ABSTRACT

- Two Gram-stain-negative, aerobic, non-motile, rod-shaped bacterial strains, designated IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, were isolated from surface seawater collected off Deokjeok Island and Jangbong Island, respectively, in the Yellow Sea. The two strains shared 100% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with each other but exhibited ≤ 96.2% similarity to validly published species of the genus Robiginitalea. Complete whole-genome sequences of IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T were 3.21 Mb and 3.30 Mb in size, with DNA G + C contents of 46.5% and 46.4%, respectively. Genome-based relatedness analyses revealed average nucleotide identity (ANI) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values of 90.7% and 42.9% between the two strains, which are well below the accepted species-level thresholds. Furthermore, ANI (≤ 70.2%) and dDDH (≤ 17.8%) values relative to type strains of Robiginitalea species supported the conclusion that strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T each represent novel species within the genus. Chemotaxonomic characterization showed that iso-C15:0, iso-C17:0 3-OH and iso-C15:1 G were the major fatty acids of both strains; menaquinone-6 (MK-6) was the sole isoprenoid quinone; and the major polar lipids comprised phosphatidylethanolamine, glycolipids, aminolipids, phospholipids, and other unidentified lipids. Based on phylogenetic, genomic, and phenotypic evidence, strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T are proposed as two novel species, Robiginitalea rubriflava sp. nov. and Robiginitalea insularis sp. nov., respectively. The type strains are IMCC43444T (= KCTC 102397T = JCM 37893T) and IMCC44478T (= KCTC 102398T = JCM 37894T).

-

Keywords: Robiginitalea rubriflava, Robiginitalea insularis, polyphasic taxonomy, marine bacteria, novel species, genome

Introduction

The genus Robiginitalea, belonging to the family Flavobacteriaceae within the class Flavobacteriia, was first proposed by Cho and Giovannoni (2004) based on seawater isolates from the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, and currently comprises six validly published species: R. biformata (the type species; Cho and Giovannoni, 2004), R. myxolifaciens (Manh et al., 2008), R. sediminis (Zhang et al., 2018), R. marina (Xuan et al., 2022), R. aurantiaca (Zhou et al., 2023), and R. aestuariiviva (Cao et al., 2023). The six currently recognized species of the genus Robiginitalea have been recovered from a broad array of marine environments, including open-ocean seawater, coastal sedimentary habitats, sea-cucumber aquaculture ponds, and tidal-flat sediments, reflecting the ecological versatility of the lineage.

The species of the genus Robiginitalea share several conserved phenotypic characteristics, as they are Gram-stain-negative, aerobic, and non-motile bacteria that characteristically produce pale red to orange pigments and grow optimally under mesophilic and moderately halophilic conditions typical of coastal marine ecosystems. Chemotaxonomically, the presence of menaquinone-6 (MK-6) as the predominant respiratory quinone, together with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) as a major identified polar lipid, in the genus Robiginitalea reflects a chemotaxonomic profile broadly shared among members of the family Flavobacteriaceae (Bernardet et al., 2002). Genomic features of the genus Robiginitalea also fall within a relatively narrow range, with genome sizes of 3.21–3.53 Mb and DNA G + C contents of 46.9–55.7 mol%. Notably, these comparatively high G + C values place the genus among the upper range within the family Flavobacteriaceae, most members of which typically exhibit substantially lower G + C contents of approximately 30–45 mol% (Gavriilidou et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2022). Morphological diversity within the genus is noteworthy, as species such as R. biformata, R. myxolifaciens, R. sediminis, and R. aestuariiviva exhibit pleomorphic transitions between rod-shaped and coccoid cells, whereas R. marina and R. aurantiaca maintain consistently rod-shaped morphology, suggesting potential ecological or genomic determinants underlying morphological stability.

Coastal waters of the Korean Peninsula are recognized as biologically dynamic systems that harbor a substantial reservoir of uncharacterized microbial lineages, and numerous novel bacterial taxa have indeed been intermittently isolated and described from these environments in recent years (Han et al., 2025; Kim et al., 2025; Lee et al., 2024; Tak et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). As part of our ongoing investigation into marine bacterial diversity, we characterized strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, which were isolated from coastal surface seawater off two islands in the Yellow Sea during a survey of prokaryotic diversity in island-associated marine habitats. Comprehensive analyses of their physiological, phylogenetic, chemotaxonomic, and genomic characteristics supported the conclusion that each of the two strains represents a novel species within the genus Robiginitalea.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture conditions

Strain IMCC43444T was isolated from coastal surface seawater collected at Deokjeok Island, Incheon, Republic of Korea (37.2211º N, 126.1126º E) in June 2022, and strain IMCC44478T was obtained from Jangbong Island, Incheon (37.5283º N, 126.3469º E) in June 2023. Serial dilutions of the seawater samples were spread onto marine agar 2216 (MA; BD Difco, USA), and colonies obtained after incubation at 25°C for 5 days were purified by three successive transfers. The purified isolates were maintained on MA and preserved as 10% (v/v) glycerol suspensions at −80℃. For comparative phenotypic analyses, the closely related type strains R. biformata KCTC 12146T (= HTCC2501T) and R. sediminis KCTC 52898T (= O458T) were obtained from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) and cultivated on MA at 25°C for 5 days.

Whole-genome sequencing and analysis

Approximately 50 mg (wet weight) of cells of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T harvested from MA plates was resuspended in DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research, USA) and shipped to MicrobesNG (UK) for sequencing. Whole-genome sequencing was carried out by MicrobesNG using a hybrid approach that combined Illumina and Oxford Nanopore platforms. Short-read libraries were generated with the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA) and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 2000 instrument to produce 250 bp paired-end reads. Long-read libraries were prepared using the SQK-RBK114.96 kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) and sequenced on a PromethION system equipped with a FLO-PRO114M flow cell. Hybrid genome assembly was generated with Hybracter v0.11.2 (Bouras et al., 2024). Genome completeness and contamination were assessed using CheckM2 v1.1.0 (Chklovski et al., 2023) with default parameters.

For comparative genomic analyses and assessment of genome relatedness, the genome assemblies of R. biformata HTCC2501T (accession no. CP001712), R. myxolifaciens DSM21019T (FOYQ00000000), R. sediminis O458T (NGNR00000000), R. marina 2V75T (JAMXIB000000000), R. aurantiaca M39T (JAUDUY000000000), and R. aestuariiviva M366T (JARPUQ000000000) were retrieved from the GenBank database. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) values were determined using JSpeciesWS (Richter et al., 2016), and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values were estimated with the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC 3.0) (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013). Genome-based phylogenetic relationships were inferred using GTDB-Tk v2.4.0 (Chaumeil et al., 2022) with the bacterial bac120 marker gene set from the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) release R226. The resulting concatenated alignment of 120 single-copy marker genes was analyzed under the maximum-likelihood framework using RAxML v8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2014). Functional genome annotation was performed with Prokka v1.14.6 (Seemann, 2014), after which predicted protein sequences were assigned to KEGG orthologs using BlastKOALA (Kanehisa et al., 2016), and metabolic pathway profiles were refined with kegg-pathway-completeness tool v1.3.0 (https://github.com/EBI-Metagenomics/kegg-pathways-completeness-tool).

16S rRNA gene-based phylogenetic analysis

Genomic DNA from strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T was extracted by suspending purified colonies in Tris-EDTA buffer, followed by multiple freeze–thaw cycles and mechanical disruption with glass beads. The resulting lysates were used directly as templates for PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene using the universal bacterial primers 27F and 1492R. PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen, Inc. (Korea) using the Sanger method with the sequencing primers 518F, 519R, 800R, and 926F. Since the genome-derived 16S rRNA gene sequences were identical to the PCR-amplified sequences, subsequent analyses were conducted using the genome-derived sequences (see ‘Results and Discussion’).

