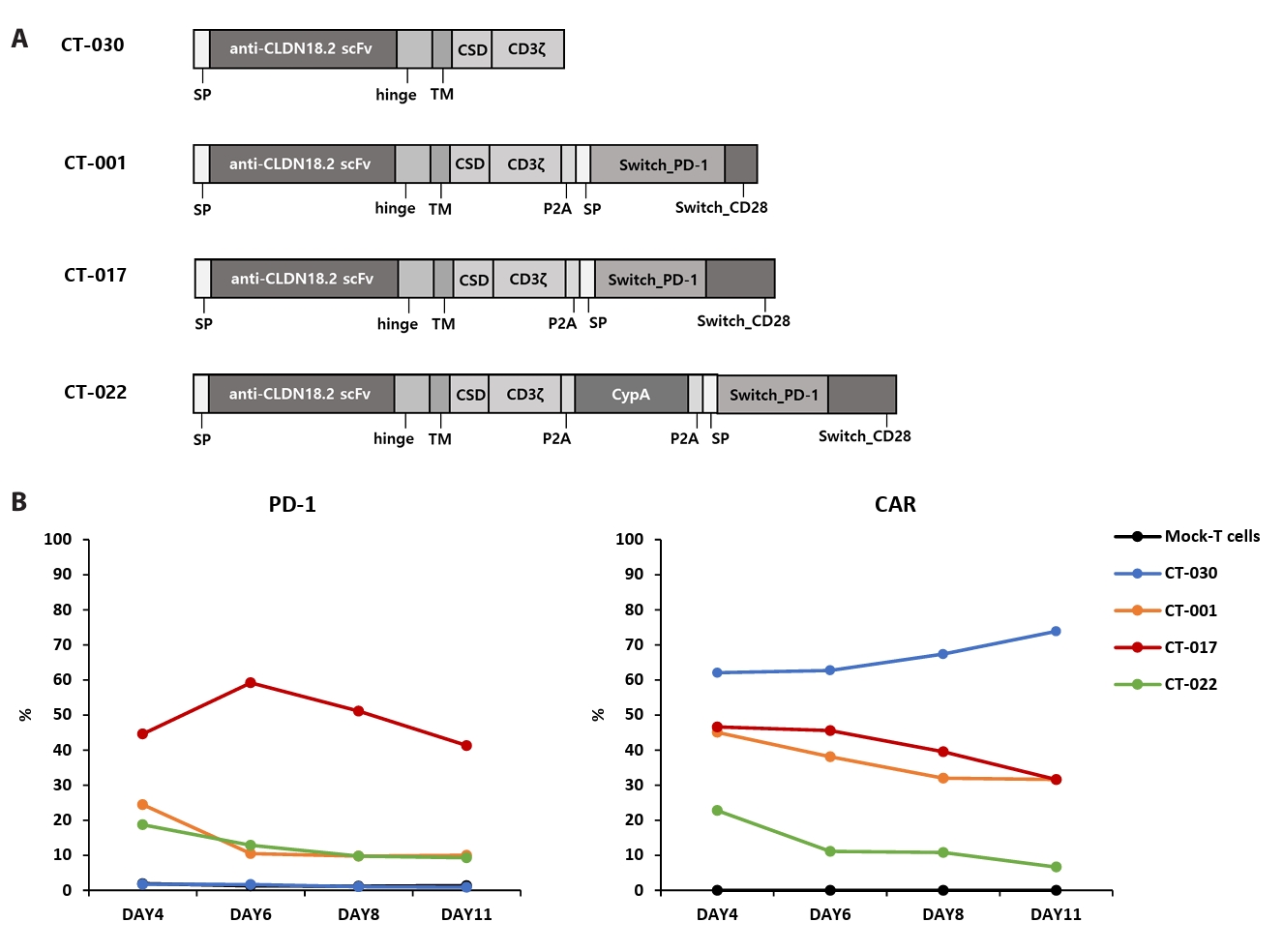

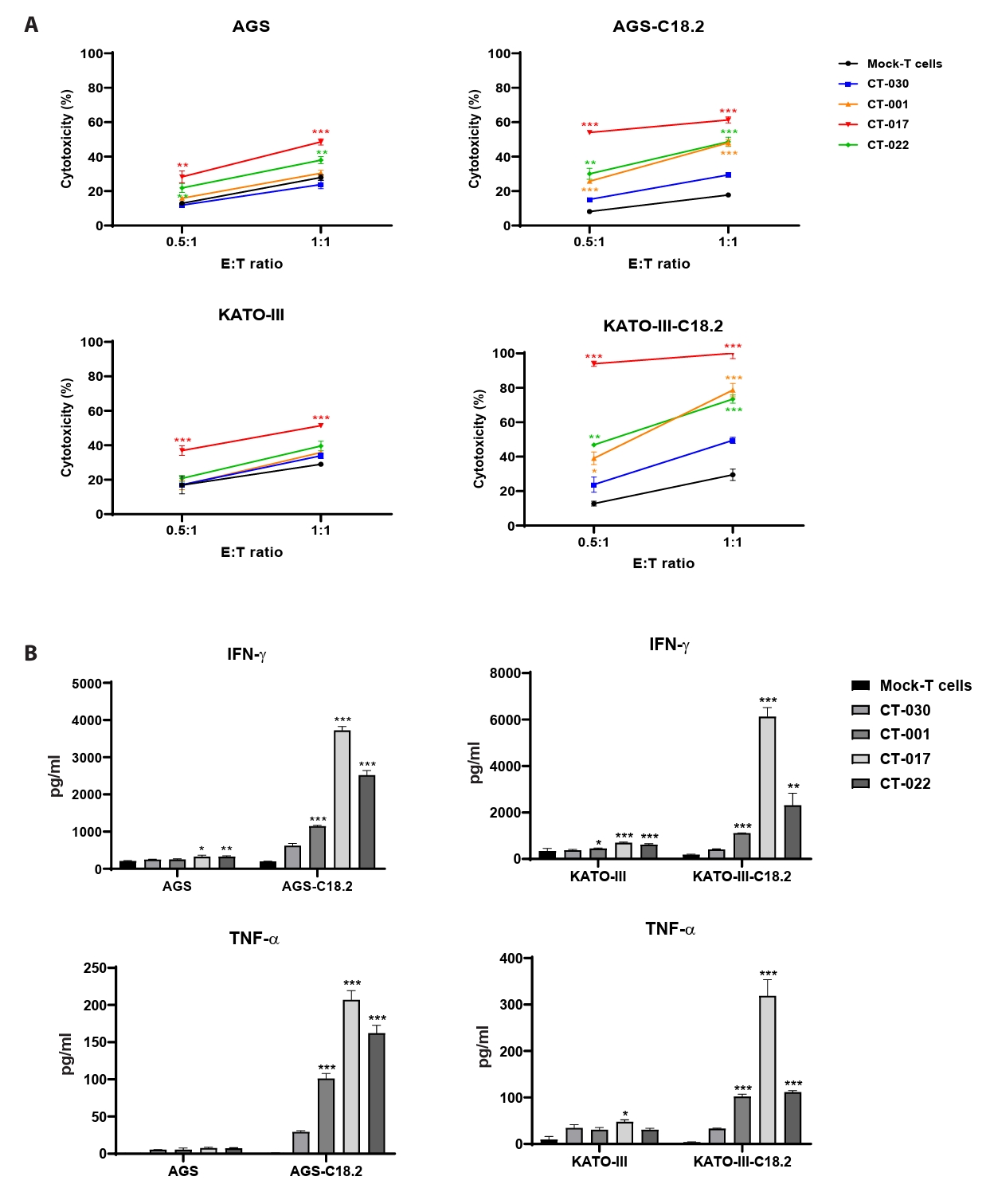

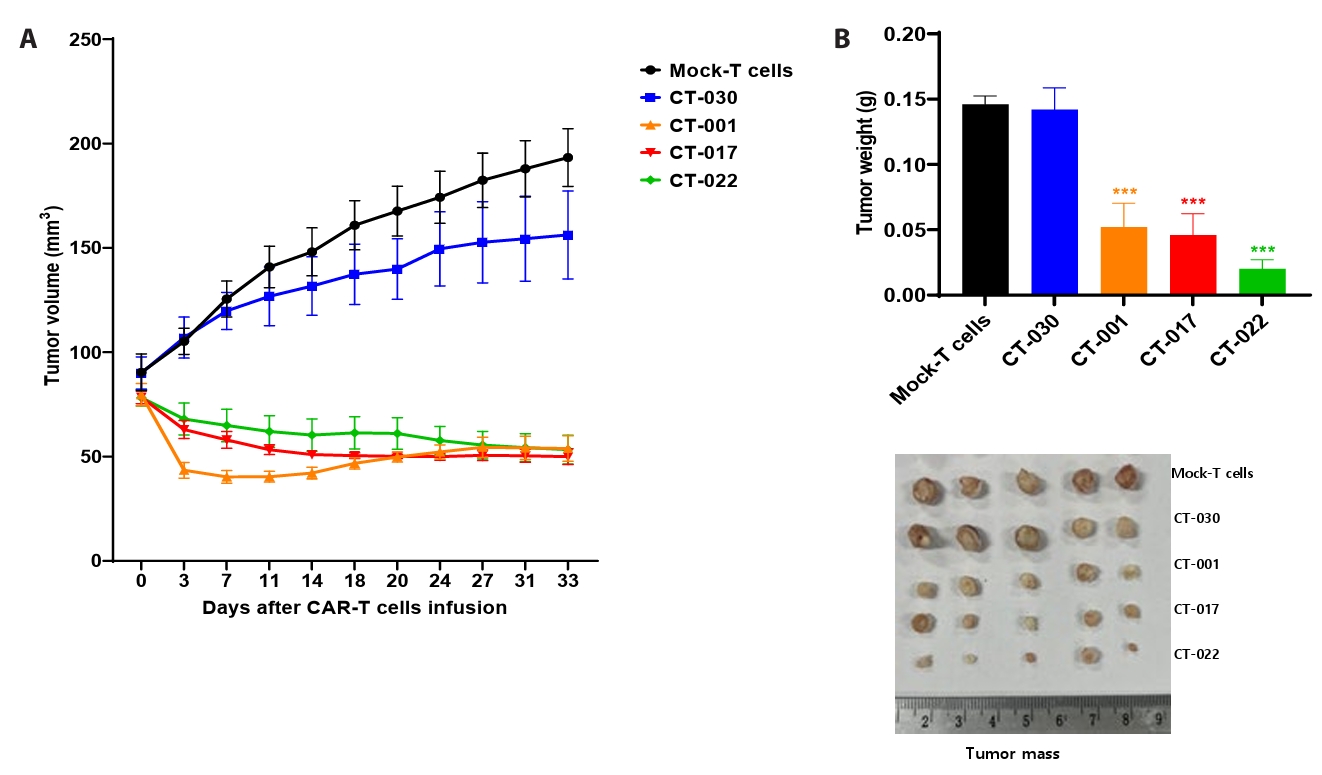

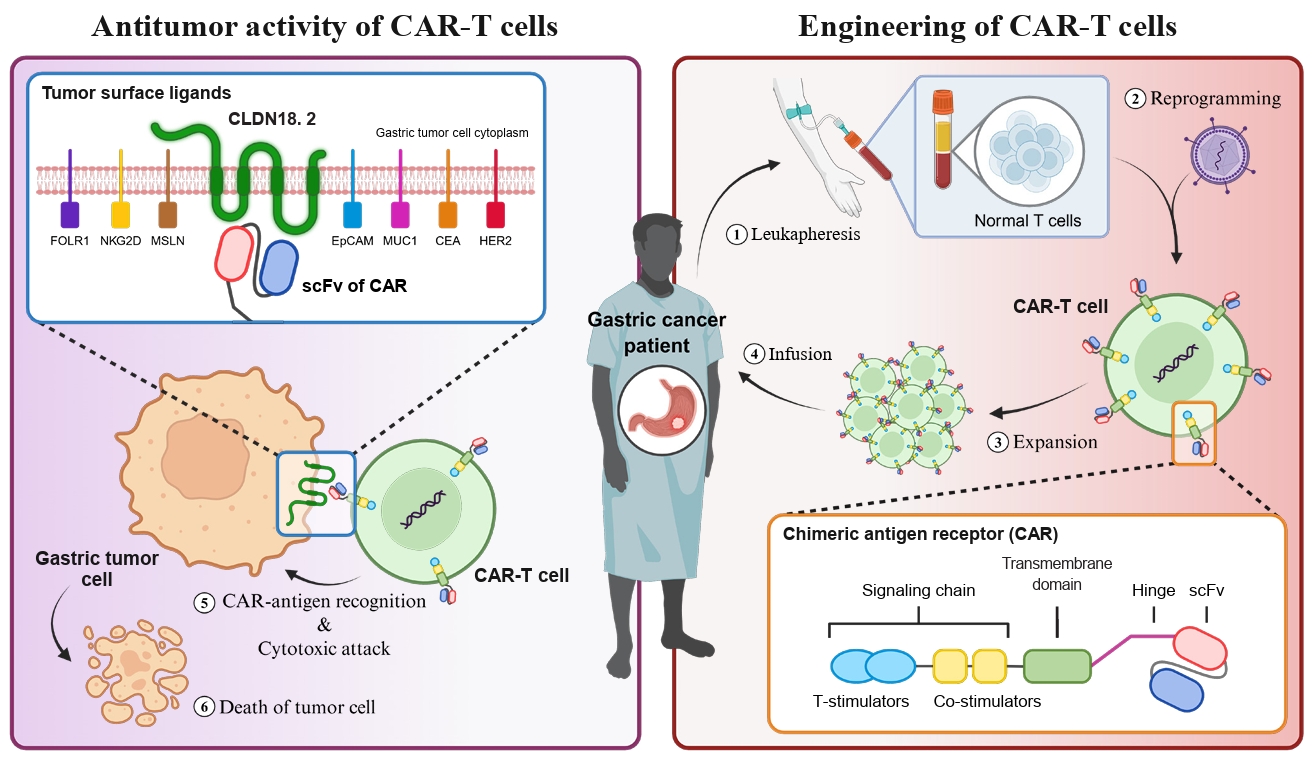

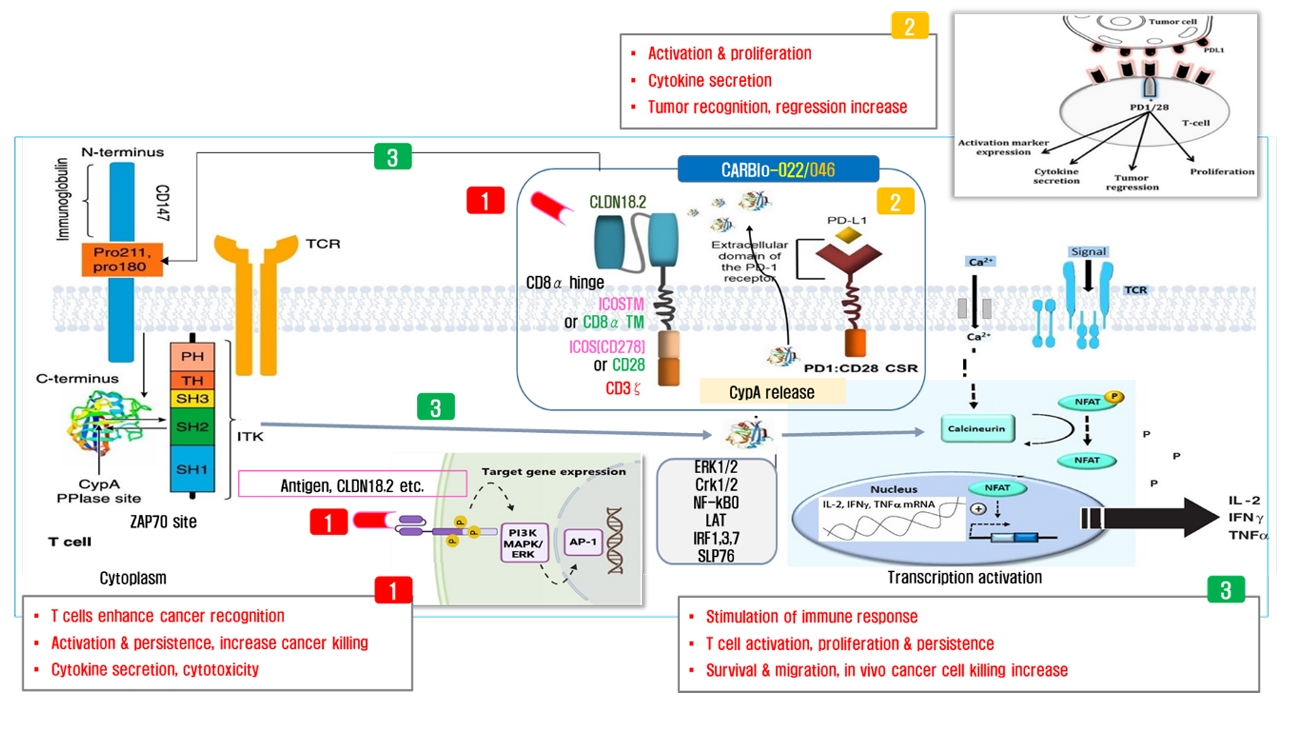

- Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy holds significant potential for the treatment of solid tumors. However, immune suppression and tumor-specific barriers limit its application. Claudin 18.2 (CLDN18.2), a gastric lineage-specific tight junction protein highly expressed in gastric and pancreatic cancers, is a promising therapeutic target. In this study, we aimed to develop a next-generation tri-cistronic CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cell platform that integrates a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/CD28 chimeric switch receptor with cyclophilin A (CypA). This platform sought to counteract PD-1–mediated immunosuppression and enhance T-cell activation and persistence. We generated CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells incorporating costimulatory inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS) domains using lentiviral vector-based recombinant engineering. We further evaluated their cytokine release, cytotoxic activity, and safety profiles. In vitro, tri-cistronic CAR-T cells exhibited markedly increased interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor α secretion and enhanced cytotoxicity against CLDN18.2-positive gastric cancer cells compared with conventional CAR-T constructs. In vivo, these cells showed superior antitumor efficacy and sustained tumor regression without observable toxicity in xenograft gastric cancer models. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the integration of PD-1/CD28 signaling and CypA within a tri-cistronic framework significantly reinforces CAR-T cell functionality and durability. This suggests strong clinical potential as a next-generation immunotherapy for solid tumors.

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Starting growth Technological R&D Program (TIPS Program, No. RS-2024-00508867) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS, Korea) in 2024. This research was partially supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the (Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the (Chungcheongbuk-do), Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-11-014-03).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statements