The 16S rRNA gene sequences were compared against the GenBank database using BLASTn, and pairwise similarity values were calculated with the EzBioCloud server (Chalita et al., 2024). For phylogenetic analyses, the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the two strains and those of related taxa were aligned with the SINA aligner (SILVA Incremental Aligner; v1.2.12) (Pruesse et al., 2012) and imported into the ARB software package (Ludwig et al., 2004). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018) using three algorithms: maximum-likelihood (ML) (Felsenstein, 1981) with the Tamura–Nei substitution model (Tamura and Nei, 1993), neighbor-joining (NJ) (Saitou and Nei, 1987), and minimum-evolution (ME) (Fitch, 1971), using evolutionary distances calculated with the Jukes–Cantor model (Jukes and Cantor, 1969). The robustness of tree topologies was evaluated by bootstrap analyses with 1,000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985).

Physiological and biochemical characterization

Cell morphology was examined by transmission electron microscopy (CM200, Philips, Netherlands) using a negative-staining procedure. Cells were suspended in 0.2 M cacodylate buffer, stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA), and mounted onto Formvar-coated copper grids (FCF300-CU; Ted Pella, USA). The Gram reaction was assessed using the KOH-based non-staining method (Powers, 1995). Catalase activity was tested by applying 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide, whereas oxidase activity was determined using 1% (w/v) Kovac’s reagent (bioMérieux, France). Carotenoid pigments were extracted with acetone, and absorption spectra were scanned over the range of 350–600 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Japan). Flexirubin-type pigments were examined using the KOH method (Fautz and Reichenbach, 1980) by applying a 20% (w/v) KOH solution to fresh colonies and resulting color changes were recorded. Motility was evaluated by inoculating cells into soft marine agar (0.5%, BD Difco, USA) and monitoring the outward dispersion of growth. Growth at various temperatures was examined on MA plates at 4°C and from 10 to 50°C at 5°C intervals. Salt requirements were determined on NaCl-free MA supplemented with NaCl to final concentrations of 0–4.0% (0.5% increments), 5%, 7.5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% (w/v). The pH range and optimum were assessed in marine broth (MB, BD Difco, USA) adjusted to pH 3.5–10.5 at 0.5-unit intervals using citrate, MES, MOPS, HEPES, Tris, and CHES buffers (all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Growth under these conditions was monitored by measuring OD600 with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV2600; Shimadzu, Japan). Anaerobic growth was evaluated using the GasPakTM EZ Anaerobe Pouch System with Indicator (BD Diagnostics, USA). Hydrolytic activities were examined on MA containing starch (1%, w/v), carboxymethyl cellulose (1%, w/v), chitin (1%, w/v), casein (3% skim milk, w/v), Tween 20 (1%, v/v), and Tween 80 (1%, v/v) (all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA). For casein-containing plates, skim milk solution and marine agar were autoclaved separately and aseptically mixed prior to plate preparation. DNA degradation was assessed using DNase Test Agar (BD Diagnostics, USA), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production was evaluated on Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) Agar (BD Difco, USA). Additional biochemical characteristics were determined using API 20NE and API ZYM kits (bioMérieux, France) and the GEN III MicroPlate system (Biolog, USA), with salinity adjusted to 2% NaCl.

Chemotaxonomic characterization

Fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) analysis was conducted using biomass from strains IMCC43444T, IMCC44478T, R. biformata HTCC2501T, and R. sediminis O458T grown on MA plates at 25°C for 5 days. Cellular fatty acids were converted to methyl esters and analyzed on an Agilent 7890 GC (Agilent Technologies, USA) using the Sherlock MIS (MIDI, USA) v6.1 with the TSBA6 database (Sasser, 1990). Polar lipids were extracted following the method of Minnikin et al. (1984) and separated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck, Germany). TLC plates were developed using chloroform/methanol/water (60:30:4, v/v) in the first dimension and chloroform/acetic acid/methanol/water (40:7.5:6:1.8, v/v) in the second dimension. Total polar lipids were visualized with molybdophosphoric acid, while specific lipid classes were detected using ninhydrin (aminolipids), molybdenum blue (phospholipids), α-naphthol (glycolipids), and Dragendorff’s reagent (phosphatidylcholine). Respiratory isoprenoid quinones were co-extracted with polar lipids and analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance TLC (HPTLC) on RP-18 F254 plates (Merck, Germany) according to Collins and Jones (1981). Quinone types were identified by comparing their chromatographic mobilities with those of type strain of the type species, R. biformata HTCC2501T.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T have been deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases under accession numbers PX239447 and PX239448, respectively. The complete genome sequences of IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T are available under accession numbers CP199309 and CP199296, respectively.

Results and Discussion

16S rRNA gene-based phylogeny

The PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains IMCC43444T (1,453 bp) and IMCC44478T (1,442 bp) were completely identical to their corresponding genome-derived sequences (1,524 and 1,525 bp, respectively). Both strains contained two copies of the 16S rRNA gene, which were identical within each genome, and thus subsequent 16S rRNA gene analyses were carried out using the genome-derived sequences. Pairwise sequence analysis revealed that strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T shared 100% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity with each other. Because this value clearly exceeds the commonly accepted 98.7% species-level threshold (Riesco and Trujillo, 2024), additional genome-based analyses were necessary to determine whether the two strains represent a single species or two distinct species.