Animal experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Testing & Research Institute (approval no. 1st: IAC2024-1504, 2nd: IAC2024-3092).

Supplementary Information

Fig. S1.

Fig. S2.

- Anto NP, Arya AK, Muraleedharan A, Shaik J, Nath PR, et al. 2022. Cyclophilin A associates with and regulates the activity of ZAP70 in TCR/CD3-stimulated T cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 80: 7.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Baker DJ, June CH. 2024. Off-the-shelf CAR-T cells could prove paradigm shifting for autoimmune diseases. Cell. 187: 4826–4828. ArticlePubMed

- Blaeschke F, Stenger D, Apfelbeck A, Cadilha BL, Benmebarek MR, et al. 2021. Augmenting anti-CD19 and anti-CD22 CAR T-cell function using PD-1-CD28 checkpoint fusion proteins. Blood Cancer J. 11: 108.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, et al. 2001. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 27: 68–73. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Dawar FU, Xiong Y, Khattak MNK, Li J, Lin L, et al. 2017. Potential role of cyclophilin A in regulating cytokine secretion. J Leukoc Biol. 102: 989–992. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Ghartey-Kwansah G, Li Z, Feng R, Wang L, Zhou X, et al. 2018. Comparative analysis of FKBP family protein: evaluation, structure, and function in mammals and Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Dev Biol. 18: 7.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Guo F, Cui J. 2020. CAR-T in solid tumors: blazing a new trail through the brambles. Life Sci. 260: 118300.ArticlePubMed

- Jaspers JE, Khan JF, Godfrey WD, Lopez AV, Ciampricotti M, et al. 2023. IL-18-secreting CAR T cells targeting DLL3 are highly effective in small cell lung cancer models. J Clin Invest. 133: e166028. ArticlePubMedPMC

- June CH, Sadelain M. 2018. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 379: 64–73. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Kalinina A, Golubeva I, Kudryavtsev I, Khromova N, Antoshina E, et al. 2021. Cyclophilin A is a factor of antitumor defense in the early stages of tumor development. Int Immunopharmacol. 94: 107470.ArticlePubMed