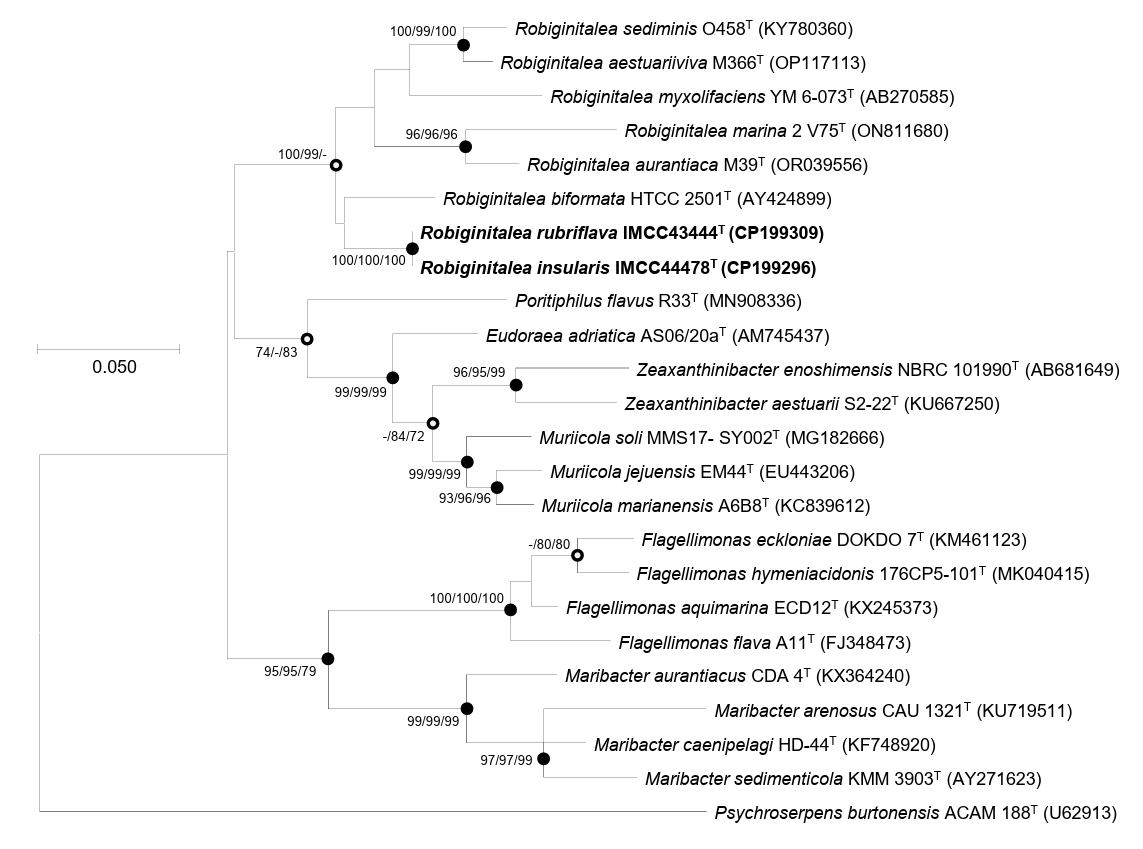

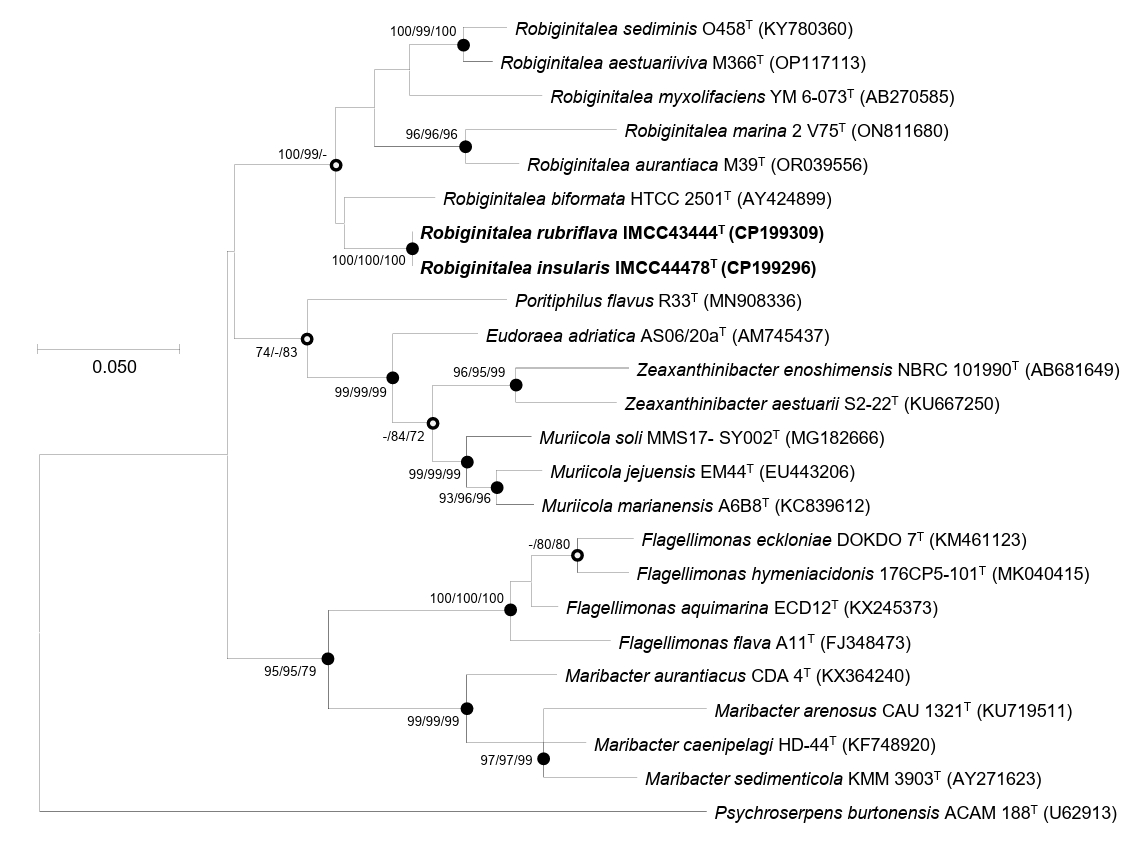

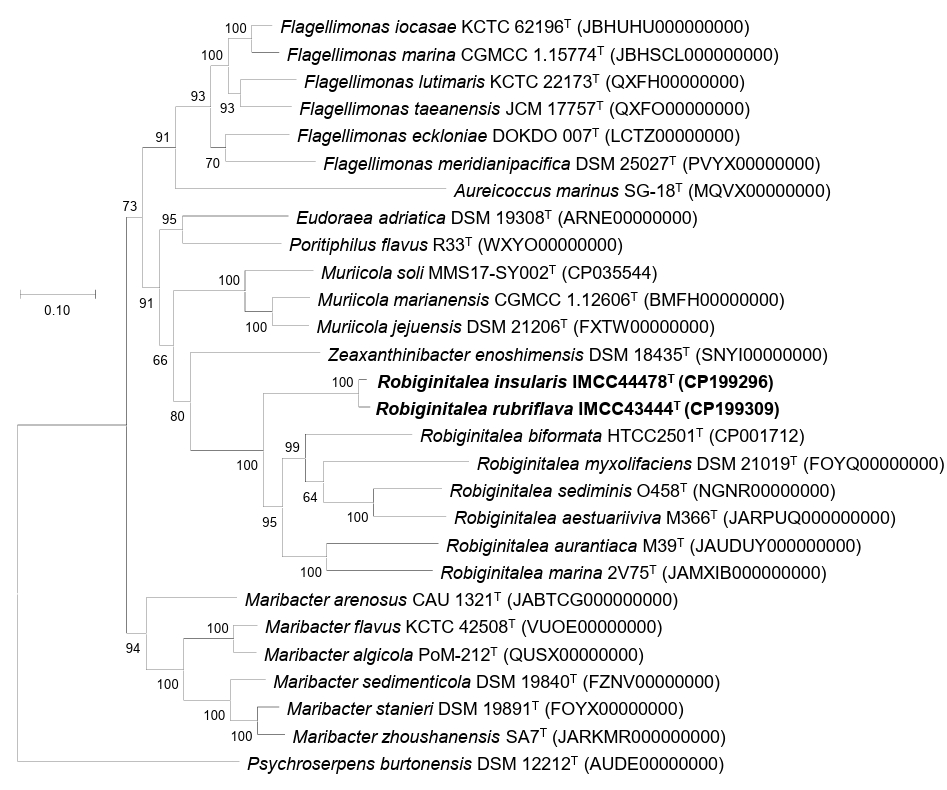

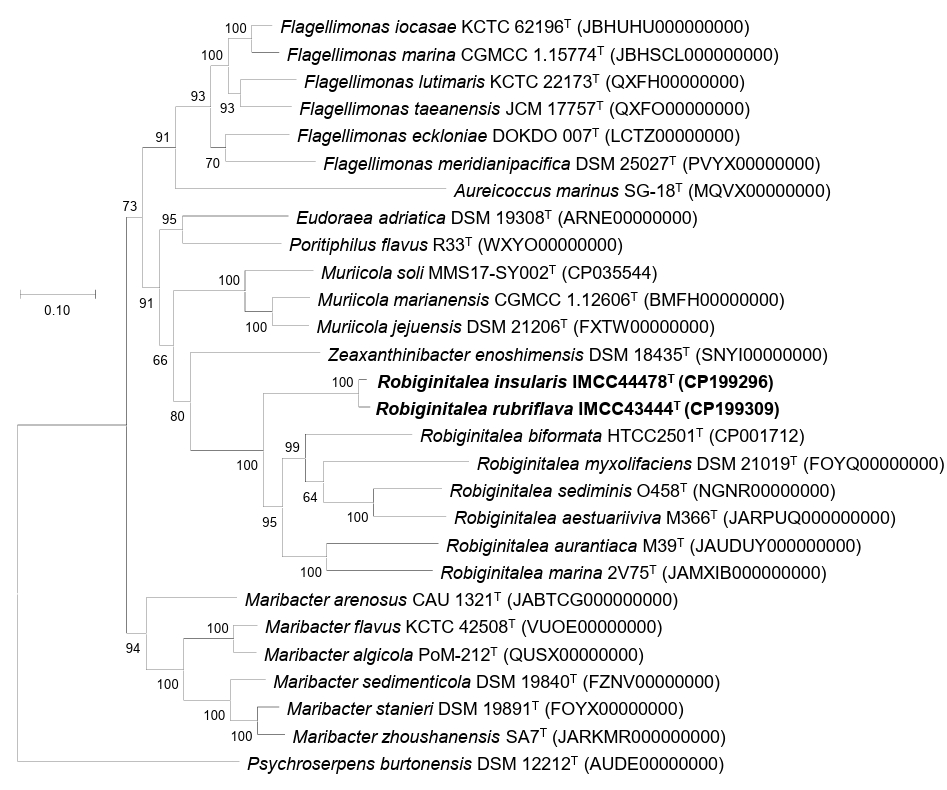

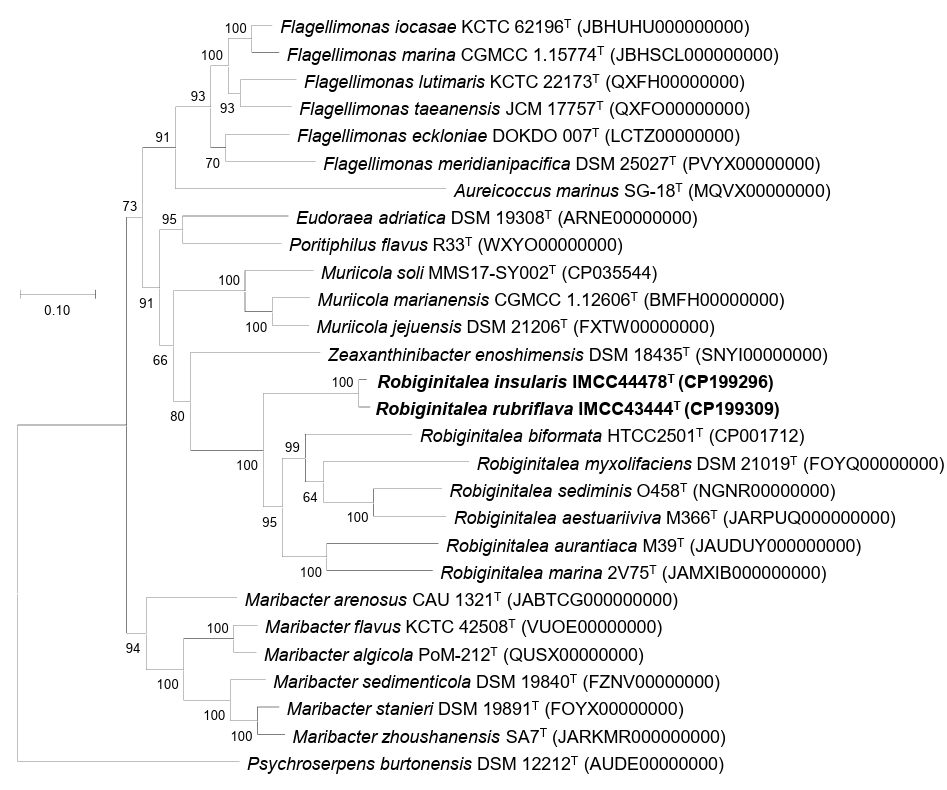

Comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses and their phylogenetic relationships suggested that strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T are affiliated with the genus Robiginitalea. The two strains exhibited highest similarity to R. biformata HTCC2501T (96.2%), followed by R. sediminis O458T (95.4%), R. aurantiaca M39T (95.2%), R. aestuariiviva M366T (95.1%), R. myxolifaciens DSM 21019T (94.1%), and R. marina 2V75T (94.1%). These similarity values, all below the 98.7% cutoff, clearly indicated that the strains represent a lineage distinct from previously characterized members of the genus Robiginitalea. Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences placed strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T within the genus Robiginitalea, where they formed a distinct and strongly supported clade (Fig. 1). The two strains clustered together on a distinct branch as a sister group to R. biformata HTCC2501T, consistent with their highest pairwise similarity to this species (96.2%), and were clearly separated from the six validly published Robiginitalea species, supporting their placement as a coherent lineage within the genus.

Genome characteristics and phylogenomic analysis

The complete genomes of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T were each assembled into a single circular chromosome of 3,209,214 bp and 3,300,668 bp, with G + C contents of 46.5% and 46.4%, respectively. Genome quality assessed using CheckM2 indicated completeness and contamination values of 100% and 0.2% for IMCC43444T and 99.9% and 0.1% for IMCC44478T, confirming high-quality assemblies. Genome annotation identified 2,887 and 2,968 protein-coding sequences, 39 and 40 tRNA genes, and six rRNA genes in IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, respectively. The two strains notably possess two copies of the rrn operon, whereas all previously described Robiginitalea species contain only a single copy (Table S1). A summary of the general genomic features of the two strains and the six type strains of validly published Robiginitalea species is presented in Table S1.