- Lee HJ, Hwang SJ, Jeong EH, Chang MH. 2024. Genetically engineered CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells expressing synthetic PD1/CD28 fusion receptors produced using a lentiviral vector. J Microbiol. 62: 555–568. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Li T, Wang J. 2020. Therapeutic effect of dual CAR-T targeting PDL1 and MUC16 antigens on ovarian cancer cells in mice. BMC Cancer. 20: 678.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Lynn RC, Weber EW, Sotillo E, Gennert D, Xu P, et al. 2019. c-Jun overexpression in CAR T cells induces exhaustion resistance. Nature. 576: 293–300. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Maus MV, June CH. 2016. Making better chimeric antigen receptors for adoptive T-cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 22: 1875–1884. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Mazinani M, Rahbarizadeh F. 2022. CAR-T cell potency: from structural elements to vector backbone components. Biomark Res. 10: 70.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Mestermann K, Giavridis T, Weber J, Rydzek J, Frenz S, et al. 2019. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib acts as a pharmacologic on/off switch for CAR-T cells. Sci Transl Med. 11: eaau5907. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Miao L, Zhang Z, Ren Z, Tang F, Li Y. 2021. Obstacles and coping strategies of CAR-T cell immunotherapy in solid tumors. Front Immunol. 12: 687822.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Patel S, Brassil K, Jungsuwadee P. 2020. Expanding the role of CAR-T cell therapy to systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur Med J Hematol. 8: 105–112. Article

- Ramsdell F. 2003. Foxp3 and natural regulatory T cells: key to a cell lineage? Immunity. 19: 165–168. ArticlePubMed

- Sakaguchi S, Setoguchi R, Yagi H, Nomura T. 2006. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. In Radbruch A, Lipsky PE. (eds.), Current concepts in autoimmunity and chronic inflammation. Current topics in microbiology and immunology, vol. 305, pp. 51–66. Springer. Article

- Tahir A. 2018. Is chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy the future of autoimmunity management? Cureus. 10: e3407. ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

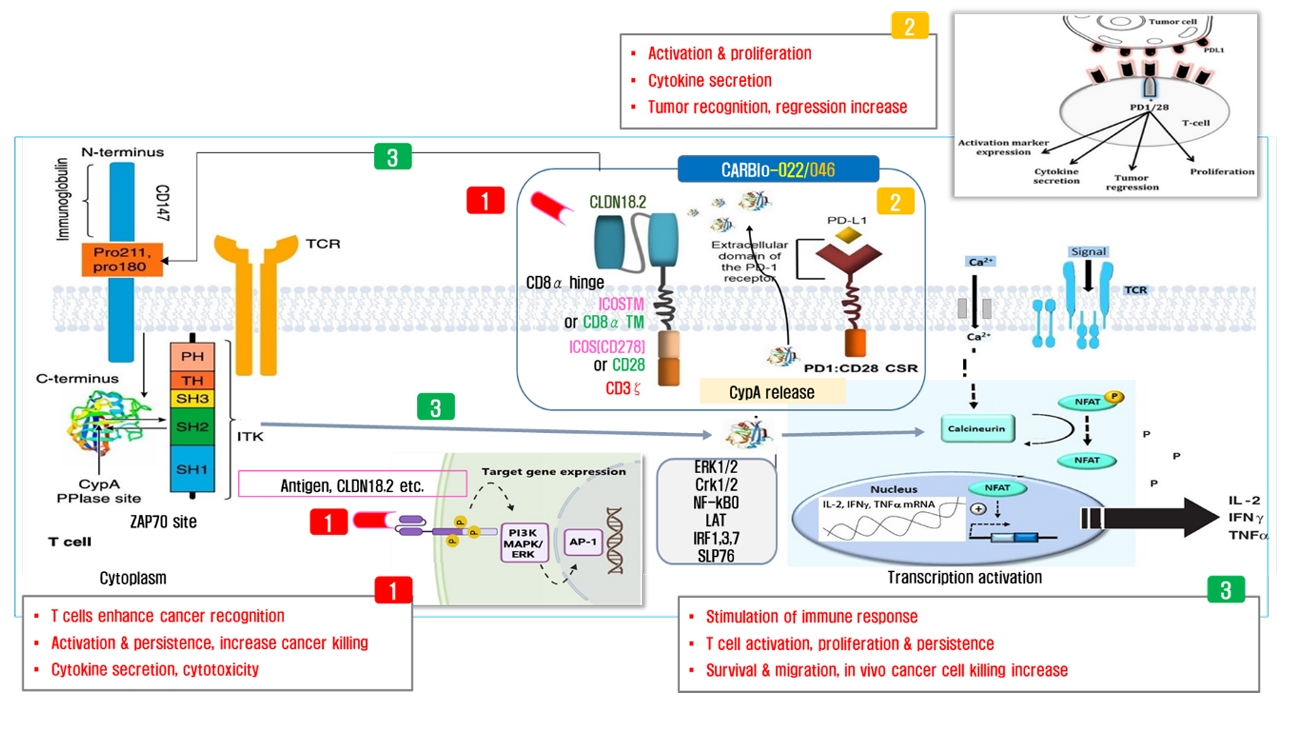

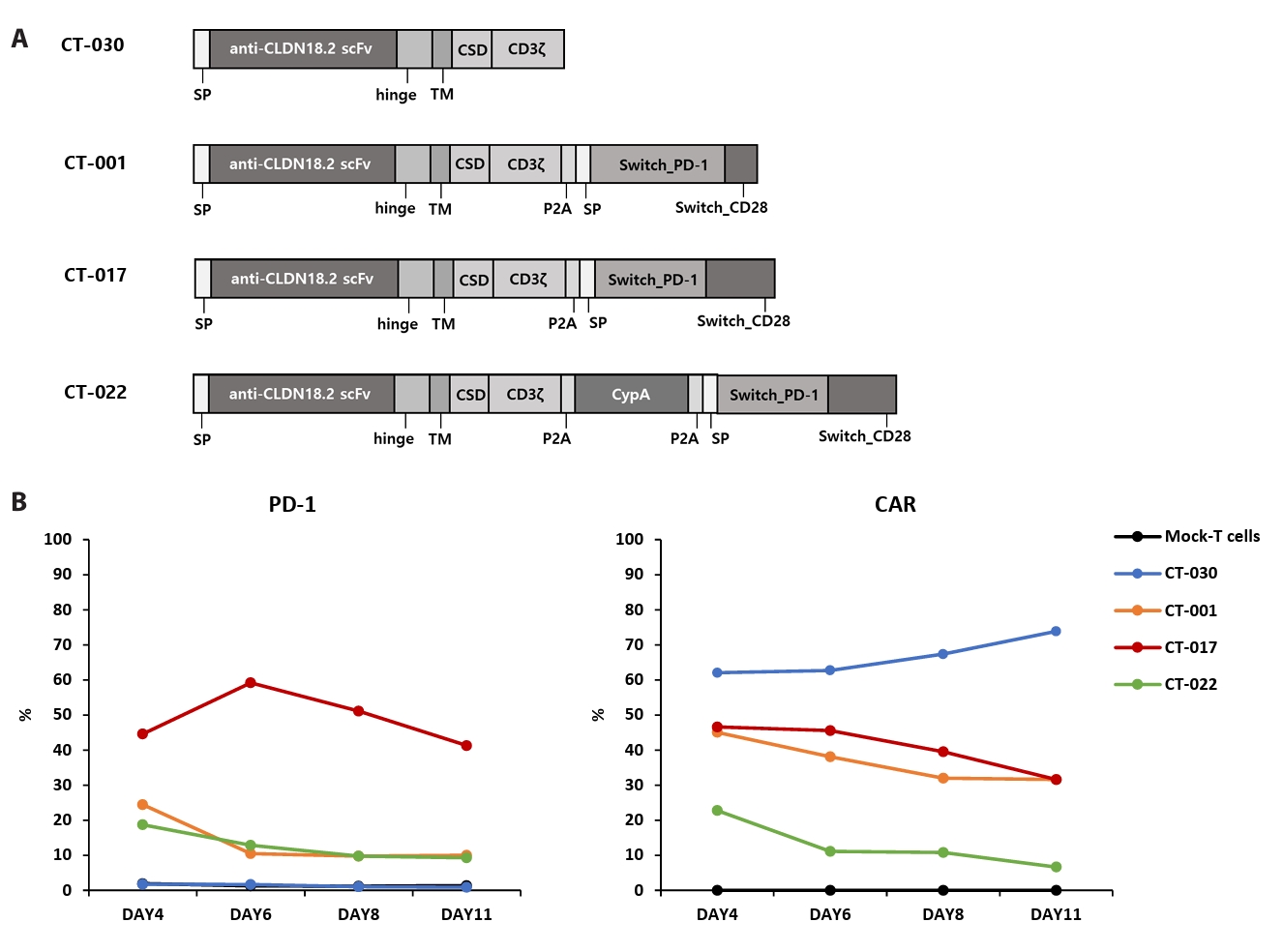

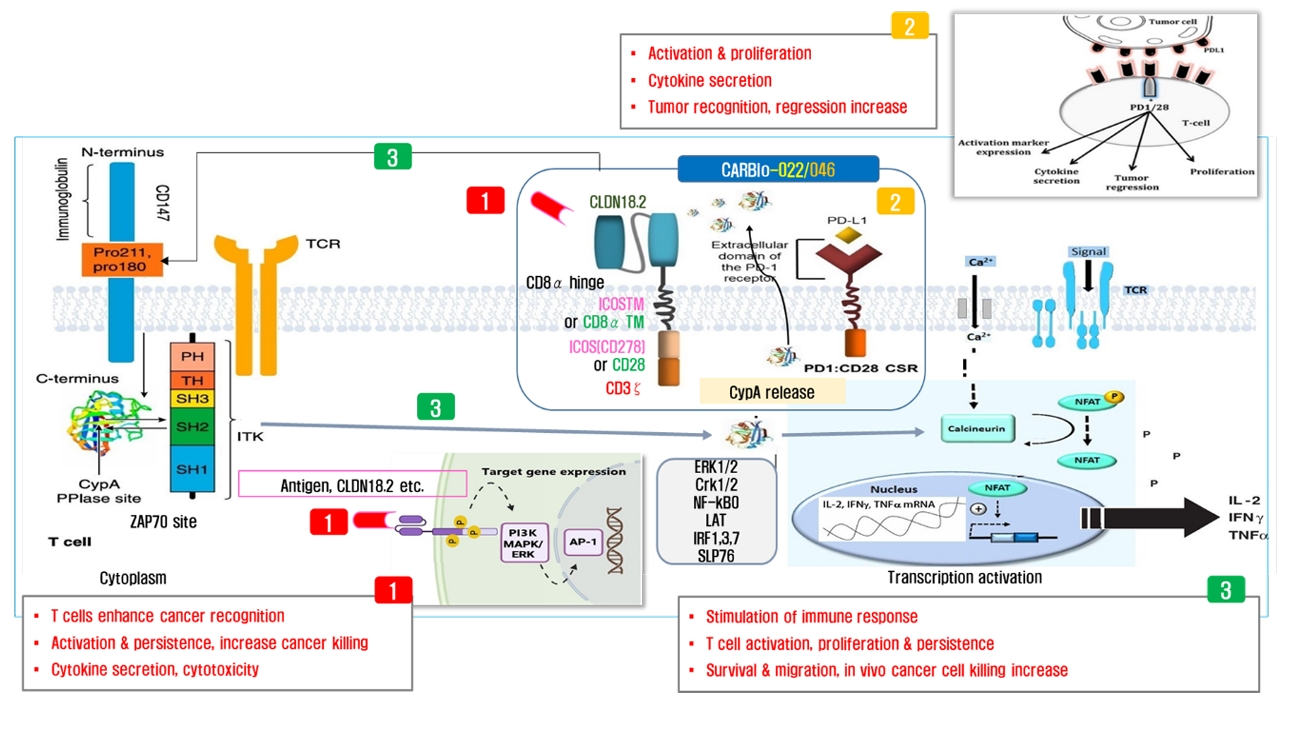

Fig. 1.