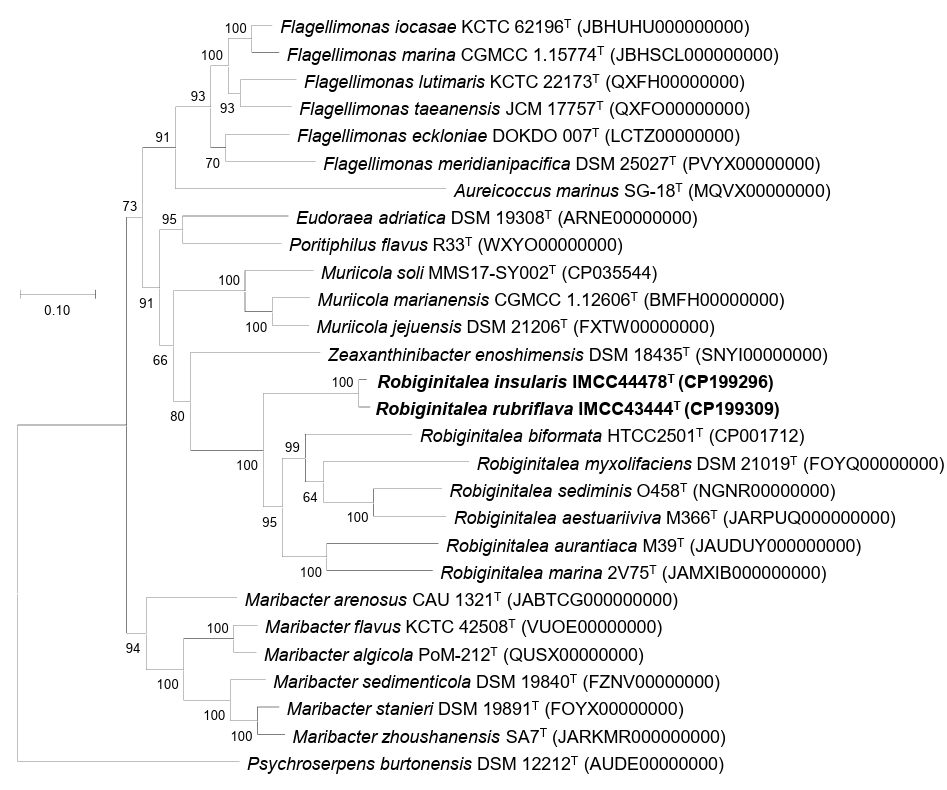

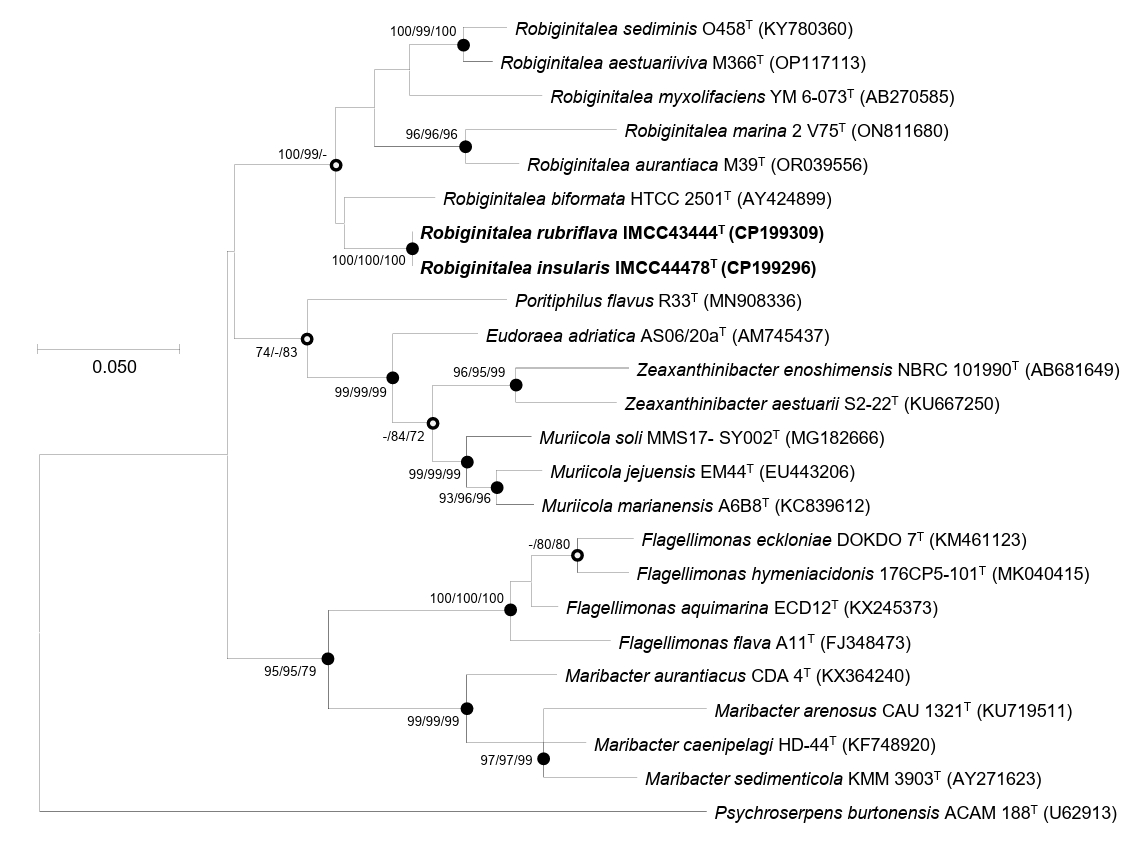

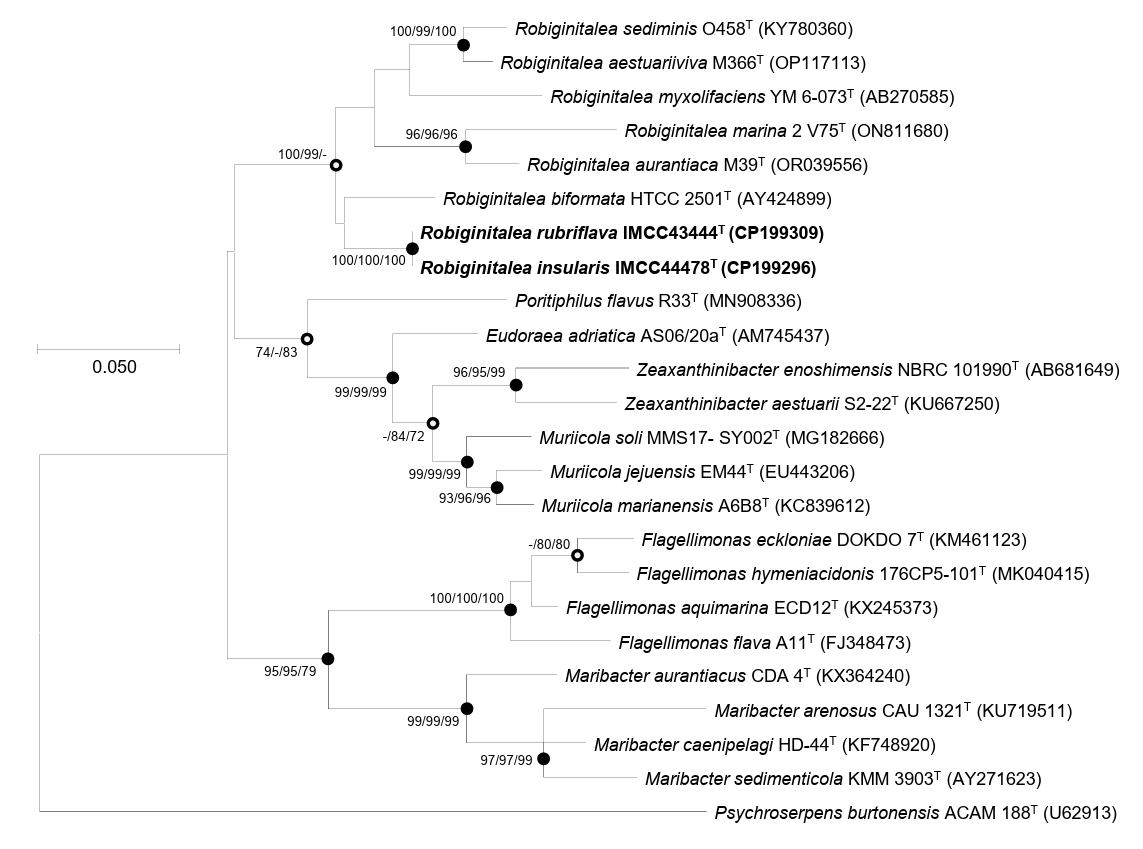

Overall genome relatedness among strains IMCC43444T, IMCC44478T, and the validly published Robiginitalea species was assessed using ANI and dDDH values. The ANI and dDDH values between IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T were 90.7% and 42.9%, respectively, both below the accepted species-level thresholds of 95–96% ANI and 70% dDDH (Riesco and Trujillo, 2024). These results indicate that the two strains represent distinct novel species of the genus Robiginitalea. Pairwise comparisons with six validly published Robiginitalea species yielded ANI values of 69.1–70.2% and dDDH values of 16.2–17.8% for both strains, further supporting their delineation as two separate species. Genome-based phylogenetic reconstruction consistently placed IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T in a distinct, well-supported clade within Robiginitalea, confirming their affiliation with the genus (Fig. 2).