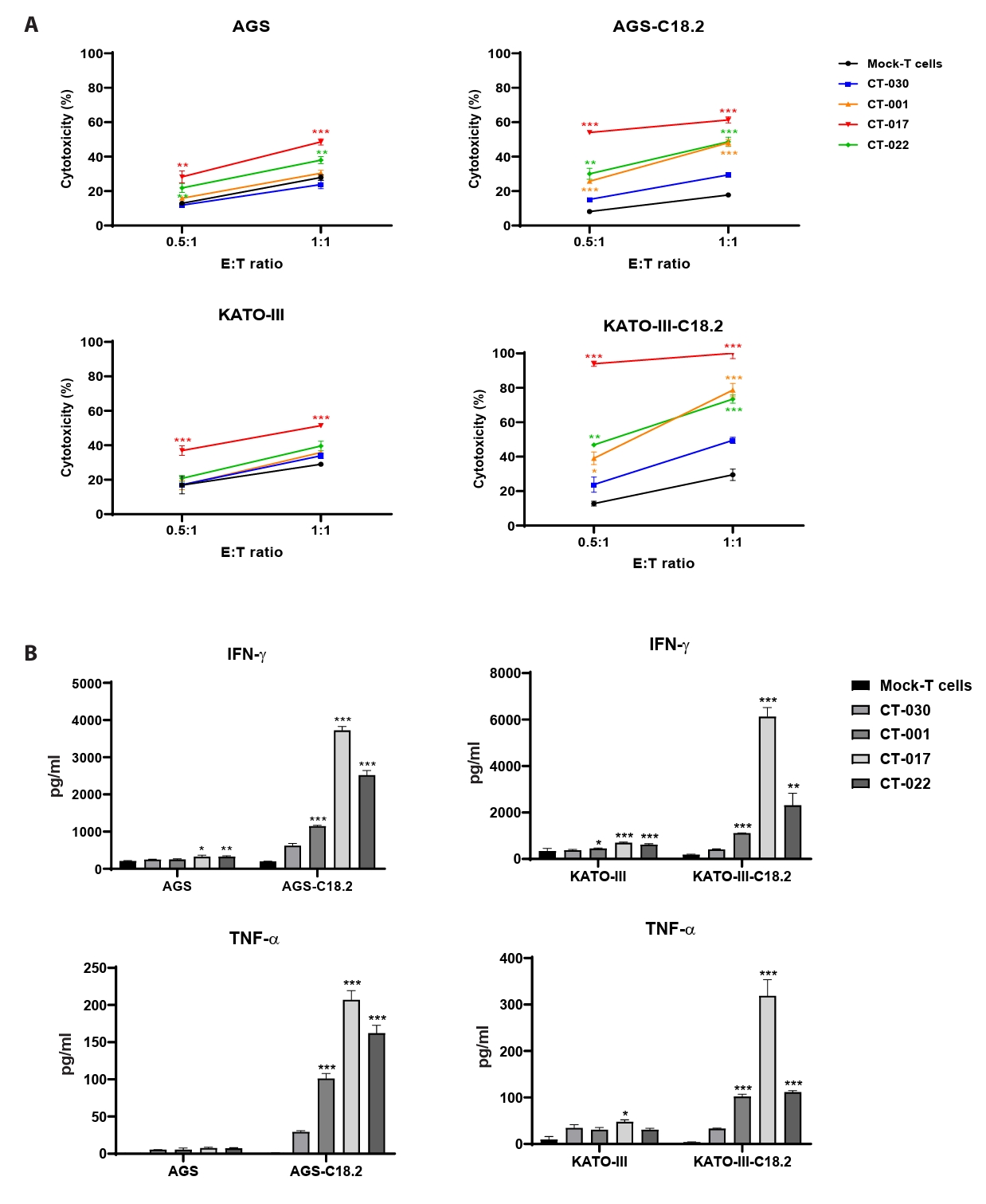

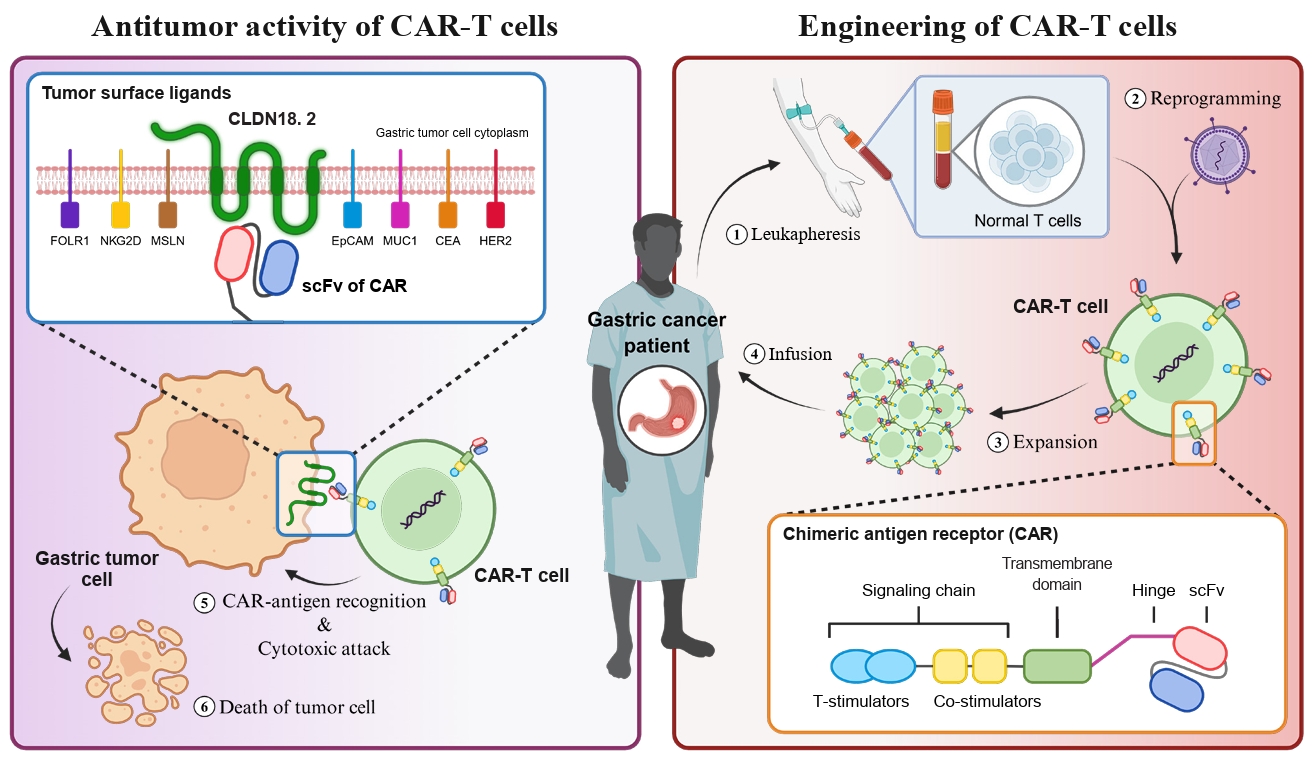

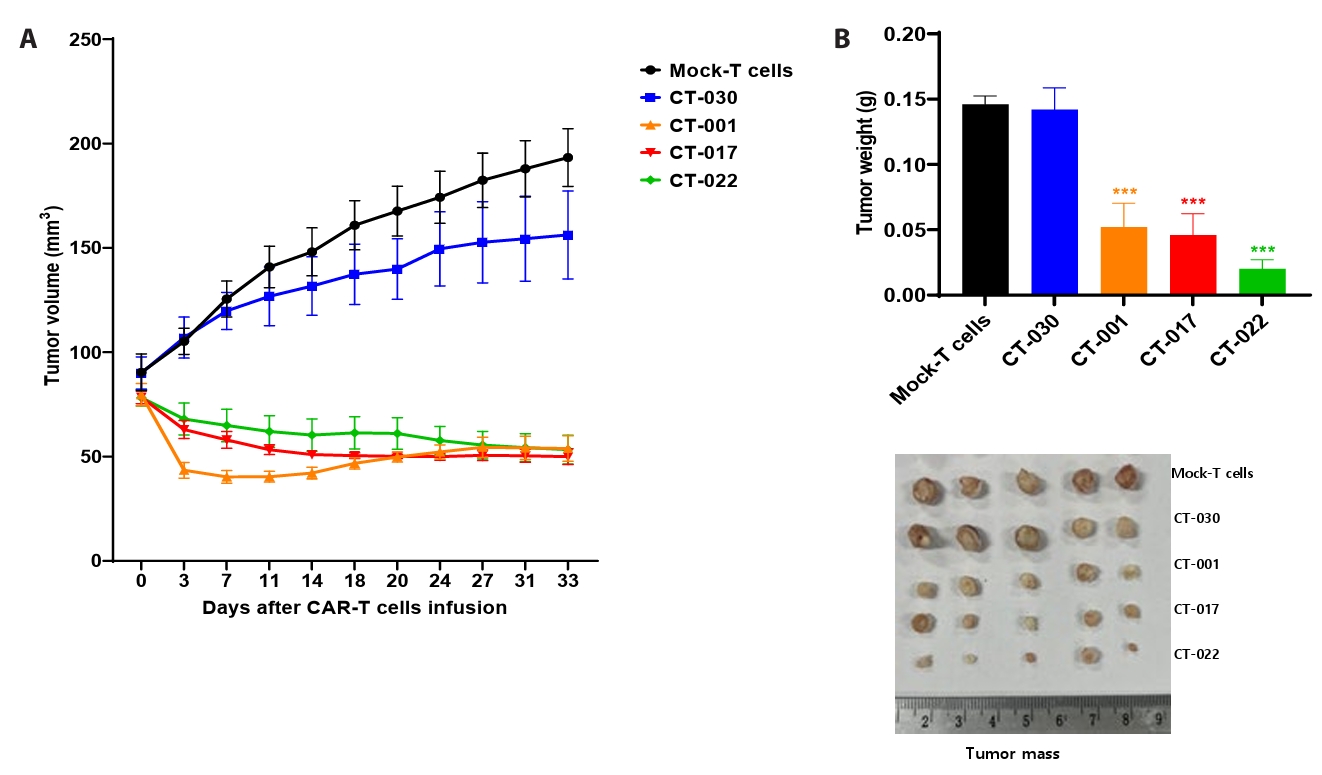

Fig. 2.