The high-quality genomes of the two strains were subjected to functional annotation. The completeness of major metabolic pathways in IMCC43444T, IMCC44478T, and six Robiginitalea species is summarized in Fig. S1. All genomes encoded the complete set of central carbon metabolic pathways, including glycolysis (Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway), the tricarboxylic acid cycle, gluconeogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway, consistent with a heterotrophic lifestyle. Genes associated with a complete oxidative phosphorylation system were also identified, supporting their capacity for aerobic respiration. Notably, IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, as well as other Robiginitalea genomes, harbor genes encoding a high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome c oxida in addition to the canonical prokaryotic cytochrome c oxidase, suggesting potential adaptation to low-oxygen or microaerophilic conditions (Zhang et al., 2023). With respect to nitrogen and sulfur metabolism, none of the genomes examined encoded pathways for sulfur oxidation, sulfur reduction, nitrification, or canonical denitrification, indicating that members of the genus are aerobic chemoorganoheterotrophs. However, the gene encoding nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ; K00376) was consistently detected in five Robiginitalea species but was absent from IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T. These findings suggest that some members of the genus may function as partial denitrifiers capable of reducing nitrous oxide to dinitrogen despite lacking upstream denitrification steps (Pold et al., 2025). Overall, the functional profiles of the two strains resemble those of other Robiginitalea species, indicating that they are strictly aerobic chemoorganoheterotrophs. Although strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T were isolated from geographically proximate islands, they exhibit notable genomic and phenotypic divergence, suggesting fine-scale micro-niche partitioning within spatially heterogeneous marine habitats.

Phenotypic characteristics

Transmission electron microscopy revealed that cells of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T were rod-shaped, measuring approximately 0.3–0.7 × 1.3–3.8 µm and 0.5–0.6 × 1.9–2.2 µm, respectively (Fig. S2). No flagella were observed, consistent with the absence of flagellar biosynthesis genes in their genomes. The physiological and biochemical characteristics of IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, along with those of two closely related Robiginitalea species including the type species of the genus, are summarized in Table 1 and in the species protologues. The two strains exhibited generally similar physiological profiles, including comparable growth ranges, positive oxidase and catalase activities, and the ability to degrade high-molecular-weight substrates, but differed in a few enzyme activities and carbon source oxidation patterns (Table 1). In addition, strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T could be differentiated from the two related Robiginitalea species based on differences in growth characteristics, casein degradation, selected enzymatic activities such as gelatinase, and carbon source oxidation profiles.

The fatty acid compositions of IMCC43444T, IMCC44478T, and two related type strains of the genus Robiginitalea are summarized in Table 2. All four strains exhibited similar fatty acid profiles, characterized by the predominance of iso-C15:0, iso-C17:0 3-OH, and iso-C15:1 G, consistent with their affiliation within the same genus. The two strains shared several major fatty acids present at abundances greater than 10%, including iso-C15:0 (29.3% and 27.2% in IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, respectively), iso-C17:0 3-OH (13.0% and 17.3%), and iso-C15:1 G (15.1% and 20.5%). Despite these similarities, notable quantitative differences were observed, particularly in anteiso-C15:0, which accounted for 14.6% in IMCC43444T but only 6.7% in IMCC44478T. These differences, together with variations in selected unsaturated fatty acids, provide phenotypic markers that distinguish the two strains from each other as well as from previously described Robiginitalea species.

Both strains contained menaquinone-6 (MK-6) as the sole respiratory quinone, consistent with members of the genus Robiginitalea. The major polar lipids of IMCC43444T consisted of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), two unidentified glycolipids (GL), three unidentified aminolipids (AL), three unidentified phospholipids (PL), and five unidentified lipids (Fig. S3). A similar polar lipid profile was observed for IMCC44478T, which contained PE, two GL, three AL, two PL, and two unidentified lipids. The occurrence of PE, GL, and AL as diagnostic lipid classes is consistent with polar lipid patterns previously reported for members of the genus Robiginitalea. Taken together, the fatty acid compositions, respiratory quinone type, and polar lipid profiles of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T provide congruent chemotaxonomic evidence supporting their assignment to the genus Robiginitalea.

Taxonomic conclusion

Based on 16S rRNA gene phylogeny, overall genome relatedness indices, and comprehensive physiological and chemotaxonomic characteristics, strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T are unambiguously assigned to the genus Robiginitalea. The two strains exhibited ANI and dDDH values that were well below the accepted species-level thresholds and showed low genomic similarity to all validly published Robiginitalea species. These genomic distinctions, together with clear differences in physiological properties, fatty acid composition, and polar lipid patterns, provide consistent evidence that IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T represent two independent and previously undescribed species within the genus Robiginitalea. Accordingly, the names Robiginitalea rubriflava sp. nov. and Robiginitalea insularis sp. nov. are proposed for IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, respectively.

Description of Robiginitalea rubriflava sp. nov.

Robiginitalea rubriflava (ru.bri.fla’va. L. adj. ruber, red; L. adj. flavus, yellow; N.L. fem. adj. rubriflava, reddish-yellow, referring to the colony pigmentation).

Cells are Gram-stain-negative, strictly aerobic, and non-motile rods, measuring 0.3–0.7 µm in width and 1.3–3.8 µm in length. Colonies on marine agar are reddish-yellow, circular, and convex. Carotenoid pigments are present. Flexirubin-type pigments are not detected. Growth occurs at 15–35℃ (optimum, 30℃), pH 6.5–7.5 (optimum, pH 7.0), and in the presence of 0.5–5.0% (w/v) NaCl (optimum, 3.0%). Oxidase and catalase activities are positive. Hydrolyzes Tween 20 and Tween 80, but does not hydrolyze casein, colloidal chitin, DNA, starch, or CM-cellulose. In API 20NE tests, esculin hydrolysis, gelatinase, and β-galactosidase are positive, but nitrate reduction, indole production, glucose fermentation, arginine dihydrolase, and urease activities are negative. In API ZYM tests, alkaline phosphatase, esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), lipase (C14), leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, acid phosphatase, naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, α-galactosidase, α-glucosidase, and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activities are positive, whereas β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, α-mannosidase, and α-fucosidase activities are negative. In the GEN III MicroPlate (Biolog), the following carbon sources are oxidized: D-trehalose, gentiobiose, D-turanose, α-D-glucose, glucuronamide, α-ketoglutaric acid, L-malic acid, bromo-succinic acid, and acetoacetic acid. The predominant fatty acids are iso-C15:0, anteiso-C15:0, iso-C17:0 3-OH, and iso-C15:1 G. The major respiratory quinone is menaquinone-6 (MK-6). The polar lipid profile comprises phosphatidylethanolamine, two unidentified glycolipids, three unidentified aminolipids, three unidentified phospholipids, and five unidentified lipids.

The type strain is IMCC43444T (= KCTC 102397T = JCM 37893T), isolated from surface seawater off Deokjeok Island, Republic of Korea. The genome size of the type strain is 3,209,214 bp, with a DNA G + C content of 46.5%. The GenBank accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequence and genome sequence are PX239447 and CP199309, respectively.

Description of Robiginitalea insularis sp. nov.

Robiginitalea insularis (in.su.la’ris. L. fem. adj. insularis, island-dwelling, referring to the isolation of the type strain from coastal waters surrounding Korean islands.).