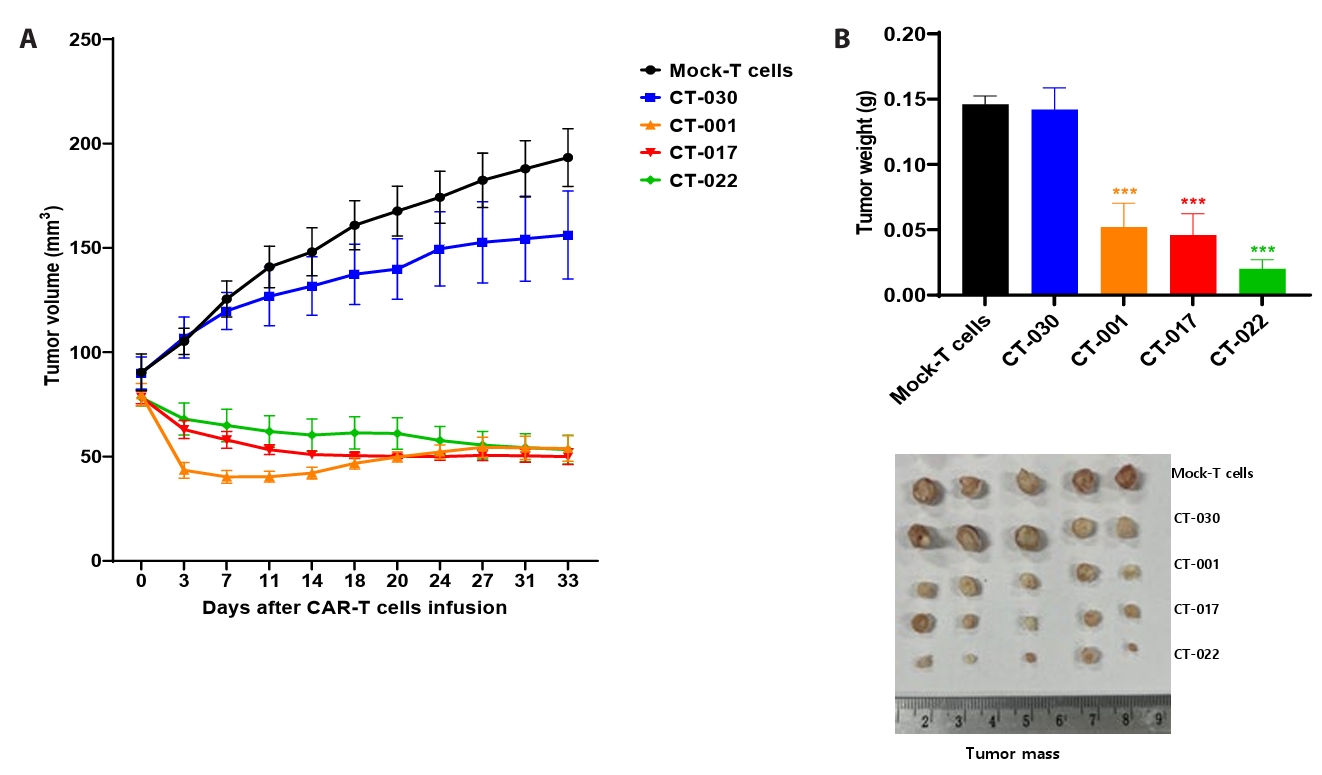

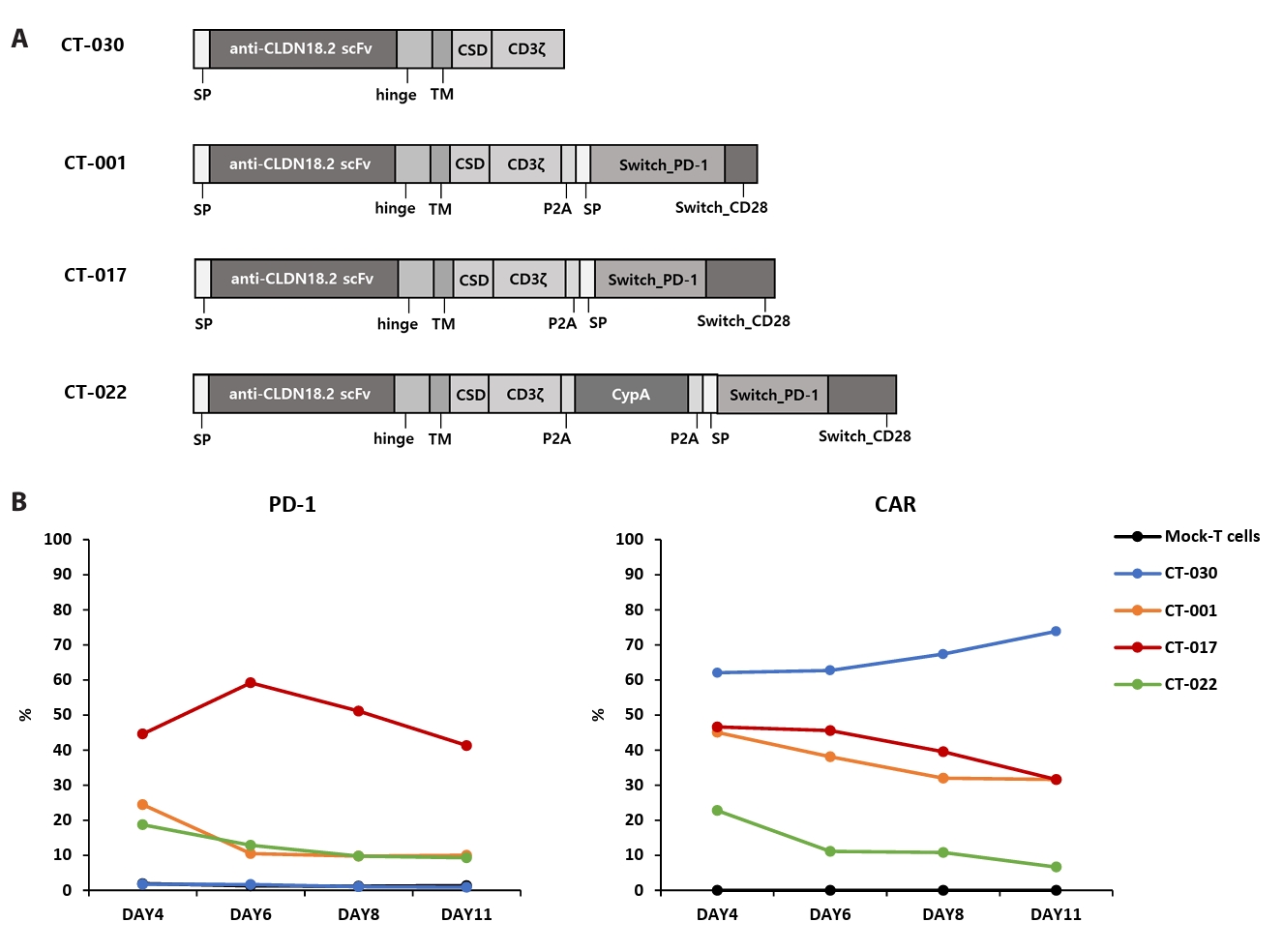

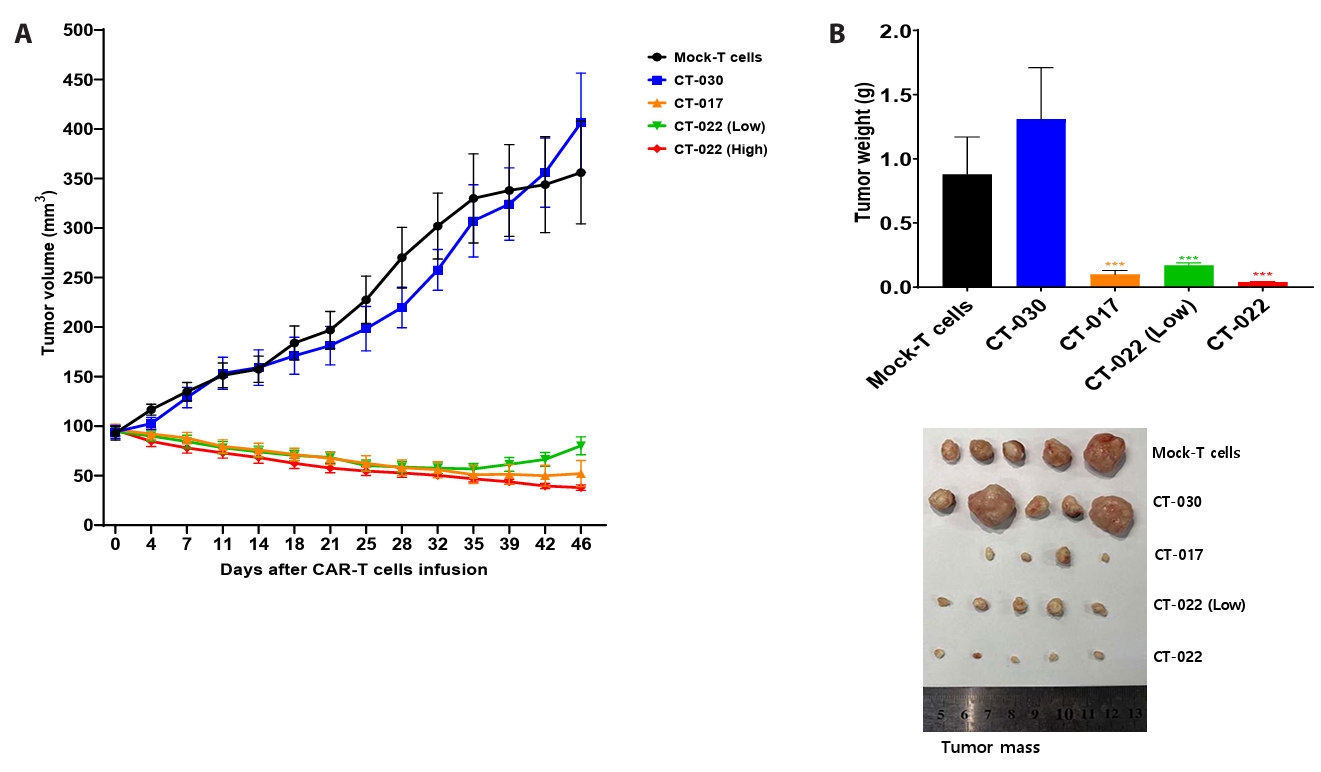

Fig. 3.