Cells are Gram-stain-negative, strictly aerobic, and non-motile rods, measuring 0.5–0.6 µm in width and 1.9–2.2 µm in length. Colonies grown on marine agar are reddish-yellow, circular, and convex. Carotenoid pigments are present. Flexirubin-type pigments are not detected. Growth occurs at 15–40℃ (optimum, 35℃), pH 6.5–7.5 (optimum, pH 7.0), and in the presence of 0.5–5.0% (w/v) NaCl (optimum, 2.5%). Oxidase and catalase activities are positive. Hydrolyzes Tween 20 and Tween 80, but does not hydrolyze casein, colloidal chitin, DNA, starch, or CM-cellulose. In API 20NE tests, esculin hydrolysis, gelatinase, and β-galactosidase are positive, but nitrate reduction, indole production, glucose fermentation, arginine dihydrolase, and urease activities are negative. In API ZYM tests, alkaline phosphatase, esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), lipase (C14), leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, acid phosphatase, naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, α-glucosidase, and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activities are positive, whereas α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, α-mannosidase, and α-fucosidase activities are negative. In the GEN III MicroPlate (Biolog), the following carbon sources are oxidized: dextrin, D-trehalose, gentiobiose, D-turanose, α-D-glucose, D-fructose-6-phosphate, glucuronamide, L-malic acid, bromo-succinic acid, and acetoacetic acid. The predominant fatty acids are iso-C15:0, iso-C17:0 3-OH, and iso-C15:1 G. The major respiratory quinone is menaquinone-6 (MK-6). The polar lipid profile comprises phosphatidylethanolamine, two unidentified glycolipids, three unidentified aminolipids, two unidentified phospholipids, and two unidentified lipids.

The type strain is IMCC44478T (= KCTC 102398T = JCM 37894T), isolated from coastal seawater off Jangbong Island, Republic of Korea. The genome size of the type strain is 3,300,668 bp, with a DNA G + C content of 46.4%. The GenBank accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequence and genome sequence are PX239448 and CP199296, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the research grant “Survey of island-coastal indigenous organisms (Prokaryotes)” from Honam National Institute of Biological Resources (HNIBR) in Korea and by the High Seas Bioresources Program of the Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (KIMST-20210646).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.71150/jm.2512009.

Table S2.

Carbon source oxidation patterns (GENⅢ MicroPlate) of IMCC43444T, IMCC44478T, Robiginitalea biformata KCTC 12146T, and Robiginitalea sediminis KCTC 52898T

jm-2512009-Supplementary-Table-S2.pdf

Fig. S1.

Genomic potential of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T. Heatmaps depict the completeness of key metabolic pathways involved in central carbon metabolism, nitrogen metabolism, sulfur metabolism, and carbon fixation across these strains and the related type strains of the genus Robiginitalea. Numbers in parentheses indicate the corresponding KEGG module accession identifiers.

jm-2512009-Supplementary-Fig-S1.pdf

Fig. S2.

Transmission electron micrographs of cells of strains IMCC43444T (A) and IMCC44478T (B) after negative staining with 1.0% (w/v) uranyl acetate. Cells were grown on marine agar at 25°C for 5 days. Bar, 0.5 μm.

jm-2512009-Supplementary-Fig-S2.pdf

Fig. S3.

Two-dimensional thin layer chromatograph of polar lipids of strains IMCC43444T (A) and IMCC44478T (B). PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; GL, unidentified glycolipid; AL, unidentified aminolipid; PL, unidentified phospholipid; L, unidentified lipid.

jm-2512009-Supplementary-Fig-S3.pdf

Fig. 1.Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the phylogenetic placement of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T. Bootstrap support values (≥ 70%) from the maximum-likelihood, neighbor-joining, and minimum-evolution methods (in that order) are shown at the corresponding nodes. Closed circles indicate nodes recovered by all three tree-building methods, whereas open circles denote nodes supported by two of the three methods. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T used for tree reconstruction were derived from the complete genome sequences. Scale bar, nucleotide substitutions per site.

Fig. 2.Maximum-likelihood phylogenomic tree showing the relationships between strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T and their related type strains. The tree was reconstructed using GTDB-Tk (bac120 marker set) and RAxML based on the concatenated amino acid sequences of 120 conserved single-copy marker genes. Bootstrap support values (≥ 70%) are shown at the nodes. Scale bar, substitutions per amino acid position.

Table 1.

Differential phenotypic characteristics of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T, and closely related type strains of the genus Robiginitalea

Strains: 1, IMCC43444T; 2, IMCC44478T; 3, R. biformata KCTC 12146T; 4, R. sediminis KCTC 52898T. Data were obtained from this study. All strains positive for degradation of Tween 20 and Tween 80, and enzyme activities for catalase, oxidase, esculin hydrolysis (β-glucosidase), PNPG (β-galactosidase), alkaline phosphatase, esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), lipase (C14), leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, acid phosphatase, and naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase. Detailed carbon source oxidation pattern is summarized in Table S2. +, Positive; ‒, negative.

|

Characteristics |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Colony color

|

reddish-yellow |

reddish-yellow |

rust-colored |

orange |

|

Growth at

|

|

|

|

|

|

Temperature range (optimum, ºC) |

15–35 (30) |

15–40 (35) |

10–45 (30) |

15–45 (35) |

|

pH range (optimum) |

6.5–7.5 (7.0) |

6.5–7.5 (7.0) |

6.0–9.0 (8.0) |

6.5–8.5 (7.5) |

|

NaCl range (optimum, %) |

0.5–5.0 (3.0) |

0.5–5.0 (2.5) |

0.25–10.0 (2.5) |

1.0–6.0 (2.0) |

|

Hydrolysis of:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Casein |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

|

API 20NE

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gelatinase |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

API ZYM

|

|

|

|

|

|

α-Galactosidase |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

|

β-Galactosidase, α-mannosidase |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

|

β-Glucuronidase |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

|

β-Glucosidase |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

|

GEN III

|

|

|

|

|

|

D-Maltose, D-cellobiose, sucrose, β-methyl-D-glucoside |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

|

L-Galactonic acid lactone, |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

|

L-histidine, |

|

D-Glucuronic acid |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

|

Dextrin, D-fructose-6-phosphate |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

D-Trehalose |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

α-Ketoglutaric acid |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

Table 2.Cellular fatty acid compositions of strains IMCC43444T and IMCC44478T and the closely related type strains of the genus Robiginitalea

Strains: 1, IMCC43444T; 2, IMCC44478T; 3, R. biformata KCTC 12146T; 4, R. sediminis KCTC 52898T. Data were obtained from this study. All strains were cultured under identical conditions. Fatty acids comprising < 0.5% of the total fatty acid content in all species were omitted. ‒, Not detected; Tr, traces (< 0.5%). Major fatty acids (> 10%) are shown in bold.