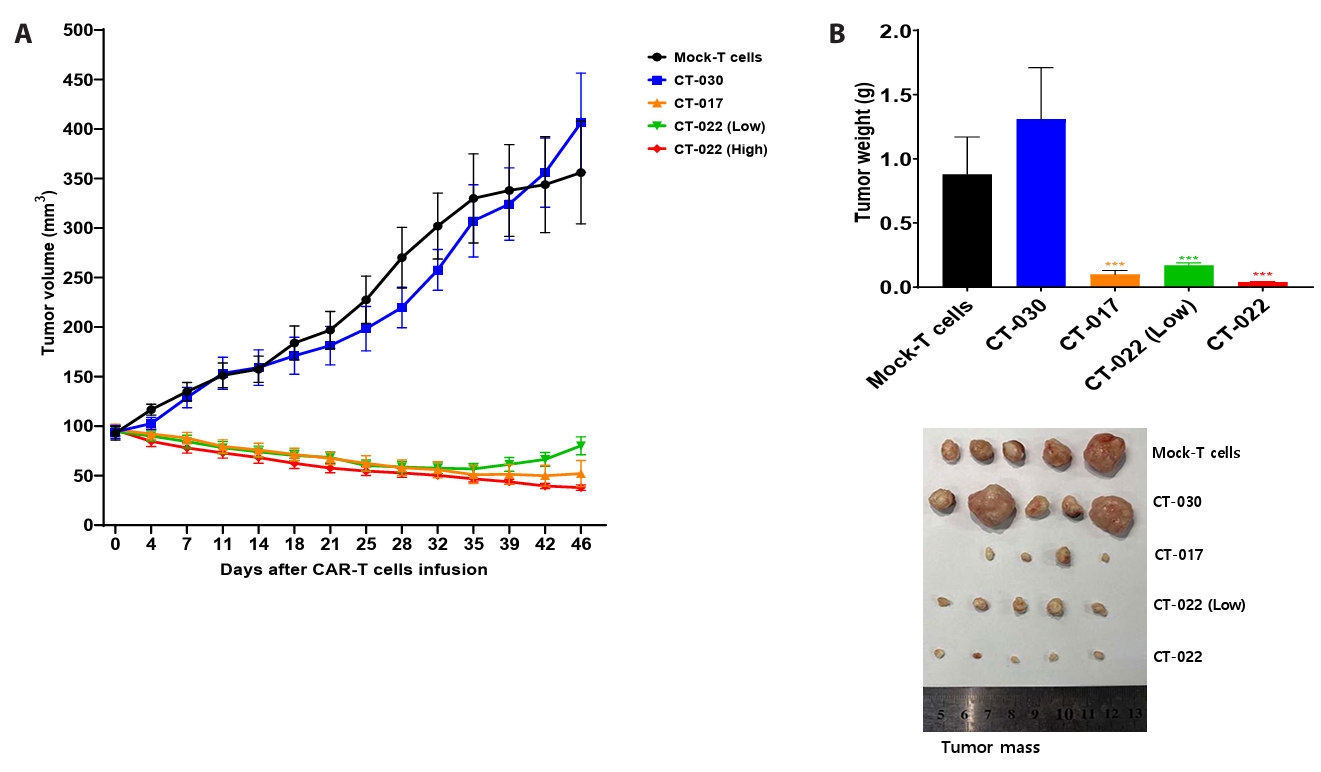

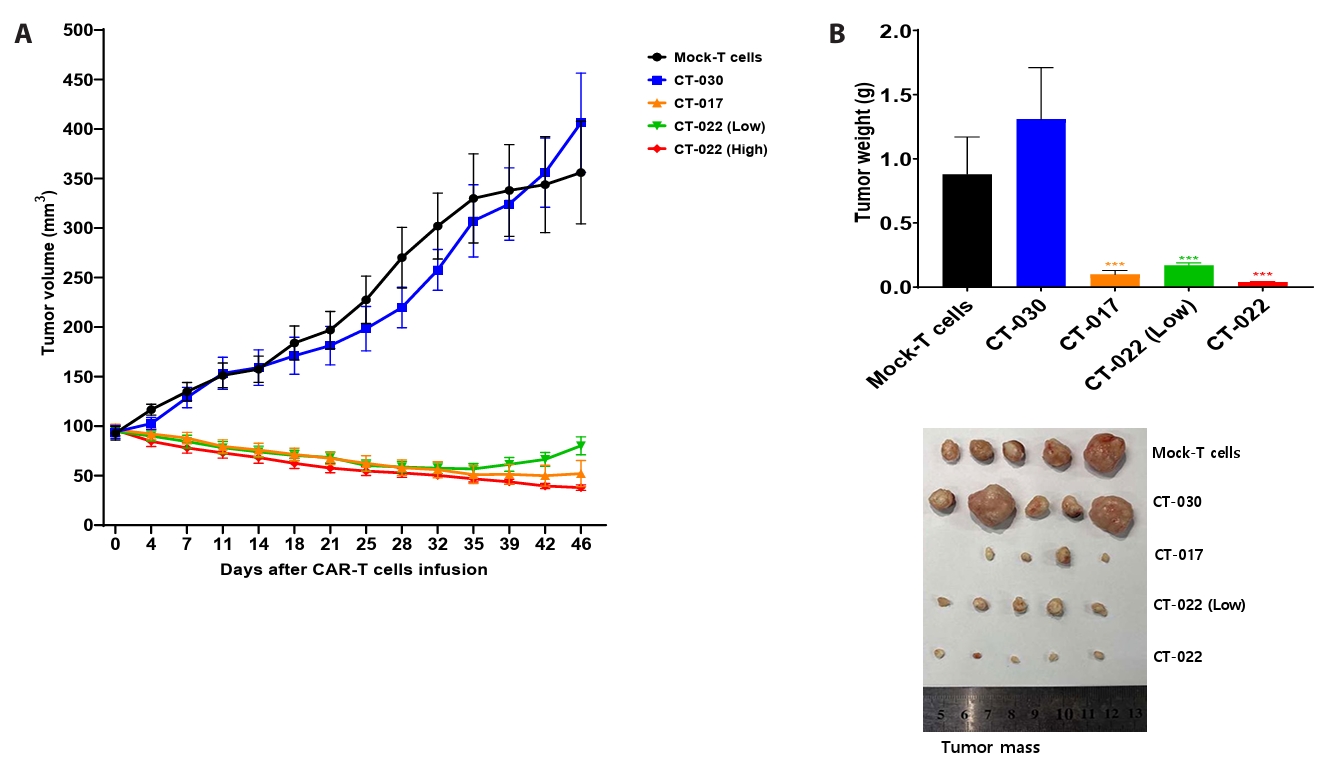

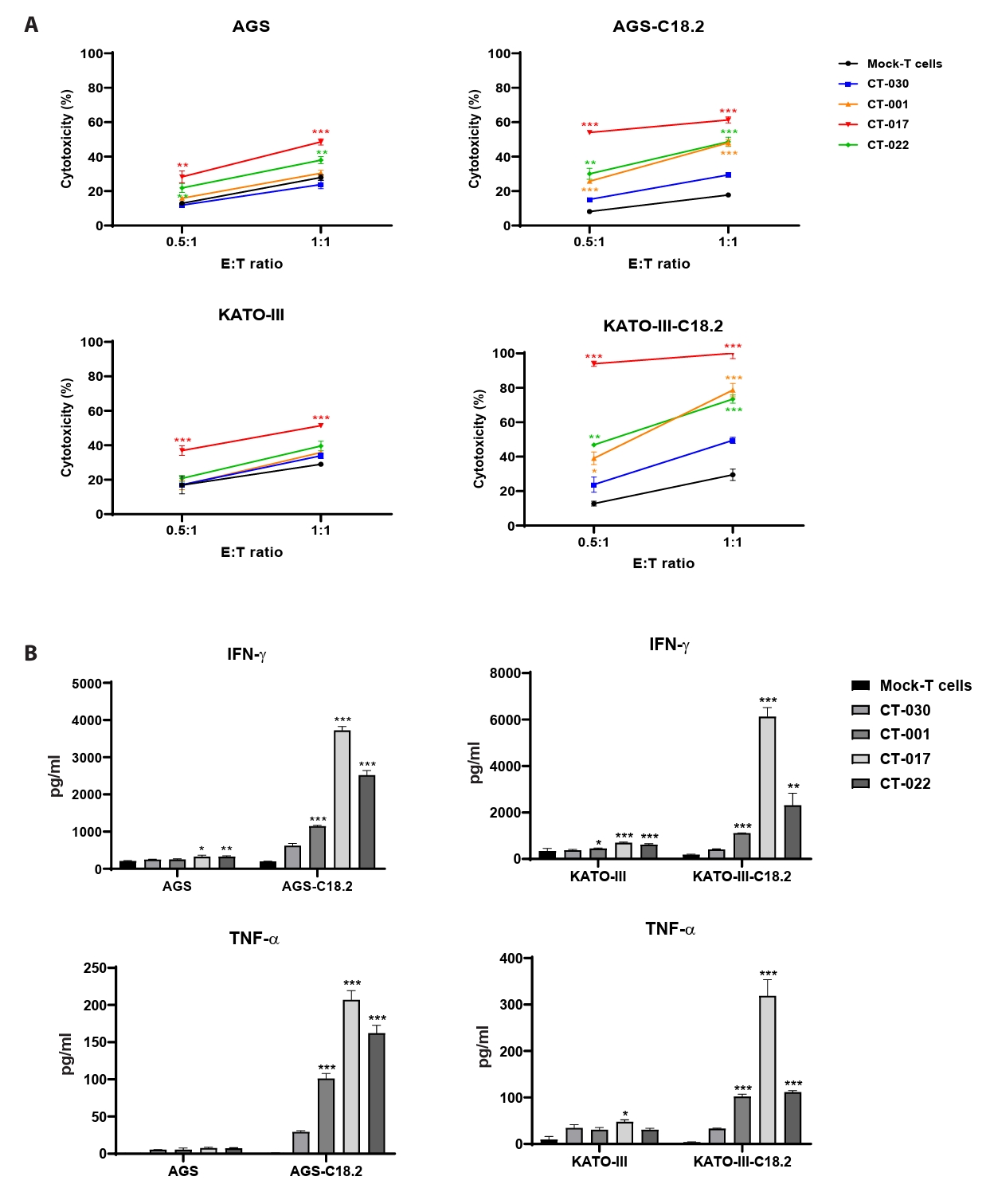

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

TOP

MSK

MSK

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article