|

Fatty acid (%) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Saturated

|

|

|

|

|

|

C16:0

|

1.1 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.4 |

|

Branched

|

|

|

|

|

|

iso-C13:0

|

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

|

iso-C14:0

|

1.2 |

0.7 |

– |

1.4 |

|

iso-C15:0

|

29.3

|

27.2

|

22.1

|

23.2

|

|

iso-C16:0

|

3.8 |

3.6 |

0.6 |

1.6 |

|

iso-C17:0

|

Tr |

0.9 |

Tr |

Tr |

|

anteiso-C15:0

|

14.6

|

6.7 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

|

Hydroxy

|

|

|

|

|

|

iso-C15:0 3-OH |

4.2 |

4.2 |

6.4 |

5.5 |

|

iso-C16:0 3-OH |

3.4 |

3.7 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

|

iso-C17:0 3-OH |

13.0

|

17.3

|

25.4

|

21.0

|

|

C15:0 2-OH |

1.7 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

|

C17:0 2-OH |

2.5 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

|

C15:0 3-OH |

Tr |

Tr |

0.7 |

0.9 |

|

C17:0 3-OH |

Tr |

Tr |

0.5 |

0.7 |

|

C16:0 3-OH |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.7 |

1.3 |

|

Unsaturated

|

|

|

|

|

|

iso-C15:1 G |

15.1

|

20.5

|

21.2

|

23.5

|

|

anteiso-C15:1 A |

1.7 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

|

C16:1 iso G |

0.5 |

0.6 |

– |

Tr |

|

C13:1 at position 12–13 |

Tr |

Tr |

Tr |

0.5 |

|

C15:1 ω6c |

Tr |

– |

0.6 |

– |

|

C17:1 ω6c |

Tr |

Tr |

0.9 |

– |

|

Summed feature

|

|

|

|

|

|

Summed feature 3*

|

1.8 |

2.5 |

6.2 |

5.8 |

|

Summed feature 9*

|

1.1 |

1.6 |

1.0 |

– |

References

- Bernardet JF, Nakagawa Y, Holmes B; Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of Flavobacterium and Cytophaga-Like Bacteria of the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes. 2002. Proposed minimal standards for describing new taxa of the family Flavobacteriaceae and emended description of the family. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 52: 1049–1070. ArticlePubMed

- Bouras G, Page AJ, Watson M. 2024. Hybracter: enabling scalable, automated, complete and accurate bacterial genome assemblies. Microb Genom. 10: 001244.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Cao K, Gao JW, Zhang WW, Wang YR, Su Y, et al. 2023. Robiginitalea aestuariiviva sp. nov., isolated from sediment of a tidal flat located in Zhejiang, PR China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 73: 006170.ArticlePubMed

- Chalita M, Kim YO, Park S, Oh HS, Cho JH, et al. 2024. EzBioCloud: a genome-driven database and platform for microbiome identification and discovery. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 74: 006421.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Chaumeil PA, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. 2022. GTDB-Tk v2: memory friendly classification with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics. 38: 5315–5316. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Chklovski A, Parks DH, Woodcroft BJ, Tyson GW. 2023. CheckM2: a rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat Methods. 20: 1203–1212. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Cho JC, Giovannoni SJ. 2004. Robiginitalea biformata gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel marine bacterium in the family Flavobacteriaceae with a higher G+C content. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 54: 1101–1106. ArticlePubMed

- Collins MD, Jones D. 1981. Distribution of isoprenoid quinone structural types in bacteria and their taxonomic implications. Microbiol Rev. 45: 316–354. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Fautz E, Reichenbach H. 1980. Simple test for flexirubin-type pigments. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 8: 87–91. Article

- Felsenstein J. 1981. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum-likelihood approach. J Mol Evol. 17: 368–376. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 39: 783–791. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Fitch WM. 1971. Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specific tree topology. Syst Zool. 20: 406–416. Article

- Gavriilidou A, Gutleben J, Versluis D, Forgiarini F, van Passel MW, et al. 2020. Comparative genomic analysis of Flavobacteriaceae: insights into carbohydrate metabolism, gliding motility and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. BMC Genomics. 21: 569.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Han J, Lim Y, Kim M, Cho JC. 2025. Rubrivirga aquatilis sp. nov. and Rubrivirga halophila sp. nov., isolated from Korean coastal surface seawater. J Microbiol. 63: e2504017. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules. In Munro HN. (ed.), Mammalian Protein Metabolism, vol. 3, pp. 21–132. Academic Press. Article

- Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. 2016. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol. 428: 726–731. ArticlePubMed

- Kim JM, Baek W, Choi BJ, Bayburt H, Lee JK, et al. 2025. Phycobium rhodophyticola gen. nov., sp. nov. and Aliiphycobium algicola gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from the phycosphere of marine red algae. J Microbiol. 63: e2503014. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Kim SJ, Kim YS, Kim SE, Jung HK, Park J, et al. 2022. Rasiella rasia gen. nov., sp. nov. within the family Flavobacteriaceae isolated from seawater recirculating aquaculture system. J Microbiol. 60: 1070–1076. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35: 1547–1549. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Lee J, Song SH, Moon K, Lee N, Ryu S, et al. 2024. Thalassotalea aquiviva sp. nov. and Thalassotalea maritima sp. nov., isolated from seawater of the coast in South Korea. J Microbiol. 62: 1099–1111. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 1363–1371. ArticlePubMedPMC

- Manh HD, Matsuo Y, Katsuta A, Matsuda S, Shizuri Y, et al. 2008. Robiginitalea myxolifaciens sp. nov., a novel myxol-producing bacterium isolated from marine sediment, and emended description of the genus Robiginitalea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 58: 1660–1664. ArticlePubMed

- Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Göker M. 2013. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 14: 60.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Minnikin DE, O’Donnell AG, Goodfellow M, Alderson G, Athalye M, et al. 1984. An integrated procedure for the extraction of bacterial isoprenoid quinones and polar lipids. J Microbiol Methods. 2: 233–241. Article

- Pold G, Saghaï A, Jones CM, Hallin S. 2025. Denitrification is a community trait with partial pathways dominating across microbial genomes and biomes. Nat Commun. 16: 9495.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Powers EM. 1995. Efficacy of the Ryu nonstaining KOH technique for rapidly determining gram reactions of food-borne and waterborne bacteria and yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 61: 3756–3758. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Pruesse E, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. 2012. SINA: accurate high-throughput multiple sequence alignment of ribosomal RNA genes. Bioinformatics. 28: 1823–1829. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R, Glöckner FO, Peplies J. 2016. JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics. 32: 929–931. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Riesco R, Trujillo ME. 2024. Update on the proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 74: 006300.ArticlePubMedPMC

- Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 4: 406–425. ArticlePubMed

- Sasser M. 1990. Identification of bacteria by gas chromatography of cellular fatty acids. MIDI technical note 101. MIDI Inc.

- Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 30: 2068–2069. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30: 1312–1313. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- Tak H, Park MS, Cho H, Lim Y, Cho JC. 2024. Congregibacter variabilis sp. nov. and Congregibacter brevis sp. nov. within the OM60/NOR5 clade, isolated from seawater, and emended description of the genus Congregibacter. J Microbiol. 62: 739–748. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Tamura K, Nei M. 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 10: 512–526. ArticlePubMed

- Xuan XQ, Mao RY, Yu WX, An J, Du ZJ, et al. 2022. Robiginitalea marina sp. nov., isolated from coastal sediment. Arch Microbiol. 204: 644.ArticlePubMedPDF

- Yang SH, Park MJ, Oh HM, Park YJ, Kwon KK. 2024. Flavivirga spongiicola sp. nov. and Flavivirga abyssicola sp. nov., isolated from marine environments. J Microbiol. 62: 11–19. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Zhang L, Dong T, Yang J, Hao S, Sun Z, et al. 2023. Anammox coupled with photocatalyst for enhanced nitrogen removal and the activated aerobic respiration of anammox bacteria based on cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase. Environ Sci Technol. 57: 17910–17919. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Zhang J, Han JR, Chen GJ, Du ZJ. 2018. Robiginitalea sediminis sp. nov., isolated from a sea cucumber culture pond. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 111: 905–911. ArticlePubMedPDF

- Zhou ZY, An J, Jia YW, Xuan XQ, Du ZJ. 2023. Robiginitalea aurantiaca sp. nov. and Algoriphagus sediminis sp. nov., isolated from coastal sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 73: 006155.Article

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article

MSK

MSK